|

|

CHAPTER TEN

ORGANISATIONAL RESTRUCTURING

AND MARKETING STANCE FOR TOURISM.

AND MARKETING STANCE FOR TOURISM.

The Malvern case study raises the question of how an effective policy and management plan can be prepared for tourism, particularly when it is such a broad ranging concept that it percolates into so many aspects of human behaviour.[1] The diverse nature of tourism has already been commented on in Chapter 4. In addition, tourism involves such a wide range of agencies and disciplines that have a direct interest in visitor recreation and its impacts, that no existing body has a sufficiently wide remit to cope with all key aspects. In spite of this tourism needs to be effectively managed to accommodate the environmental, social and economic ambitions of the community.

This chapter seeks to develop a viable approach to tourism policy and management and in subsequent chapters the environmental, social and economic implications are considered. In the investigation of tourism structures and planning, the evidence from the two case studies, Dartmoor National Park and The Malvern Hills AONB, is enlightening. This chapter develops an approach to organisational restructuring which in turn leads to a review of the implications of key agencies policy unification. The chapter concludes with a debate in which tourism marketing is explored in the context of the earlier propositions.

The two case studies have each been selected because they illustrate different facets in the development of tourism and the pursuit of environmental, social and economic aims. Each of the case studies manifests different levels of success with the criteria under scrutiny. This enables comparisons to be made with the Sussex Downs. By distilling the strengths, weaknesses and methodology that has led to particular outcomes from each of the case studies, it is possible to suggest how the environmental, social and economic aims may or may not be progressed to advantage within a debate on tourism policy and management.

To illustrate this approach, the Sussex Downs have been part of an exceptionally dynamic economic region during the twentieth century. This in turn has led to major development impacting on the Downland. Brandon and Short point out that the region at large has a stereotypical image of beautiful countryside but has now taken on a mantle of representing England's despoliation.[2]

The Malvern Hills, by contrast, have not undergone the imposition of aggressive development and commercially orientated tourism during the comparable period but have been particularly successful in the protection of the environment. Dartmoor, with 40 years of experience as a National Park, has secured regional development from tourism without the degradation of the environment that other National Parks, such as the Lake District, have experienced.[3] These issues are summarised in Table 10:1.

Table 10:1 Environmental Tourism & other

Conservation Development

Conservation Development

Sussex Downs Low High

Malvern Hills High Low

Dartmoor High High

Tourism Development and Conservation.

Looking in greater depth at the case studies, a number of points relevant to the pursuit of tourism are apparent.

Both case studies pursue tourism development capability based on outdoor recreation. The marriage between environmental conservation and visitor management is of key importance, therefore, if this capability is to be harnessed to advantage.

In the case study of Dartmoor a number of observations are pertinent to the successful marriage of the environmental and economic development aims.

i) The planning function within the NPA is already pursuing local plans for integration into the County Structure Plan. This position is considered inadequate. The ability to be self determining with regard to planning is covered in the Review Panel proposals to establish the NPAs generally as Independent Authorities.

ii) Under recreational strategy set out in the Second Review Plan, new enterprises are located outside the National Park core area. This supports a philosophy of conserving the core area as managed wilderness with the higher impact commercial infrastructure of tourism sited in a peripheral zone.

iii) There is a regional initiative which encompasses an area considerably greater than the National Park. The Dartmoor Area Tourism Initiative, supported by the Tourism Development Action Programme (TDAP), enables management plans and policy issues to be unified by a forum representative of the greater region.

iv) Considerable resources are invested in visitor research to enhance understanding of key issues.

v) The economic development and environmental conservation aims in the core area may result in an imbalance of social factors that work to the disadvantage of the local populace, as the emphasis moves towards conservation and away from commerce. Dartmoor, like its counterparts elsewhere, is a landscape in which people have to thrive and prosper.

vi) Bureaucracy may jeopardise action as organisational complexity increases.

In the case study of the Malvern Hills a different set of considerations emerge.

i) The region has not been able to successfully marshall its resources to produce a significant tourism based economic initiative since the mid 19th century.

ii) The locality has enjoyed particularly effective environmental conservation. The built environment has not been unduly assaulted by the economic booms and building programmes of the twentieth century. The natural environment has become fossilised by the draconian restrictions of the Malvern Hills Conservators Acts and the restrictive management policies of the Conservators.

iii) A general intransigence towards economic growth is identified within the populace. This results from a powerful lobby within the decision makers which has little vested interest in economic prosperity; this lobby represents retired and mature individuals living off historically generated wealth.

iv) There is a generally accepted notion that tourism development is synonymous with negative impacts.

