|

|

- A CASE STUDY.

"Never in the history of Malvern was there a time when she more needed a good word and helping hand than now. Numbers of houses are empty, Malvern Wells is half depopulated, and North Malvern is well placarded with bills `To Let`......Malvern has nobody to look after its interests and lay its beauties before the public. Mr Editor, I am well nigh ashamed I am a resident here, and often despair of the future of this lovely town...."[1]

This Victorian editorial suggests that the pursuit of economic prosperity through tourism is not new to Malvern. Today the local people recognise that tourism is a possible, yet elusive, means of reviving economic fortunes. Malvern has enjoyed unprecedented conservation of the built and natural environment. Architecture remains predominantly Victorian and the 19th century infrastructure such as gas lamps or roadside springs and watering points remains unnoticed in its original state to be rediscovered by the local historians.[2] Forming a back cloth to the town, the Malvern Hills have successfully resisted all attempts at commercial exploitation over the last 100 years. The Sussex Downs, by contrast, have succumbed to major economic exploitation, including tourism, at the substantial expense of the natural environment. This case study investigates the background to Malvern's economic stagnation and the present day relationship between what are seen by many as two opposing forces, tourism development and conservation of the environment. The efforts being made to progress both illustrate the confusion that is in turn negating effort. Later in this thesis, this case study, in tandem with other data, will be used in formulating the debate on the rationale and methodology for tourism development, encompassing the needs of environmental conservation, on the Sussex Downland.

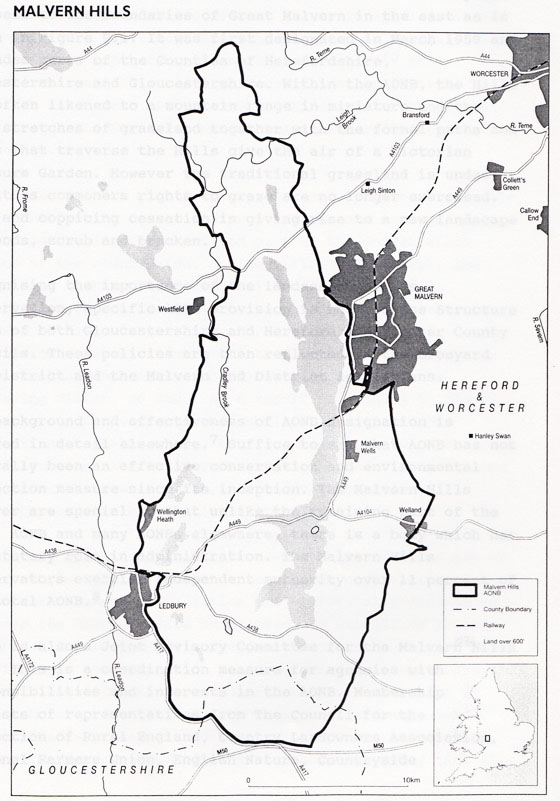

Background The Malvern Hills comprise a north-south Pre-Cambrian ridge, about twelve kilometres in length, up to 425 metres high, separating the flat Severn plain to the east in Worcestershire from the rolling Triassic and Silurian geology and landscape to the west in Herefordshire.[3] The particular topography has attracted the activities of humankind for thousands of years. Ancient Hill Forts, mines and quarries, two medieval Priories and a variety of surface features testify to human activities and intrusion on the landscape.

Associated with the Hills are the famous natural springs which gave rise to the development of Hydrotherapy in the 19th century. Prior to this the Springs had been celebrated for their curative properties but it was not until the development of commercial hydrotherapy that Great Malvern was established as a major tourist resort.[4] In tandem with the water cure came the advocating of fresh air and exercise as a health treatment and the Hills provided the ideal location. Malvern thus enjoyed great prosperity and growth as one of the foremost 19th century spas.

Recognising the importance of the landscape and its conservation, specific AONB provision is made in the Structure Plans of both Gloucestershire and Hereford & Worcester County Councils. These policies are then reflected in the Bromyard and District and the Malvern and District local plans.

