|

|

HOME PAGE AND INDEX

HOME PAGE AND INDEXDr Bruce E Osborne

Tower House

KT20 5QY

United Kingdom

This book has been made available on-line in January 2010. Click on the chapters below to view the contents. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, computer scanning, recording or by any information and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher - except reasonable brief excerpts (up to 200 words) for publicity or academic research purposes as long as accompanying credit is given to author, title and source of book.

illustration 0.1. Cover - The Old Wells 1662 by Schellinks.

ISBN 0 9536711 8 6

Publication date - 2010

Publisher - SPAS Research Fellowship - see www.thespas.co.uk for contact details.

Biographical details: Click here for details of author Dr Bruce E Osborne.

Biographical details: Click here for details of author Dr Bruce E Osborne.A dose of Epsom Salts

For one hundred years they flocked to Epsom,

the visitor's craving was to purge.

The demise was rumoured on a deception,

can the sufferer mistake that fulfilled urge?

0.2. Proprietary packs of Epsom Salts

the visitor's craving was to purge.

The demise was rumoured on a deception,

can the sufferer mistake that fulfilled urge?

0.2. Proprietary packs of Epsom Salts

Chapters (click button to view)

1. The Waters of Ewell (up to 1700): Celtic, Roman and Medieval Ewell and Ewell springs.

1. The Waters of Ewell (up to 1700): Celtic, Roman and Medieval Ewell and Ewell springs.

2. Nonsuch - a Renaissance Balnea: Renaissance medicine, Henry VIII, Nonsuch Palace, Ewell springs, healing art and balnea, Elizabeth's bath.

2. Nonsuch - a Renaissance Balnea: Renaissance medicine, Henry VIII, Nonsuch Palace, Ewell springs, healing art and balnea, Elizabeth's bath.

1. The Waters of Ewell (up to 1700): Celtic, Roman and Medieval Ewell and Ewell springs.

1. The Waters of Ewell (up to 1700): Celtic, Roman and Medieval Ewell and Ewell springs.  2. Nonsuch - a Renaissance Balnea: Renaissance medicine, Henry VIII, Nonsuch Palace, Ewell springs, healing art and balnea, Elizabeth's bath.

2. Nonsuch - a Renaissance Balnea: Renaissance medicine, Henry VIII, Nonsuch Palace, Ewell springs, healing art and balnea, Elizabeth's bath.

Addendum to 2 (dated 2014). Recognition of the Earliest English Renaissance Grotto.

3. Inspiration for Epsom Spa (1550 - 1660): Spa in the Ardennes, Epsom Wells, the discovery, Lord North, early popularity and visitors, the Interregnum (1649-1659).

3. Inspiration for Epsom Spa (1550 - 1660): Spa in the Ardennes, Epsom Wells, the discovery, Lord North, early popularity and visitors, the Interregnum (1649-1659).  4. Flourishing spa (1660-1690): developments, visitors, reputation, demise of Nonsuch, Appendix: News from Epsom.

4. Flourishing spa (1660-1690): developments, visitors, reputation, demise of Nonsuch, Appendix: News from Epsom.  5. Seventeenth century mineralisation of the wells: problems at The Wells, solutions etc., scientific advance, Nehemiah Grew and Epsom Salts.

5. Seventeenth century mineralisation of the wells: problems at The Wells, solutions etc., scientific advance, Nehemiah Grew and Epsom Salts.  6. An Era of Expansion (1690-1712): Livingstone, the New Wells, further town development, visitors, Old Wells improved.

6. An Era of Expansion (1690-1712): Livingstone, the New Wells, further town development, visitors, Old Wells improved.  7. The Zenith of Epsom Spa (1712-1750): new treatments, artificial salts, closing the Old Wells, Livingstone's death, amusements, evidence of longevity of spa.

7. The Zenith of Epsom Spa (1712-1750): new treatments, artificial salts, closing the Old Wells, Livingstone's death, amusements, evidence of longevity of spa.  8. Recriminations and decline (1750-1780): efforts to resurrect the spa, spurious claims, medical profession's opinion, Dr Russell's sea water cure, spa buildings sold.

8. Recriminations and decline (1750-1780): efforts to resurrect the spa, spurious claims, medical profession's opinion, Dr Russell's sea water cure, spa buildings sold.  9. The First History of Epsom: the 1769 account from Lloyds Post.