An amalgamation of the key elements from the case studies provides a menu which can now be considered in detail as being pertinent to tourism policy and management formulation. This menu is now considered in the context of the debate on Downland tourism policy and management. This is followed by a discussion on how the issues may be orchestrated and the benefits that can be anticipated.

There are two main elements that can be distilled from the case studies.

First, the need for a regional tourism policy and management package that extends beyond the bounds of the core region. In the case of the Sussex Downs this would incorporate the aggressively marketed tourist resorts of the south coast as well as the Wealden area to the north, where selected and appropriate infrastructure could be established. Such a move entails the creation of an organisational structure to unify the objectives, strategies and tactical management programmes of the wide variety of agencies with an interest in tourism - a Sussex Area Tourism Initiative (SATI) leading to a Tourism Development Action Programme.

Second, the establishment of enhanced statutory powers to enforce planning objectives in the core area. This requirement is apparent in both of the case studies. It enables not only the geography of tourism to be manipulated but also ensures the conservation of the core area landscape. On Dartmoor, the need to increase statutory planning powers is identified in the Review Panel proposals. On the Malvern Hills, the statutory powers of the Conservators have proved particularly effective in conserving the natural environment. This issue is pertinent to the future status of the Sussex Downs which has suffered environmental degradation. It is therefore considered in further detail in Chapter 14 which debates the merits of future National Park or AONB designation.

In addition, emerging from the case studies, there are several secondary issues which can now start to be considered.

Visitor research has already been recognised as important for the Sussex Downs and a programme implemented as part of this overall study.

Intervention in the economic development of the landscape to facilitate conservation runs the risk that the economic and social well being of the communities may suffer, this issue is considered under the social and economic impacts in Chapters 12 and 13.

Bureaucracy may jeopardise action and this is seen as a problem of not segregating policy making from management action. This issue is discussed in the context of a Sussex Tourism Development Action Programme.

Reluctance to embark on economic development through tourism, due to notions that the outcome will result in adverse impact is a major brake on development in Malvern. This is considered under restraints on development in Chapter 13.

How might an area tourism initiative be orchestrated to overcome many of these problems?

Sussex Area Tourism Initiative (SATI) and Tourism Development Action Programme (TDAP).

In the development of a regional policy and management package, the three factors that a Sussex regional tourism initiative should seek to accommodate are the diverse nature of tourism, the geography of tourism and third, the nature of the Downland tourist experience and product.

The diverse nature of tourism is discussed at length in Chapter 4. Because of the variety of facilities that tourism utilises, ranging from accommodation to entertainment and transport and the varied nature of tourists themselves, including general outdoor recreationalists in the case of the Downland, an elaborate social and commercial infrastructure is necessary to support tourism. In order to steer and manage tourism development a wide spectrum of disciplines needs to effectively participate. In the organisation of society, such interests are focussed in a range of organisational structures that deploy their specific views and expertise to an end. In the case of tourism no single body is positioned to speak for all, it therefore becomes essential to integrate key bodies to bring about a unification of approach, in the form of a SATI.

The geography of tourism plays an important part in determining the representation on a SATI. It has previously been noted that the study area divides into three distinct regions.[4] These are illustrated in Figure 2:4. To the north there is the Weald which has the potential for accommodating some of the commercial infrastructure of tourism, in particular rural accommodation and tourist attractions that are not sympathetic to the Downland tourism experience based on quiet outdoor recreation.

The core zone comprises the Downland itself. This is the landscape where the visitor enjoys the product determined in Chapter 7, essentially an outdoor experience where walking and exploring are important, a rolling green landscape that encapsulates the rural idyll of the "south country". In this core zone environmental conservation is mandatory if the visitor experience is to be secured. This in turn establishes the need for conservation interests to be integrated into a SATI organisational restructuring.