The background and effectiveness of AONB designation is covered in detail elsewhere.[7] Suffice to say that AONB has not generally been an effective conservation and environmental protection measure since its inception. The Malvern Hills however are special in that unlike the remaining part of the local AONB and many AONBs elsewhere, there is a body which has a statutory role in administration. The Malvern Hills Conservators exercise independent authority over 11 percent of the total AONB.[8]

There is also a Joint Advisory Committee for the Malvern Hills AONB. This is a coordination measure for agencies with responsibilities and interests in the AONB. Membership consists of representatives from The Council for the Protection of Rural England, Country Landowners Association, National Farmers Union, English Nature, Countryside Commission, Forestry Commission, Conservators, County Councils, Local District Authorities and Parish Councils.[9] Recently revived, it still has to prove its value following earlier abandonment due to lack of cohesion. Between the years 1970 and 1991, the AONB was without a JAC. In April 1994, the JAC announced a draft management plan which included a visitor centre and the appointment of an AONB officer.[10] This followed the publication of the Countryside Commission landscape assessment of the AONB which identified the special character of the Hills and the AONB and the area's national importance.[11]

The 1994 management plan is disappointingly predictable in its nature, reflecting issues and proposals echoed in numerous countryside publications and now part of the conservation culture of the countryside. It identifies particularly the problems of tourism conflicting with planning policies (3.8.13) and the difficulties in promoting the actions proposed (4.4.1). Seen as a precursor to some limited Countryside Commission funding, the plan is inherently weak due to lack of implementation resources. It also lacks pioneering vision, no doubt as a result of wishing to please all agencies involved in its inception. The result is a document that upsets nobody, but in doing so, it can be argued, achieves little.[12] This raises the question, will the Sussex Downs Management Plan, now under preparation, inevitably result in a similar outcome?[13]

The Malvern Hills Conservators were established by an Act of Parliament in 1884 to prevent encroachment on the Hills and commons. The Conservators duties are historically defined as "to keep the Malvern Hills unenclosed and unbuilt on as open spaces for the recreation and enjoyment of the public"[14] Later Acts in 1909, 1924 and 1930, have increased the Conservators' powers to regulate the user and enjoyment of any rights of common. Motor cars, quarrying, encroachment and expanded public amenity provision are all issues successfully dealt with by the Conservators since their inception. They have also acquired further lands over time resulting in present day primary managerial responsibility for approximately 1,100 hectares. The statutory powers given to the Conservators has resulted in particularly effective conservation of an AONB over a prolonged period of time. Land Use Consultants, acting on behalf of the Countryside Commission in 1980, conducted an enquiry into the Malvern Hills AONB management and concluded that the role of the Conservators and their management of the Hills was a "very considerable achievement" The enquiry further noted that the then expenditure of UK pounds 28 per acre p.a. was moderate compared with other areas in public ownership. Visitor impact leading to erosion was observed to be a major current concern.[15]

The power of the legislation under which the Conservators function should not be underestimated. This has enabled the Conservators to challenge the intentions of powerful institutions which, over the years, have cast covetous eyes on the Conservators land holding. Over one hundred years ago the Conservators took on the Malvern Local Board, who believed that they had a right to just over six hectares of Malvern Common required for a public water supply scheme. By January 1890, both sides were in deadlock. Arnold Taylor, Local Government Board Inspector, held an official enquiry into the matter in March. The enquiry found for the Conservators suggesting that only by Act of Parliament could the Local Board possibly pursue their wishes. As a result an important and much needed local water supply project was abandoned.[16] Such was the power of the Malvern Hills Act.

The success in conservation of the Malvern Hills is in contrast to what has happened on the Sussex Downs where building encroachment and urbanisation has been considerable, agriculture has been allowed to transform much of the landscape and tourism has resulted in the location of major enterprises and infrastructure on the Downs. As a result the Malvern Hills are a priceless amenity for both locals and visitors from further afield whereas the Downs are seen by some as a rescue operation at best.

The Conservators are a body of 29 individuals, some directly elected and some nominated. They include representatives from District and Parish Councils, others represent agencies with particular local interests such as Church Commissioners. There is no direct representation from the Countryside Commission or any visitor/tourism agency. The entire Board meets on a monthly basis with a varying number of sub-committees meeting as appropriate. There are generally about nine such sub committees dealing with such diverse matters as Bylaws, Finance, Cafe Tenancies and Land Acquisition.[17]

The absence of representation by a visitor/tourism agency on the Conservators Board results in any liaison necessary having to be carried out by field staff. As a result, the coordination of day to day matters runs into difficulties because of conflicting policies and strategies from above. An example is the Worcestershire Way which at present runs to the boundary of the Hills.[18] The wish of the Countryside Commission/County Council is to extend the path over the Hills as part of the National Long Distance Footpaths programme.[19] As a result the Conservators are considering accommodating the footpath extension, but only in the context of their own policies for visitor access and management, not in the context of a debated and coordinated regional framework. The outcome may not therefore be as perfect a solution to the issues involved as it may have been if coordination were taking place at policy level also.