9. The First History of Epsom: the 1769 account from Lloyds Post.  10. The Heritage Spa: late eighteenth century and beyond.

10. The Heritage Spa: late eighteenth century and beyond.  11. Other mineralised springs.

11. Other mineralised springs.  12. The Hydrogeology and Geochemistry of Epsom Wells: Symond's and Livingstone's well.

12. The Hydrogeology and Geochemistry of Epsom Wells: Symond's and Livingstone's well.  13. Epsomite Stratigraphy elsewhere: Isle of Wight.

13. Epsomite Stratigraphy elsewhere: Isle of Wight.  14. Reviewing the demise of Epsom Spa, with hindsight.

14. Reviewing the demise of Epsom Spa, with hindsight.  15. Placing the Demise in a Scholarly context.

15. Placing the Demise in a Scholarly context.  16. Epsom Salts, Epilogue.

16. Epsom Salts, Epilogue. Acknowledgements:

Jeremy Harte of Bourne Hall Museum is particularly acknowledged for his scholarly editing and refereeing of the text.

Revd. Dr L W Cowie, J Harte, D Brooks at Bourne Hall Museum, Thornton Ross, Harris Hart, D McArthur of Spa Cottage, William Blythe, Thomas Jackson, Bob Adamson, Graham Cowlin, Dr D Gaimster, M Exwood, Dr A Sacula, C Weaver, Corporation of London staff at Ashtead. Hazel Lintott.

Illustrations for Chapter 16 supplied by Graham Cowlin of Epsom where indicated. These photographs date from 1989/90

Glossary of terms

Alum - double sulphate of Aluminium and another element especially potassium or iron. Before the advent of chemistry c.1800 the term referred to a range of sulphate minerals including Epsom Salts.

Anhydrite - Calcium Sulphate.

Calcite - Stalagmites and stalactites - Calcium Carbonate - resulting from the chemical deposition by water, usually underground. Tufa is a similar deposit above ground. Lapis calcarius is where the crystals are used as gems. Higher temperatures and lower pressures reduce the dissolved carbon dioxide giving the following reaction:

Ca(HCO3)2 = CaCO3 + H2O + CO2

Calcium Bicarbonate - Ca(HCO3)2

Epsom salts - Magnesium Sulphate, MgSO4.7H2O, Epsomite.

Epsom Salts are a domestic saline purgative which according to the British Pharmaceutical Codex (1954),when taken by mouth decreases the normal absorption of water. This causes bulky fluid contents to distend the bowel, active reflex peristalsis is excited and evacuation of the watery contents of the intestine occurs in one to two hours.

Glauber Salts - Calcium and Sodium Sulphate, CaSO4.Na2SO4, Glauberite. BPC. Na2SO4,10H2O.

Gypsum - Calcium Sulphate, CaSO4.2H2O.

Marble - recrystallised limestone resulting from thermal metamorphism.