To the south there is the coastal strip. The south coast resorts have been shown to provide massive bedspace potential as well as already possessing the entertainment and service facilities of commercial tourism.[5]

The adoption of a zoned approach has been successfully implemented as part of a deliberate policy in the Dartmoor case study. In the case of the Malvern AONB, the identity and conservation of the core area has come about through historical circumstances. In a similar manner to the case studies, the Sussex Downs is able to accommodate the demands for the unadulterated experience in the inner core area with the potential for infrastructure utilisation and development in the surrounding peripheral zones. Where the Downland gains an advantage over Dartmoor however is that, because of the extended shape of the Downland, there is no area that is far from the vibrant economies and facilities of the perimeter zones. The geography is such that being some thirty miles in length and between five and fifteen miles wide, the Sussex Downs is easily traversed with a pattern of north south routes. In addition, along its length, the eventual Honiton to Folkstone trunk road will provide latitudinal movement with ease. The only regret is that such routes have carved gashes across the irreplaceable basic resource, the Downland. In spite of this, every part of the Downland is quickly accessible from the surrounding districts. This includes the major south coast resorts to the south and the Wealden towns and villages to the north. In this way the ease of passage of goods and people avoids both spiritual and economic isolation.

Zoning in this manner is not a new concept. Each of the six National Parks in France contain a core area surrounded by an access zone, the latter carrying the visitor infrastructure.[6] County structure plans have similarly delineated zones of permitted development since their inception. Where the Area Tourism Initiative differs is in both the proactive action programme that emerges and the coordination of representation to bring about the coordinated effort.

Any regional tourism initiative needs to accommodate representation from all of the geographical areas and key disciplines. These in turn contribute to the total initiative through the unification of policies and resources. In addition those with a primary direct interest in the Downland, such as farmers and land owners, also need to actively participate in the debate.

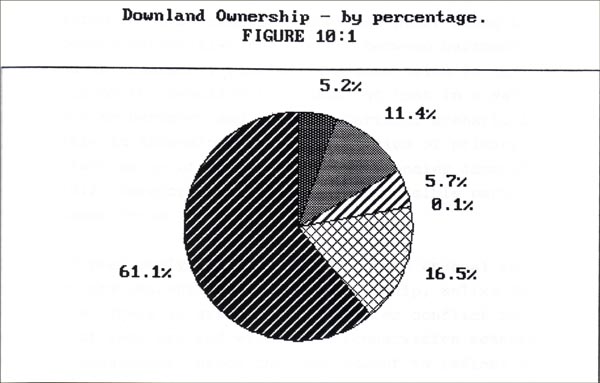

But who at present owns and manages the Sussex Downs? In the three opening chapters a diverse range of agencies are identified as having responsibility for part or all of the Sussex Downland. Table 3:8 summarises conservation measures and agencies and attempts to rank them according to their ability to implement their remit. These can be divided into two groups, firstly, those with the primary function for managing the land, the land owners and long term leasees, which fall into a complex network of part public and part private holdings. The second group are agencies with a secondary role in influencing land use in that they are not the land owners. These include MAFF through farm incentives, English Nature through SSSI management etc. The first group can be identified and quantified as set out in Table 10:2.

Table 10:2

Who owns the Sussex Downland?

Table 10:2

Who owns the Sussex Downland?

hectares percent

National Trust 3966.0 5.2

ESCC + WSCC 814.0 1.1

Brighton 5666.0 7.4

Eastbourne 1619.0 2.1

Adur 400.0 0.5

Lewes 163.0 0.2

Forest Enterprise 4321.0 5.7

Sussex Wildlife Trust 104.0 estimate 0.1

Estates as Table 3:7 12611.0 16.5

Other land 46626.0 61.1

National Trust 3966.0 5.2

ESCC + WSCC 814.0 1.1

Brighton 5666.0 7.4

Eastbourne 1619.0 2.1

Adur 400.0 0.5

Lewes 163.0 0.2

Forest Enterprise 4321.0 5.7

Sussex Wildlife Trust 104.0 estimate 0.1

Estates as Table 3:7 12611.0 16.5

Other land 46626.0 61.1

Total core Study Area 76300.0 100.0

source: Chapters 2 & 3

The primary management of the Downland can be seen to be the responsibility of three principal sub-groups, 1) miscellaneous unidentified private landowners representing the largest proportion, 2) substantial estates and 3) assorted public ownership. The percentage figures given compare with Dartmoor National Park as detailed in Table 10:3.

The Table 10:2 percentage data, with County and Local Authority ownership grouped together, can be represented on a pie chart as in Figure 10:1.

Clockwise Key - National Trust: Public Authorities: Forest Enterprise:

Sussex Wildlife Trust: Estates: Other.

Sussex Wildlife Trust: Estates: Other.

Table 10:3 Land control comparison.