Funding for the Conservators is through a levy on the local rates. This facilitates the execution of a variety of maintenance and restorative works by a Ranger and team of workmen. The Hills are used for a wide range of recreational uses from hang gliding to walking and the Worcestershire Way terminates immediately adjacent to the Hills. Visitor numbers are estimated to be between 1 - 1.5 millions per annum and this necessitates the provision of various amenities and services, from car parks to grass mowing, to accommodate such numbers.[20]

Visitors in such numbers, coupled with estate management duties, means that policing is an important and necessary aspect of the Conservators operations. Bylaws are implemented to add to the powers of the original Acts, a process regulated through the Home Office. Officers of the Conservators act as wardens and in the event of prosecution, action is taken through the local magistrates courts.[21] A proposed new Malvern Hills Act seeks to enhance the policing provision by, for example, enabling the Conservators to deal with abandoned vehicles more effectively.[22]

Major influxes of unplanned visitors are beyond the policing resources of the Conservators as was shown by the invasion of Castlemorton Common by 20,000 travellers, ravers and curious bystanders in May 1992.[23] Here it became appropriate to join forces with the local police, not only to remove the invasion but to prevent its re-occurrence in subsequent years. This included the securing of High Court Injunctions in 1993.[24] Such actions inevitably raise issues of why the Hills are protected and for the enjoyment of whom? Similar crowds are regularly accommodated on Commons elsewhere to the economic and recreational advantage of the local populace, for example race week on Epsom Downs. The character and noise of the crowds have a distinct resemblance to the Castlemorton tourist invasion but with adequate policing and organisation, negative impacts are minimised to the advantage of all. It is apparent that policing is a significant task for the Conservators, requiring not only financial resources and manpower but also statutory power. Policing implications for the Sussex Downs are discussed in Chapter 12.

The Conservators have been criticised recently on several issues.[25]

1) The secrecy that apparently surrounds their proceedings; their Board meetings are open to the public but this facility has only recently been extended to committee meetings.

2) The financial burden, which is borne by the local community to which they have no direct accountability.

3) Many of their roles are now replicated by County and District Councils, from planning to countryside management.

Awareness of these issues has been heightened by the application by the Conservators for a new Act of Parliament which will, if passed, enable them to build on their lands, a privilege previously denied.[26] Baroness Nicol, speaking in The Lords at the second reading of the Bill, voiced the view that "....the Conservators have sought power to exclude the public and to perform certain other acts which are a negation of their original aims." [27] This has caused considerable public opposition due to the fact that Malvern Hills conservation has been particularly successful since the establishment of the Conservators and the public fear that this may now be jeopardised.[28] In response to the opposition to the Malvern Hills Bill, the promoters, ie the Conservators, have been obliged to amend the proposals to exclude the more controversial powers. In addition, the House of Lords Select Committee has seen fit to recommend further revisions.[29] These include the denial of any facility to build, especially to replace a beacon top cafe, regulating public access under certain conditions, provision of visitor centres but off the hills, endorsing of the inalienable status of the hills and the management of horse riding in a manner similar to Epping Forest.[30] All of these issues have implications for tourism. The important effect of this realignment of the aspirations of the Conservators has been to re-establish the body in a supervisory capacity over a highly protected landscape, with very restricted powers to do anything other than manage the status quo. The final version of the revised new bill is imminent.[31]

The role and activities of the Conservators have many similarities to the Sussex Downs Conservation Board. In particular, many countryside management functions normally carried out by County Councils are carried out by the Conservators. This will be discussed later. At this point it should be noted that no tourism office or Board is represented on either the Conservators or the Joint Advisory Committee. This is in spite of the fact that the Malvern Hills represent one of the prime tourist attractions in the West Midlands.