0.3. Epsom looking towards the former Wells by Hassell 1816.

Introduction

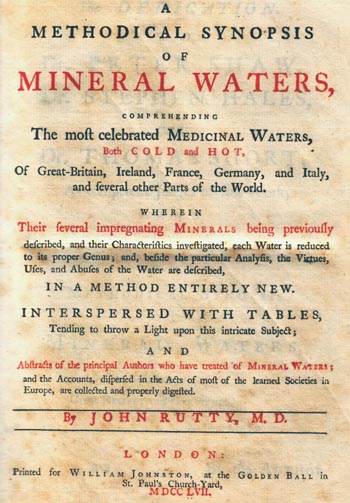

When John Rutty M.D. published his magnum opus on the characteristics of natural waters in 1757 it followed a diligent and exhaustive research into the analysis and nature of mineral springs and wells. His Methodical Synopsis of Mineral Waters was soon recognised as a masterpiece of science and has subsequently become the definitive work on the understanding of spa waters in the mid 18th century. What Rutty did so effectively was to bring together and amplify the understanding of the mineral composition of waters. Contemporary methods of analysis, rudimentary by modern standards, matched the understanding of chemistry of the time. Waters were evaluated for their taste, smell and colour, and their effect on other substances found in nature. Waters were also judged on their effects on the human body, both internally and externally and their action on organic matter, both animal and vegetable. Elements, compounds, chemical equations and atomic weights were still in the future. Rutty particularly built on the works of other scientists of note; Drs Short, Hoffman, Russell, Grew, Brownrig, Charleton and many more legends in their day are all carefully referenced in the margins. Rutty's work was a milestone in two ways. First it recorded for posterity, in a most comprehensive way, the state of the art of mineral water analysis both in England and abroad. In doing so it endorsed, consolidated and legitimised the research of the previous hundred years. Secondly, Rutty's work was a milestone for Epsom. Epsom waters were considered by Rutty at length and from his text we are able to gauge the accepted notions of the day with regard to analysis and composition. Why is this important?

0.4. Dr Rutty's tome on the characteristics of natural waters, 1757.

Rutty's work of 1757, reviews Epsom waters at a time when it will be shown that Epsom as a spa was in the latter stages of terminal decline if not defunct. Using the work as a benchmark, we can deduce how the understanding of the chemistry of Epsom mineral waters had changed in the previous 100 years and how this changing perception had influenced people's ideas on the attributes of Epsom spa waters. For example, Rutty makes a detailed inquiry into the nature of factitious Epsom Salts, which he sees as a cheat when sold as the real thing but nevertheless a useful medicine. The salt makers of Lymington produced the factitious salt at the time. When compared with the true Epsom waters he found different shaped crystals, different solution properties and different effects on fresh blood. In other words, the scientific community accepted that by the mid 18th century that there were two forms of Epsom Salts - real and factitious. Had this knowledge been known, generally accepted and available to the public sixty years previous the heritage of Epsom Spa could well have been entirely different, as will be shown.

Rutty's work of 1757, reviews Epsom waters at a time when it will be shown that Epsom as a spa was in the latter stages of terminal decline if not defunct. Using the work as a benchmark, we can deduce how the understanding of the chemistry of Epsom mineral waters had changed in the previous 100 years and how this changing perception had influenced people's ideas on the attributes of Epsom spa waters. For example, Rutty makes a detailed inquiry into the nature of factitious Epsom Salts, which he sees as a cheat when sold as the real thing but nevertheless a useful medicine. The salt makers of Lymington produced the factitious salt at the time. When compared with the true Epsom waters he found different shaped crystals, different solution properties and different effects on fresh blood. In other words, the scientific community accepted that by the mid 18th century that there were two forms of Epsom Salts - real and factitious. Had this knowledge been known, generally accepted and available to the public sixty years previous the heritage of Epsom Spa could well have been entirely different, as will be shown. With Epsom we have a spa heritage that is unusual in that the resort suffered what was arguably a premature demise. It will be demonstrated in later chapters that resorts behave in accordance with the life cycle model and that periods of demise can be understood as part of a natural process. Epsom's heritage is particularly important in formulating such a hypothesis. This in turn indicates why history is important and worthy of recording and conserving.

Our heritage is what we inherit from the past and it performs a number of roles. Each locality has a heritage that is pertinent to it and no other location. You cannot recreate heritage, in spite of the modern tourism industry striving to do just that. What you end up with is a parody that mirrors something in the past. Heritage therefore makes a place unique and it cannot be duplicated in its real form.

Conservation of our heritage, particularly recent heritage, panders to the human psyche. We enjoy indulging in nostalgia, how things were once, particularly when we were children and shielded from the harsher realities of life. Such sorties into our memories are inevitably distorted and we use the part truths to indulge ourselves in a reality of dreams.

There is however a further consideration of the role of heritage that outweighs uniqueness and nostalgia. It relates to the higher cultural process of humankind. Heritage enables us to interpret the past and understand how the present has evolved from the past. As individuals it gives us a sense of position, role and place in the passage of time and human endeavour. We are able to comprehend our circumstances and our role in changing them and this is a rewarding and constructive faculty.

What happens then when we lose or destroy our heritage, often through default rather than design? What we do is we loose the ability to interpret the past and gain the understanding and insights afforded by heritage. The loss may not be ours, but that of those who follow. They will loose the fulfilment that results from the cultural processes that heritage invokes.