(Percentage) DARTMOOR SUSSEX DOWNS

National Trust 3.7 5.2

Forest Enterprise 1.9 }5.6 5.7

Water Authorities 3.8 }

NPA 1.4 0

Ministry of Defence use 14.0* Estates 16.5

NCC, English Nature 1.4 Wildlife T. 0.1

Other Duchy lands est. 17.0 Councils 11.4

Private/miscellaneous 56.8 61.1

Forest Enterprise 1.9 }5.6 5.7

Water Authorities 3.8 }

NPA 1.4 0

Ministry of Defence use 14.0* Estates 16.5

NCC, English Nature 1.4 Wildlife T. 0.1

Other Duchy lands est. 17.0 Councils 11.4

Private/miscellaneous 56.8 61.1

source: see footnote [7]

* includes some Duchy of Cornwall Lands which in total amount to 29.6% of NP.

From the comparative data in Table 10:3 it is apparent that, in many respects the figures for Dartmoor are similar to the Sussex Downs. The exception is for the Ministry of Defence land. No such ownership occurs on the Downland. On Dartmoor, MOD holdings include Duchy lands. However if the MOD is substituted for substantial estates and other Duchy Land for Local/County Authorities the pattern between Dartmoor and the Downland is remarkably similar. The conclusion is that land ownership on the Downland is typical of that in a National Park such as Dartmoor and that the Dartmoor scenario is invaluable in assessing the representation of primary land controllers on an effective SATI. The agencies identified in Table 10:2 therefore provide a list of possible participants to a common forum.

As noted previously, UK National Parks are unusual in that they are predominantly in private ownership, unlike Parks elsewhere. There is greater potential for conflict between commercial land use and wilderness conservation measures and visitor management. Hence the requirement to reflect such ownership in any decision making body concerned with the environment and tourism. The Dartmoor case study demonstrates that underlying conflicts can be resolved.

In addition, a summary of the agencies who have a secondary role in landscape management and planning on the Downland extends the list of participants in a SATI.

County and District Councils (in turn representing a whole host of operating units within local and county government [8] also see Chapter 13).

English Nature.(SSSIs 5,419.8ha, 7.1 percent of total*)

MAFF.(ESA estimated at 66 percent of total*)

Countryside Commission.

Sussex Downs Conservation Board.

Sussex Wildlife Trust.

County Archaeologists.

National Farmers Union.

Commoners Council or similar.

Country Landowners Association.

Society of Sussex Downsmen and other voluntary bodies.

Council for the Protection of Rural England.

(* core study area, 76,300 ha.)

A further consideration for representation on a SATI are those agencies which have a direct tourism or economic development role in the region.

SEE Tourist Board.

County and Local Authority Tourism Depts.

Rural Development Commission.

Rural Community Council.

Area Museums Council.

Sports Council.

Ministry of Transport.

Dept of Employment.

Commercial agencies responsible for organising tourism.

County and Local Authority Tourism Depts.

Rural Development Commission.

Rural Community Council.

Area Museums Council.

Sports Council.

Ministry of Transport.

Dept of Employment.

Commercial agencies responsible for organising tourism.

It is worth noting at this point that there are thirteen District Councils and three County Councils responsible for different parts of the South Downs in its entirety.[9] Whilst direct representation on a SATI would be cumbersome, representation through tourism officers where appropriate or the old AONB Forum could be considered. This problem is unlikely to substantially change with any forthcoming local government reorganisation.

Rationalising the above listings suggests that there are about 24 key agencies plus Councils that should reasonably be represented on a SATI forum. As well as the general concern about the creation of a new level of bureaucracy which may well defeat the objectives of the exercise, the creation of such a body would also be criticised on a number of other counts. Experience elsewhere gives insights into the concerns.

The recent failed proposal to designate the New Forest as an Area of National Significance with similar status to a National Park has raised a number of issues for debate.[10] The intention was to give an earlier coordination committee, comprising a forum of managing agencies, legal status and power. The objectors have raised two particular public concerns relating to visitor management and tourism. Can tourism be better managed by existing agencies and how can visitor and tourism interests be expressed through representation on the managing body?

Both of these concerns reflect the current thinking on the membership and structure of managing authorities for National Parks. Tourism as a subject is not directly represented on National Park Authorities or the Malvern Hills Conservators. The Sussex Downs Conservation Board does enjoy the membership of a tourism representative. Elsewhere reliance is placed on County Council and indirect representation to voice tourism matters. This omission has been effectively recognised for Dartmoor National Park in the evolution of the DATI, which is arguably far more effective in managing tourism issues because it covers a wider region beyond the bounds of the National Park and coordinates the activities of active tourism agencies as well as the wishes of elected representatives.