Unification of Strategies within the AONB Historically the Conservators have acted as an independent body relying on their membership to coordinate the efforts of other agencies. Elsewhere minimal regard was given to AONB status. In order to strengthen the hand of government agencies and local planning authorities throughout the AONB, a Statement of Intent was prepared and published in 1991 by the County and District Councils in conjunction with the Countryside Commission.[32] This document seeks to coordinate planning issues throughout the AONB in line with Government Policy and is seen as a means of strengthening the AONB effectiveness by creating a framework for some grant aid.

Within the Statement of Intent, recreation and tourism is covered in detail. The document recognises three distinct classifications of visitors, local residents, day visitors from further afield and tourists on holidays. These visitors in turn generate a number of problems: traffic congestion, erosion, overuse of sensitive geological and archaeological sites and threats to habitats as they disperse across the Hills. These problems are focussed in the area controlled by the Conservators. Suggestions to reduce the adverse impact include visitor dispersal, particularly to Great Malvern where alternative attractions and accommodation is envisaged. This particular point is commented on by Bennett later in this case study. To date the Statement is seen to have had little impact on tourism policy and management.

The role of the Conservators is outlined in the appendix to the Statement of Intent although the bibliography only cites a 1989 Conservators management plan as a source. The bibliography also cites the Sussex Downs AONB Statement of Intent. This is presumably the 1986 document prepared by ESCC & WSCC and which has been used as a role model.[33]

The Malvern Hills District Council is a key activist in the promotion of tourism in the area. The Council administers its involvement through a Tourism and Leisure Sub Committee. The responsibilities of the Sub Committee include a number of specific areas including local recreation facilities such as the swimming pool, participation in the Tourist Information Centre in conjunction with Heart of England Tourist Board and the Recreation and Tourism Officer and department. These in turn operate an active conference marketing facility as well as orchestrate the general promotion of tourism.

A number of identifiable problems exist within this arrangement.

1) Historically the Tourism Department of the Council has suffered lack of credibility due to the former officer allegedly taking a course of action which resulted in his imprisonment!

2) There is no strategic policy planning for tourism although the latest Tourism Officer accepts that such a document is essential before appropriate tactical planning can take place.[34] A project was subsequently been launched with the Heart of England Tourist Board to prepare proposals for Tourism Strategy and Planning; although the final report is still awaited, the draft is under consideration.

3) Pressure on budgets renders the tenure of the present Tourism Dept employees as under threat. In June 1993 the Council secretariat prepared a report for the Tourism and Leisure Committee to consider. This recommended budget cuts for the Tourism Dept. from the former level of UK pounds 185,520 to UK pounds 80,000. Such cuts would not only mean a substantial curtailing of activities and staff but would also place greater reliance on other agencies, particularly the Tourism Association for proactive tourism development.[35]

In 1992, following public pressure, the Tourism and Leisure Sub-committee called two public meetings to debate openly the development of tourism in The Malverns. Resulting from this, a steering committee was formed to look at the possibilities and advantages of formalising a Tourism Association. The steering committee comprised local interested parties on a volunteer basis and in due course this gave rise to the The Malvern Spa Tourism Association which the author chaired.

The Malvern Spa Tourism Association Committee membership included informal representatives of the local Council, Conservators, Hotels and Restaurants Association, Bed and Breakfast Consortium, Malvern Museum and the Civic Society as well as individuals serving through personal interest. During the first year of the Association a number of problems became apparent.

1) The low resource base, dependent on membership fees and time given freely meant that the Tourism Association was restricted in its activities.

2) The lack of an overall Tourism Strategy and conflicting opinions from various town factions interested in tourism resulted in a number of generally valuable initiatives being dependant on individuals enthusiasm rather than collective endeavour to bring to fruition. In certain instances, lack of overall strategy resulted in rivalry between the factions giving rise to misplaced effort.[36]

Bennett Report In order to bring about a sense of order to the development of the activities of the Association, in the summer of 1992 the University of Birmingham provided a postgraduate team to conduct an audit of tourism resources throughout The Malverns. This was followed by a detailed evaluation of Tourism in the Malverns by Bennett, one of the original team from the University.[37]

Bennett identifies the opportunities and the problems of organising for tourism in The Malverns from an informed, independent stance. As a critical analysis it is organised in two main parts. First he elucidates the latent capacity for tourism and then reviews the agencies that are in a position to influence substantially tourism development. Both the identified absence of a coordinated approach to targeted tourism opportunities and the implementation and organisational problems are pertinent to the organising and managing of tourism on the Sussex Downs.