This book is all about bringing together strands of heritage and recording and re-evaluating them to give a clearer comprehension of Epsom and Ewell and their roles as spa resorts. Although the usage of the word 'spa' did not occur until the end of the 16th century in England when drinking waters became popular, the earlier 'baths' are today what we would term as a spa facility; here the term 'spa' is used throughout for convenience. Spa resort heritage is not a complete record that we can read like a mathematical table. What we have are clues and pieces of a jigsaw that do not fit well together. The missing pieces prevent us seeing the complete picture; instead it is necessary to make deductions, based on speculation and evidence of varying quality. Like Rutty we conclude and record the best hypothesis of the day. Also like Rutty, our own research will be later re-evaluated in the context of new knowledge: this is how progress is made.

Epsom is a fascinating historic health resort with an unusual and unique heritage. Its name is famed worldwide to the point where Epsom Salts are so imbedded in our vocabulary of medicine that they have become part of our cultural. Epsom Salts without doubt played a key role in the scientific development of chemistry and the evolution of understanding of elements and compounds and in the discovery of how atoms and molecules provide the basic building blocks of all matter. Such a worthy past requires greater recognition than is currently enjoyed. Perhaps this book will go some way towards redressing the balance.

Illustrations:

Introduction

0.1. Cover - The Old Wells 1662 by Schellinks.

0.2. Proprietory packs of Epsom Salts.

0.3. Epsom looking towards the former Wells by Hassell 1816.

0.4. Dr Rutty's tome on the characteristics of natural waters, 1757.

Chapter 1

1.1. Bourne Hall Lake as it was in 1860 from Swete S J (1860) Hand-Book of Epsom.

1.2. Ewell Spring c.1900.

1.3. Map of Ewell showing the springs.

1.4. Watercolour by L J Bentley, 1977 showing the Ewell Dog Gate with the same view in 2012.

1.5. The Dipping Place, Ewell, 1997.

Chapter 2

2.1. Lake and Grotto, echoes of the past, derelict in the grounds of Ewell Castle. [5 pictures]

2.2. Diana of Ephesus at Villa D’Este (courtesy Due Berry 1998).

2.3. Nonsuch Palace in 1568, from Swete 1860.

2.4. Nonsuch Lodge c.1810. Brayley's History of Surrey.

2.5. The Japanese water park at Ewell in its prime. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

2.6. The Grotto and Bath, Stourhead.

2.7. Popes Grotto on the banks of the Thames.

2.8. Map of Nonsuch, showing the location of the Palace, Banqueting House, Nonsuch Pottery site and possible sites of the Grove of Diana.

Chapter 3

3.1. The well at Spa in 1603 on the front cover of Crismer's 1983 (first edition) book.

3.2. The Willmore Pond and stream tracking northward between Ebsham (Epsom) and Ashtede (Ashtead) in the vicinity of where the Epsom Wells were to be later located. Norden 1594.

3.3. Dorothy Osborne, an early visitor to Epsom to take the waters. Moore Smith C G.1928.

Chapter 4

4:1. Schellinks drawing of Epsom Well, 1662./ Samuel Pepys.

4.2. When the back is turned, early cartoon.

4.3. Charles II with Nell Gwyn. Melville 1923.

4.4. Shadwell's 17th century Epsom Wells, performed in 2001 by the Ralph Richardson Memorial Studios, Wood Green, directed by John Tarlton.

Chapter 5

5.1. Nehemiah Grew.

5.2. The Epsom Old Well in the 1980s showing the Epsom Salts water during construction of the new well head. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

Chapter 6

6.1. Livingstone's New Wells, after Clark (1960).

6.2. The Spread Eagle is an early building dating from the spa era that has survived.

6.3. The Albion Hotel was a coffee house during the spa era adjacent to the New Wells. The present name dates from the 19th century. It is part of a group of surviving buildings at 128-132 High Street.

6.4. Early Epsom showing the clock in the High Street and the New Tavern to the right. 6.5 The New Inn or Tavern 1706.

Chapter 7

7.1. Map of Epsom c.1768 as published by John Rocque, at the end of the spa era showing the Old Wells isolated on the common.