This highlights the need for a SATI to be a policy as well as a management determining body. The SATI in effect brings together these two essential components of a tourism initiative which would otherwise be scattered throughout various organisations policy documents and management plans.

A further concern in the New Forest is that any new legally empowered coordination committee would be in a position to over-ride local interests, if its powers are to be of sufficient strength to have any impact. The extent of power given to such a body is a separate debate in itself.[11] It was particularly felt that any outsiders would not understand local issues and the traditional way of life. This concern stems from the ancient establishment of the Forest Verderers as a legal body able to veto planning decisions. The planning authority requires an Act of Parliament to over-rule the Verderers and as such the Verderers are a formidable body able to enforce local planning wishes. The Lyndhurst by-pass was stopped at Parliamentary level. There are similarities here with the Malvern Hills Conservators although the latter have statutory powers based on land ownership and are therefore in an even stronger position.[12]

In the case of the Sussex Downs no such autonomous body has been available to determine planning issues in the past and this has led to the dramatic environmental deterioration and piecemeal encroachment of some parts of the Downland. This issue becomes part of the debate on the statutory powers of the Sussex Downs Conservation Board and is considered further in Chapter 14.

If a SATI forum is established for Sussex, this then raises the question of inherent conflict within stated policies and the unification of such policies. In the case of Dartmoor National Park, the policies for recreation and enjoyment are published in the Second Review Plan and then replicated in the Local Plan. The Local Plan only receives ratification if it accords with the County Structure Plan and a mechanism is already in place for achieving this in Dartmoor and elsewhere. Apart from the Statement of Intent, Malvern has no such local initiative for the AONB and therefore depends on policies determined at County and at District Level, but without the considered SATI forum to steer such policies. This is without doubt a weakness from which Malvern suffers.

Research into the published planning policies and objectives of the key agencies operational on Sussex identifies a similar lack of cohesion.

The Sussex Downs Conservation Board has now widely publicised its objectives. Its stated primary objective relates to the conservation and enhancement of the Downland AONB, in line with National AONB objectives. Subject to the primary objective, the Board then seeks to promote quiet informal enjoyment of the Downs and to promote economic and social development.[13] Tourism development can be orchestrated to be in accord with these objectives but the remit of the SDCB is limited to the AONB. This has been shown to be a limiting factor for tourism development which must be considered over a larger, more diverse region. For the SDCB to influence tourism development over a wider region, a forum is required and a SATI meets this requirement.

The WSCC Structure Plan necessarily takes a wider view on economic and landscape planning issues.[14] There is recognition that the rural economy needs to be maintained in a healthy state and that in the AONB, conservation takes a higher priority (1.34 & 2.6). It is in the detail that the concerns arise regarding policies for the Downland. The Downs are not identified as an area of distinctiveness other than within the AONB (C2). This absence of special treatment then suggests that developments such as golf courses, can be permitted on the Downs subject to certain provisos (C13). No account is taken as to whether the diversification of leisure pursuits that golf courses, or similar, provide is conducive to an overall tourism and visitor management policy pertinent to the Downland as a distinct place. This underlines the need to plan for the Downland as a special place but within the context of the greater region. No single County, District or Parish is able to fulfil this role. A SATI with appropriate planning influence would enable this to happen. Further endorsement of this view comes from the recreation and tourism policies. For example, in allowing development within existing built up area boundaries and sites (R6), does this enable tourist enclaves to be created over time on the Downs at Goodwood and other localities, where infrastructure already exists? If so, is such a development conducive to the aims and ideals of other agencies and to the long term interests of visitor policy and management? Such issues require resolving through a SATI.

Similar comment can be directed at the East Sussex Structure Plan although East Sussex is able to identify the Downland as a distinct area within its plan (S18, WA/L2 etc.). This enables special treatment to be applied. Whilst the structure plan therefore endeavours to accommodate the special nature of the Downland in the form of statements such as "subject to restrictions on the Downlands" (WA/L2 b) and "compatible with the character of Downland" (S18), what this special character is appears to be left to the interpretation of the decision makers.[15] One role of a SATI therefore, in conjunction with all agencies with an interest on a macro level, would be to determine a description of the Downland ideal landscape. This "vision of the Downs" would provide a common framework for the application of supporting policies and management.