Five themes for future development are discussed by Bennett. These are health, heritage, local culture, an events centre and activity holidays. Issues raised within the discussion include opposition by residents, a lack of a unique proposition giving rise to competition from elsewhere, capital investment in infrastructure and general coordination.

In order to develop tourism, Bennett notes that existing tourism resources in the area must be identified, as has been done by the earlier audit carried out by the University team. In addition however the expressed and latent demand for the type of tourism experience that Malvern may offer needs clear identification through research. This would then enable development initiatives to be tuned to precise target markets. Applying these considerations to the Sussex Downs underlines the importance of the Visitor Study carried out for this thesis.

A major problem for Malvern in developing tourism is the existence of various factions who are able to influence the quality and nature of any tourist development. Many organisations exist who are able to voice opinions and influence decision making. Often the opinions expressed are, arguably, out of proportion to the validity of their reasons for controlling the process concerned, such opinions being based on interests vested in conservation rather than economic generation.

It is noted that legitimate concern is felt about issues relating to the quality of life in Malvern. Tourism impact can be detrimental but with skilled management there are many benefits to be had. The report notes that tourism agencies need to be sensitive to such issues but that management action must be realistically based. For example an alternative attraction off the Hills will only draw people from the Hills if it provides a similar or improved experience to the one sought by visiting the Hills. More knowledge on tourist motivations for visiting the area is essential.

The difficulties of coordinating the activities of various agencies in The Malverns, both commercial, elected and non commercial, is identified. The preparation and common agreement on overall policy statements and intent is essential in order to ensure that all interests work towards common goals. This in turn provides a unified framework for individual organisations to pursue their own remits.

The prediction that there will be a population profile change leading to more 45-60 year olds is seen as beneficial to Malvern. There is a shortage of attractions for young adults. Malvern may well be best suited to accommodating the needs of the expanding older age groups. In particular short stay holidays of up to three nights are important expressions of local demand.

Bennett concludes by indicating that if Malvern is to progress it needs to harness the resources of the public and private sectors without compromising discrete objectives. Joint development initiatives, not jeopardised by rival factions and pressure groups, will enable the benefits of tourism to be maximised whilst minimising the adverse impacts and costs.

Heart of England Tourist Board Report This substantial report was prepared for the Malvern Hills District Council by the HETB Development Dept. and is available in draft form as A Strategic Plan for Tourism in Malvern 1993-1997.[38]

It carries out a thorough review of tourism in The Malverns and assesses market prospects. The report then goes on to consider a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats analysis for tourism followed by a review of key issues. The national and regional implications are reviewed and this leads to a strategy and proposed action programme for Malvern. Working in partnership is a theme throughout the report and inevitably the report has had to consider the budget cuts outlined earlier in the District Council expenditure on tourism.

There are a number of issues that are presented which have relevance to the Sussex Downs.

1) Malvern has at the moment three key selling points, the Hills AONB, the Water Heritage and the Arts. These are supported by a range of facilities including the Winter Gardens, accommodation etc.[39]

2) There are various organisations with an interest in tourism, these organisations lack a clearly defined role and thus confusion exists.[40]

3) The expanding market for short breaks means that Malvern is ideally suited to capture a substantial slice of the market.[41] In particular the strategic location makes it a useful centre for visiting elsewhere.[42]

4) The town has a deteriorating appearance, there is over supply of bedspace with deficiencies in quality and there is a lack of attractions suited to inclement weather.[43]

5) A disjointed and apathetic approach exists to tourism coupled with a lack of vision.[44]

The report proposes a general development of a number of distinct tourist products with relevant upgrading, promotion and monitoring. These relate to the key areas in 1) above. The budget cuts have a direct impact on the ability of the District Council to support the generation of tourism and a combination of contracted services and focus of effort are proposed to ameliorate the effects. Separately, a local proposal for a marketing bureau is under consideration by the Council.[45] This has relevance to the report which discusses the development of the Tourism Association as a means of uniting trade and community interests. The need to create partnerships is underlined and again reflects the strength to be secured from united effort when individual agencies are weak.