7.2. The New Tavern and Assembly Rooms, later Waterloo House in the High Street was erected in 1692.[9] Facilities included the New Tavern itself, coffeehouse, longroom, cockpit, stables, storehouse and brew house together with ground of about two acres including a bowling green.[10]

7.3. Durdans circa 1825 from Pownall.

7.4. Sally Mapp the bonesetter by Hogarth. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

7.5. Pownall's 1825 picture of Epsom Old Wells showing the pump and beyond, to the right, the building containing the long light (Assembly) room that Celia Fiennes observed.

7.6. The Assembly Rooms at the Old Wells later used as a cottage. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

Chapter 8

8.1. Old View of Epsom Wells, from Keene, 1882/4, Greater London, a Narrative of its History, its People and its Places.

8.2. William Owen's advertisement for mineral waters available in London, 1769.

Chapter 9

9.1. John Ogilby's road map of 1675, Ewell to Dorking showing the Epsom (Old) Well.

Chapter 10

10.1. Epsom High Street in late Victorian times showing the public hall and the town pump, not for Epsom Salts Water but as a supply of fresh water for the townsfolk.

10.2. Epsom Old Well circa 1960. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

10.3. The Magpie Inn now renamed Symond's Well, is thought to be a building dating from the spa era. The "Sign of the Magpie" is mentioned in 1754.[28]

10.4. Epsom Old Well 2010, reduced to something more in keeping with an ornamental gnome garden than a place where scientific history was made.

Chapter 11

11.1/2. Warren Old Well in ruins c.2000./Warren Old Wellhouse early 20th century.

11.3. Jessop's Well with author c.2000.

11.4. Vicki Forbes, Community Woodland Officer at Ashtead Well, 1996.

11.5. Site plan and cross section of possibly two wells in Ashtead Oaks following a field survey in 1997.[25]

11.6. Ashtead War Memorial and defunct Fountain - a twentieth century reminder of an earlier heritage.

11.7. The Old Well at The Warren, circa 1900.

Chapter 12

12.1. Geological table showing the sequence of sedimentary beds.[9]

12.2. Simplified Geology of the Epsom District, showing how the artesian wells of the London basin penetrate the chalk aquifer whereas the saline wells of Epsom only reach the Woolwich and Reading Beds.

12.3. Borehole sequence at East Street Waterworks 1960 by Epsom and Ewell Water Department, supplied by Bourne Hall Museum.

12.4. Historic analyses of Epsom Salts in various wells.[19]

12.5. Epsom salt content of wells and distance from geological surface boundary.

12.6. Relationship between well concentration and distance from the geological boundary. The upper line represents the concentration and the lower line the distance. A letter identifying the origin of the analysis suffixes the New and Old Wells analyses.

Chapter 13

13.1. Alum Bay from a 20th century postcard.

13.2. The Solent syncline with continuity of strata demonstrated.

13.3. Early section of Whitecliffe Bay, the plastic clays are the Reading Beds, the Bognor Clays the London Clays.

13.4. Alum Bay mid 19th century. [12]

Chapter 14

14.1/2/3. Crowds at Epsom Races, 19th century prints from Illustrated London News.

14.4. Epsom Old Well in the early 20th century from Home G. (1901) Epsom.

Chapter 15

15.1. Horse Racing and water reincarnate - local water bottled for the grandstand at Epsom, early 21st century.

15.2. The south eastern section of Andrews 1797 map of mineral waters and bathing places in England and Wales.

15.3.Incremental growth curve for Health Resorts.

15.4a/b/c. The Resorts Life Cycle Model - tables of key indicators and their respective characteristics at various developmental stages.

Chapter 16

16.1 The Old Manor House.

16.2 The White House.

16.3 Yew Tree Cottage.

16.4 109-113 High Street.

16.5 Marquis of Granby.

16.6 26-28 South Street.

16.7/8 55 South Street.

16.9 Woodcote Green House.

16.10 8-10 Chalk Lane.

16.11 Chalk Lane Hotel.

16.12 Maidstone House.

16.13 16 Waterloo Road.

16.14 28 and 30 Waterloo Road.

16.15 The Old Pines, The Parade.

16.16 The Stone House.

16.17 The Old Vicarage.

16.18 Parkhurst House.

Email: info@thespas.co.uk (click here to send an email)

Website: Click Here

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

1) TOPOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

England

3) INFORMATION CATEGORY:

Springs and Wells General InterestHistory & Heritage