In the Economic Strategy for East Sussex, (1991) [16], ESCC recognise that the economic problems of East Sussex are not common to all parts. ".... economic strategy then needs to be a liberal framework within which a diversity of local solutions can be applied according to need." (p7) The difficulty with any economic strategy at County level is that it inevitably becomes generalised. As a result open ended statements have to suffice rather than clearly defined strategic objectives. Tourism falls precisely into this trap. "Tourism and agriculture must change, move with the times - and the change needs to be managed."(p14) Lacking further clarification such statements leave the reader in mid-air. Having stated the obvious where is the particular? The Downland does not feature, highlighting the limitations of current approaches to Downland recreation planning and general tourism management.

The Rural Strategy for West Sussex falls into precisely the same trap. The plan clearly recognises the varied interests and pressures on the rural communities at large, but does not make the Downland a special case. For example, under "recreation" (2.6.1), general statements are made about access to the countryside with attendant facilities near towns, the providing of comprehensive information and guidance and the accommodation of active sports. Such measures could be seen as improving the visitor experience. Such a "product" improvement will increase demand for that product and in the case of visitor recreation, impacts will be increased. A process that may well be inappropriate for the Downland. Recognition is also given to the increase in and changes going on in recreation requirements, particularly new and noisy activities as technology and increased wealth give individuals new horizons for their style of countryside recreation (1.5.12). This leads to proposals on zoning (1.7.7), but not in the context of the Downland as a special place.[17] What is apparent is that, as a general rural development policy, for application in the peripheral study area, the rural strategy policy documents are well suited. What they lack is the recognition that the Downland is a special place requiring special treatment. If the Downland is to be envisaged in such a manner, the joint offices of the SDCB and a SATI need to be used to prepare a "vision of the Downs" policy and management strategy, for incorporation into planning issues that are necessarily dealt with under present legislation by County and in turn District Councils.

Unfortunately the East Sussex forward view of 21st century planning perpetuates the status quo rather than taking a dynamic approach to the Downland.[18]

Underpinning the County Structure and Economic Planning Policies is the Sussex Downs AONB Statement of Intent, published by the joint County Councils.[19] This document dated June 1986 is identical to the Countryside Commission publication of August 1986 outlining Priorities for Action.[20] Neither document addresses the structuring and management of tourism other than in the context of other issues and a general leaning towards recreational facility provision. From the case studies it is apparent that such scant treatment of the complex issues of tourism policy and management is inadequate. The implementation of a SATI forum would enable the precise issues to be brought into focus for the region at large and for the Downland in particular.

Until a detailed investigation is carried out, it is not generally appreciated how little the Downland features in tourism and economic planning of the region at present. This reflects current attitudes about the Downland. Brighton Borough Council, through their Economic Development Unit, have prepared a detailed prospectus to encourage economic growth supported by extensive public works and pump priming, aimed particularly at tourism.[21] In the extensive package of publications there is no mention of the Downland as either an environmental or economic asset. A key role for a SATI would be to orchestrate a new realisation that the Downland is a valuable facility for the Town, comparable with the seafront. The Downland is a potential provider of low cost recreational amenity to the region from which the infrastructure of Brighton can secure substantial economic benefits, both directly and in extending the general appeal of the resort.

The difficulties faced in reconciling Local Authority Tourism objectives are underlined in the findings of the Countryside Commission for the 1990 National Parks Marketing and Conservation Survey.[22] When surveyed, Local Authorities took an insular view of their tourism objectives, citing job creation and the increase in visitor spending as key. "Tourism Departments of Local Authorities are responsible first to their members and to policy objectives for tourism, spending and job creation before accounting to other organisations such as National Park Authorities" (p12). Where environmental considerations are high priority, operating in a vacuum in this manner only exacerbates friction and wastes resources. A SATI provides the means for planning in depth to the long term advantage of all participants.

The difficulty in developing common consultative mechanisms for issues such as tourism is well known.[23] The CPRE underlined the need for a cohesive recreation strategy for the Downs in 1990.[24] At the root of the problem lies the differing objectives of the various participants or agencies. It is insufficient to formulate a common management plan for implementation on a joint basis. The "coming together" necessarily has to be a higher level. Strategic thinking has to be unified with common overall policies debated and adopted. This again underlines the importance of a SATI being both a policy and management body. In the case of the Downland this includes all of the partners identified earlier in this chapter.