The report largely omits the nearby Three Counties Showground as a tourist attraction but reflects many of the other points previously made by Bennett.

Tourism Officer. The development of tourism in The Malverns has centered on the Council's Tourism Officer and his department. Budget cuts have resulted in the future of this department being under question, as has already been noted. The Council announced a working party on tourism in the latter part of 1993 and a District Tourism Board was agreed in December of 1993. By March 1994, the Tourism Association was bemoaning lack of action.[46] Allegedly also in March 1994, it was announced that the latest Tourism Officer had been dismissed supposedly due to a contentious and disputed alleged misuse of funds. The Council were unlikely to replace him.[47] This was a similar plight to that of an earlier Tourism Officer who allegedly ended up in prison.

The effect of this action was to add a further layer of disorganisation to an already chaotic, uncoordinated situation and to jeopardise any efforts to bring about order as a result of the Bennett and HETB reports.

The District Council, in 1994, announced that they intended to appoint a new marketing and tourism officer.[48] This followed the attempted initiative, by the Council, to set up a Tourism Board comprising all tourism interests, as an alternative to the funding of a Tourism Department by the Council.[49] The burden that this would place on "voluntary effort" resulted in the idea being received with limited enthusiasm.

Summary. Reviewing the status of Tourism Development in The Malverns indicates that matters are in disarray. No single minded common endeavour has been achieved and this could arguably be attributed to the lack of a structure within which such an endeavour could be orchestrated. The Tourism Association has identified the problem as a result of its joint work with the University of Birmingham, but due to lack of resources is limited in its ability to lobby decision makers. Following the further disruption of the Council Tourism Dept, there was a mass resignation of committee members of the Tourism Association in 1994, including the latest chairman who inherited the chair from this author. As a result the Association is now effectively defunct. Any move to establish order and forward direction is likely to be long and slow, although the Bennett report has been drawn to the attention of the Heart of England Tourist Board, who have considered the findings in the context of their now apparently redundant report.

Within Malvern there is a powerful lobby which resists any economic development, possibly because they believe that they have no vested interest in enterprise, other than coping with the negative effects. This reflects the opinions of the older population who see Malvern as a retirement locality. Bennett identifies this major inertia, which manifests itself through the Civic Society, The Conservators, Malvern Museum, The Councils, etc. The dispersion of decision makers through a variety of bodies enables such views to prevail by intransigence and by default. Recent press editorial has established this in local culture as the Malvern-factor.[50] As a result Malvern loses the ability to launch coordinated initiatives which could have a major impact on tourism development and in turn, forsakes the economic benefits that such effort would yield.

The response to such accusations is generally that tourism brings negative impacts which are unwanted. This ignores the fact that Tourism can be a positive force in the prosperity of a community and in furthering conservation ideals as illustrated in the Dartmoor case study. This leads to the hypothesis that it is the management of tourism which is crucial to the type of impact tourism has, rather than tourism itself. For management to be effective however it must have common purpose voiced through an appropriate organisational structure; a point that will be now addressed for the Sussex Downs in the next chapter of this thesis.

A further development of the argument is that without adverse change, resulting from enterprise including tourism, there is no need for conservation. A course of action, reflecting this premise, can be adopted as the route of least resistance, if economic prosperity is assured through historic savings such as pension funds or accumulated capital. A counter argument is that change is inevitable and that the only debate is in which direction it moves. Such philosophical issues are raised later in this thesis.

Unlike Dartmoor, where an operating structure has been created for developing responsible tourism, Malvern has no unified structure for Tourism although tourists continue to frequent the locality in significant numbers by default. Therefore there is no forum for determining common objectives and strategies. As a result management is ineffective. Tourism is also low down on the priority list of bodies who could well be major players in a Tourism initiative. The outcome is typified by its disharmony.

Footnotes:

[1] Malvern Advertiser, 1883, 11 Aug.

[2] Weaver C & Osborne B E. 1994, Aquae Malvernensis, Cora Weaver, Malvern, p.iii.

[3] Mitchell G H. Pocock R W. & Taylor J H. 1962, Geology of the Country around Droitwich, Abberley and Kidderminster, Inst. of Geological Sciences, HMSO.p2.

[4] Weaver C & Osborne B E. 1994, p.141.

[5] Winsor J. 1987, 6th ed. What to see in Malvern, Winsor Fox Photos, Malvern.

[6] Countryside Commission, 1992, Directory of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, CCP 379, p103.

[7] See Chapter 2.

[8] Countryside Commission, 1992, p103-107.

[9] Russell P. 1993, Letter to this Author, Hereford and Worcester County Council, 2 Feb.

[10] Malvern Gazette, 1994, "Managing these Hills", 1 April.

[11] Landscape Design Associates, 1993, The Malvern Hills Landscape, Countryside Commission, CCP 425.

[12] Hereford and Worcester County Council, 1994, The Malvern Hills Management Plan, consultation draft, March.

[13] Sussex Downs Officer, 1994, Sussex Downs Consultation Paper, draft text, SDCB, Dec.

[14] Hansard, 1993, Malvern Hills Bill, House of Lords, 8 March, p875.

[15] Hurle P. 1984, The Malvern Hills, 100 Years of Conservation, Phillimore, Chichester, p114 & 117.

[16] Malvern Advertiser, several editorials between March 1889 and March 1890; Weaver and Osborne, 1994, p190.

[17] Hurle P.1984, p124.

[18] R. Hall-Jones, Conservators, 1993, personal communication.

[19] Countryside Commission, 1989, Paths, Routes and Trails: Policies and Priorities, CCP 266.

[20] Parsons A J, 1981, The Malvern Hills Conservators, typescript.

[21] R. Hall-Jones, Conservators, 1993, personal communication.

[22] Clerk of the Board of Conservators, 1992, A Bill to amend certain Enactments relating to the Malvern Hills Conservators and the Management of the Malvern Hills, Malvern Hills Conservators, Malvern. see Clause 22.

[23] Daily Mirror, 1992, "Hippy Days are Here Again", 26 May, p9.

[24] Malvern Gazette, 21 May 1993, "Message is : Stay Away from Here", p1 also "This Must Not Happen Again", p6.

[25] Malvern Gazette, 1993, "Are the Conservators Out of Date?" Jan 15, p 6.

[26] Clerk of the Board of Conservators, 1992.

[27] Hansard, 1993, p876.

[28] Malvern Gazette, 1993, "Opposition Mounts to Conservators Bill", Jan 15 p1.

[29] House of Lords, 1993, Malvern Hills Bill - Minutes of Evidence, M S Kempt, chairman, 26 July.

[30] HMSO, 1990, City of London (Various Powers) Act, 9,10.

[31] Malvern Civic Society, 1994, "The Malvern Hills Bill" Newsletter, March, p3.

[32] Countryside Commission & H&W CC. 1991, Malvern Hills AONB Statement of Intent, Countyside and Conservation Dept., Hereford and Worcester County Council.

[33] WSCC/ESCC. 1986, Sussex Downs AONB Statement of Intent, WSCC.

[34] Recreation and Tourism Manager, 1992, personal communication.

[35] MHDC, 1993, "Report of the District Secretary", Tourism and Leisure Committee agenda, 30 June.

[36] Malvern Spa Tourism Association, 1993, Minutes of AGM, item 7, 12 Oct.

[37] Bennett M A. 1992, A Critical Analysis of the Tourism Development Potential of the Malvern Hills, Centre for Urban and Regional Studies, University of Birmingham.

[38] HETB, 1993, A Strategic Plan for Tourism in Malvern, draft for consultation, Development Dept.

[39] HETB, 1993, see p21.

[40] HETB, 1993, see p28.

[41] HETB, 1993, see p32.

[42] HETB, 1993, see p41.

[43] HETB, 1993, see p40.

[44] HETB, 1993, see p42/43.

[45] Hall-Jones R, 1993, Marketing Bureau for Malvern, typescript, 1st July, considered at Tourism and Leisure Committee, MHDC, 19 July 1993.

[46] Weller P. 1994, Committee Meeting Notification and Covering Letter, to Tourism Association committee members, March.

[47] Howells N. 1994, "Tourism Manager Sacked", Malvern Gazette, 18 March; "Tourism Officer May Not Be Replaced", Malvern Gazette, 1 April.

[48] Malvern Gazette, 1994, "Can Malvern Do More For itself?" 19 Aug. p6.

[49] Crooks J, 1994, "New Board to "Sell" the Area", Malvern Gazette, 29 July, p4.