A concern expressed earlier was that the involvement of a wide range of agencies in a SATI forum would result in a bureaucracy unable to function effectively. This problem was recognised by Dartmoor ATI, yet in spite of this danger it has been considered appropriate to extend the membership of the DATI in its second term. The wider involvement results in greater effectiveness. Three criteria for the Area Tourism Initiative emerge as critical to the successful implementation of such a proposal:

i) The wish on the part of the participants to achieve results rather than treating membership as a monitoring operation to secure pecuniary advantage when the opportunity arises.

ii) The determination of long term overall objectives at an early stage in the proceedings, based on a "vision of the Downs".

iii) The separation of policy and strategic planning, which should be the remit of the forum, from management programmes, which should be the remit of the TDAP officers and the officers of the member organisations. Dartmoor have particularly recognised this point and officers liaise to underpin the decisions of the steering committee of the DATI.

Member organisations thus become in part accountable to the Area Tourism Initiative forum for the implementation of tactical measures derived from the strategic planning. This has the advantage in the case of organisations such as Tourist Boards in that, not only are their activities in close unison with the overall objectives, but in addition the Tourist Board assumes responsibilities for particular achievement targets and can be monitored accordingly.

Another requirement of a Area Tourism Initiative is to be dynamic in its operation. Attitudes to the conservation of the landscape change as circumstances change. The development of a SATI therefore needs to be sufficiently robust to be able to respond to changing pressures on the landscape in the core area. Blunden and Curry record that in the 1930s afforestation, urban sprawl and ribbon development were primary concerns. By the 1960s this had changed to electric pylons, caravan sites and the motor car. Agriculture would not have been a major concern of the time. By the 1980s agricultural intensification appeared high on the list of anxieties.[25] Today the emphasis is moving towards road building, tourism impact and habitat conservation. Tomorrow's concerns are difficult to anticipate accurately. Low price recreational use of the countryside is destined to increase and the control of the infrastructure of recreation may be the greatest issue. The misguided provision of visitor facilities can unwittingly lead to a plethora of car parks, litter bins, toilets, visitor centres, concrete paths, sign boards and whole host of man made intrusions onto the landscape. The SATI not only needs to be alive to such changing issues but also able to respond to them appropriately.

Another requirement of a Area Tourism Initiative is to be dynamic in its operation. Attitudes to the conservation of the landscape change as circumstances change. The development of a SATI therefore needs to be sufficiently robust to be able to respond to changing pressures on the landscape in the core area. Blunden and Curry record that in the 1930s afforestation, urban sprawl and ribbon development were primary concerns. By the 1960s this had changed to electric pylons, caravan sites and the motor car. Agriculture would not have been a major concern of the time. By the 1980s agricultural intensification appeared high on the list of anxieties.[25] Today the emphasis is moving towards road building, tourism impact and habitat conservation. Tomorrow's concerns are difficult to anticipate accurately. Low price recreational use of the countryside is destined to increase and the control of the infrastructure of recreation may be the greatest issue. The misguided provision of visitor facilities can unwittingly lead to a plethora of car parks, litter bins, toilets, visitor centres, concrete paths, sign boards and whole host of man made intrusions onto the landscape. The SATI not only needs to be alive to such changing issues but also able to respond to them appropriately.

The idea of an integrated rural development programme is not new. The breaking down of inefficient sectorial barriers is an approach gaining favour throughout Western Europe.[26] The SATI approach unifies the efforts of fundamental interests within society, the conservationists, the need for economic development and the needs of the populace both for recreation and as land owners or residents. The involvement of the community through representation, the bottom up approach, arguably provides a more radical and in the long term more efficient and equitable approach to tourism policy formulation and management for the Downland.

There are indications that the benefits of an Area Tourism Initiative are being recognised in the South-East. In an effort to halt the decline in tourism in West Sussex a County Initiative was launched on 23 Sept 1993 by the County Council. The first stage was the establishment of a working party. The stated intention being to develop a closer working relationship between the private and public sectors of the industry and to create marketing initiatives that are economically beneficial but environmentally sensitive. It is envisaged that the establishment of a County wide forum would enable funding to be consolidated to a common endeavour as well as acting as a dynamo for tourism development generally.[27] One particular aspect of the WSCC initiative is the possible provision of training.[28] This potentially extends the remit of an ATI beyond a policy and management agency and may dilute the effectiveness. Such training as is appropriate may better be provided through a sub contractor or provider such as a University.

Criticism of the Area Tourism Initiative working party however has been forthcoming. Meetings and discussion are seen as an alternative to hard decision making. The alternative view proposes that money should be set aside for promoting tourism along similar lines to adjacent successful Counties. Individuals should then be briefed to deploy the monies effectively.[29] Such criticism fails to convince on two counts. First, the availability of money is not in accordance with current financial constraints being imposed on such public spending - hence the need for coordinating finance from a range of agencies. Secondly, a stand-alone initiative, not coordinated with all the principal vested interest agencies and disciplines fails in effectiveness as can be seen from the Malvern Hills case study.

The development of the Area Tourism Initiative through the working party in West Sussex has significant prospects for the County. In August 1994, it was announced that the Initiative was being developed as a private marketing company, the principal function of which is to market the area.[30] Whilst this may provide a vehicle for the unification of promotional spend, it fails to provide a policy and strategy framework across a wide range of agencies and issues. The outcome of the deliberations are awaited, although at this stage it will unlikely meet the requirements and composition of the SATI proposed in this document.

If the public environmental, economic and social needs relating to tourism are to be voiced and managed through a SATI, what philosophies and approaches can be adopted in the marketing of tourism in the region concerned? This is discussed in relationship to the visitor experience and the provision of the tourist product to consume. A differentiation is made deliberately between the experience, that is the enjoyment of the product and the product itself, the landscape and infrastructure that are necessary components of a tourism industry.

Marketing has come a long way in the last thirty years. The coordination and development of resources to meet an identified need, to secure an advantage, means that marketing as a discipline is an integral part of tourism management. Marketing to many is epitomised by the proactive, aggressive approach with a sharp eye on the "bottom line" typified by the mass market techniques of advertising agencies and multinational corporations. This raises the question: can a similar approach be made to the commercial marketing of, say, a mass market food product as to the marketing of a tourist locality such as the Sussex Downs?

In the case of the food product, the marketing is a sophisticated process of resource focussing and product development as the marketeer prepares and launches a product into the market place. In this process the needs of the consumer dominate. The product is styled to meet a distinct market opportunity and the target consumers are carefully identified, as are the necessary product attributes, both real and perceived. The nature of the product itself and the packaging are developed to give the optimum production effectiveness together with handling and presentation that ensures that the finished good is both cost efficient as well as of high consumer appeal. Detailed research ensures that the product will fulfil expectation as well as stand up to competition. Carefully targeted advertising then projects the honed message of the qualities and imagery of the product to the trade and consumer. In this way the commercial opportunity is optimised and the volume/price relationship enables the marketeer to make a substantial return on the investment involved.

Is it reasonable to adopt a similar approach to tourism planning? For the commercial sector, faced with a competitive operating environment the answer is, arguably, yes. To compete in a capitalist, free market economy successfully necessitates all the sophisticated techniques of modern marketing being brought into play, but there are a number of considerations which make it totally inappropriate for the Sussex Downland experience and "product".

The pursuit of financial gain is not the purpose of the AONB. The "bottom line" is not profit. The Sussex Downs represents a major national public asset which is seen as something worthy of retention as a distinct entity for future generations to enjoy in its traditional form. Tourist needs are not the dominant factor. The development and exploitation of the Downland in a commercial manner is in diametric opposition to the stated policies of conservation and public recreation for the good of all. The landscape would change out of recognition as the commercial interests of the venture capitalist replace the ideals of the conservation and public recreation movements.

If proactive "product development" and aggressive marketing is inappropriate for the Downland, is there an alternative stance that can be adopted as the basis for pursuing the conservation as well as the tourist needs as identified earlier in this chapter?

One alternative is to demarket the Downland, to avoid any form of product change which is tourist orientated and to set positive barriers to the use of the Downland by tourist and commercial interests. Access can be denied and facilities removed. For example, access agreements under Countryside Commission/MAFF schemes need not be renewed, car parks can be removed preventing casual pulling off the road and facilities such as The Cuckmere Valley Country Park can be closed.

Whilst this approach may meet the wishes of many alternative users of the Downland, especially commercial agriculture, it again is diametrically opposed to the philosophy of public access and recreation. In addition such an approach ignores the valuable contribution that tourism can make to the local economy and environment. It also removes marketing as a crucial tool in managing and directing the development of tourism.

What therefore is an appropriate marketing philosophy to adopt in the formulation of tourism policy and management for the Downland? This is a fundamental question, the answer to which is of prime importance to the future of the Downland.

In search of the answer it is again useful to look at experience elsewhere. 40 years of experience and expertise developed by the Dartmoor National Park is invaluable in exploring appropriate marketing further.