|

|

This chapter details the first of two case studies. The particular value of the case studies is that they highlight the importance of structuring for tourism and the status that should be afforded to conservation measures. These issues are considered further in subsequent chapters. In this Dartmoor Case Study, a number of detailed local reports pertinent to tourism and the National Park have been used as a general reference source.[2]

Background Dartmoor National Park (NP) was designated in 1951.[2] It was the fourth UK Park to receive designation and now comprises an area of 94,500 hectares. Approximately 30,000 people live within its boundaries and 10 million people visit Dartmoor each year.[3] Within this the NPA owns or controls directly only 1330 ha (1.33 sq.km.) of land, representing about one point four percent of the total. This reflects the position of U.K. National Parks generally, which are not seen as land owning bodies. The first National Parks were in the USA and, as early as 1832, 1,000 acres of land with hot salt springs were reserved in Arkansas.[4] Unlike American Parks however, British Parks are not owned by the state and this is seen as a weakness to pursuing conservation ideals. Land ownership remains in the hands of a wide variety of individuals and institutions who seek other benefits from their holdings. When the first British Parks were designated following the passing of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act in 1949, reliance was therefore placed on planning as the controlling force rather than ownership or direct statutory regulation.

In the first decade of British Parks, it is recorded that a major concern was the continued pressure on development particularly statutory bodies who sought to create reservoirs, power lines, wireless masts, commercial forestry etc. In addition, the blurring of local landscape identity was causing concern as buildings, street furniture and man's general intrusion into the landscape took a similar form whether it be in the far north or the furthest south. Traffic management was a key issue, not only the avoidance of trunk road traffic through the Parks but also the reluctance of Dartmoor tourists to leave their cars thereby causing vehicular honeypots. In the 1950s, restricted access was considered together with alternative public transport on a park and ride system. It was also noted that improvements in public rights of way and visitor facilities generally would be advantageous to visitor management.[5]

In the 1970s, similar issues continued to cause concern. Bell summarised the principal problems that the Dartmoor National Park was experiencing which had a direct bearing on recreation and the environment. These included, as well as general visitor impacts, communication masts, new roads precipitating increases in cars, aerial disturbance through aircraft, water supply projects, commercial afforestation, agricultural intensification, speculative building, mineral extraction and general traffic pollution. Stringent measures were considered imperative if the influx of motor vehicles was to be contained, such measures included the proposed reopening of railways and provision of other public transport.[6]

Many of these problems are familiar to the Sussex Downs today and the experience of Dartmoor in attempting to deal with these issues is invaluable as a case study for the Downland.

The Park now has in excess of 40 years of experience upon which to draw. A key aspect of the operational framework within which policies and management decisions are made is that experience has shown that the attempt to maintain quality has to be by regulation. As part of the development of this approach, a new National Parks Act is anticipated during the next year or so together with other supporting measures. With Dartmoor this includes the designation of the Park as an Environmentally Sensitive Area. This has been as a result of the NPA working with the Countryside Commission and English Nature.

The 40th anniversary of the Park prompted the publication of a second major review of progress and planning in 1991. This provides a forum for preparing and agreeing a five year projected plan. In addition a Local Plan is now in draft form serving to supplement the County Structure Plan for the Dartmoor Park.

The National Park Authority (NPA) is Devon County Council which in turn delegates powers to a National Park Committee. Funding is largely by the Dept of the Environment through the Supplementary Grant (75 percent) and the Rate Support Grant (16 percent). The NPA is the local planning authority and can influence agricultural change through the grant notification scheme. This enables alternative management agreements to be negotiated where undesirable agricultural change is intended.[7] In order to further strengthen the role of Park Authorities in managing change, the Government has now accepted the recommendations of the National Parks Review Panel Fit for the Future in which the establishment of Independent Authorities for National Parks are the most significant proposal. Legislation to this effect, albeit delayed, is now at committee stage and expected to pass through parliament in due course, with a time lag for implementation of probably one year.[8] This will move power from the County Authorities into the revised Park Authority.

Another important aspect of the expected new legislation will be the broadening of the conservation of the landscape provisions. This will extend to archaeology, wildlife and cultural heritage. The provision of recreation will be qualified in that National Parks will be for quiet enjoyment. The third aspect will likely be some provision for the social and economic well being of the local communities.

The Dartmoor National Park Authority Committee comprises 11 members appointed by Devon County Council, 7 members appointed by the Dept of the Environment and 3 members from District Councils. It is important to note that the Tourism Board is not represented at this level and this is one reason why the regional initiatives for tourism are particularly important.

The prime landscape which epitomises true Dartmoor is perceived to be healthy heather and undamaged grass moor. An essential characteristic of this landscape is the perception of openness implying a freedom to roam for the visitor. Large tracts of Dartmoor therefore give this impression although on closer scrutiny much of the land surface is fenced and enclosed.

Landscape and access improvement is taking place as a result of a variety of initiatives. The commons are being improved by the management of riding and pony trekking. In addition management agreements are providing for conservation of key areas and improving public access. Heather restoration is seen as an important aspect of maintaining the visual landscape and a variety of measures are being implemented to further this consideration. Grants from MAFF are being effective in the restoration of walling and hedging which are not normally financially viable boundary policies for farmers. Tree planting, boundary improvements and rights of way schemes are actively pursued particularly in the upland and woodland landscapes.

Work on conserving the built environment includes detailed surveys of buildings within conservation zones as well as securing more architectural data on listed buildings. English Heritage in conjunction with local Councils is extending the grant eligible number of buildings. This work is supported by environmental enhancement initiatives. For example the village green at Lustleigh was kerbed in granite to avoid vehicle damage and much work is underway to remove overhead cables.

Extended research on the archaeological landscape is enhancing the knowledge of significant sites and new prehistoric sites are being identified. This work is supported by new scheduling of ancient monuments by the English Heritage Monuments Protection Programme. New guides are available detailing the archaeological heritage. Financial support for much of this work comes via English Heritage.

A substantial proportion, 36,423 ha nearly forty percent, of the total National Park area is common land registered under the Commons Registration Act 1965.[9] This is an important visitor resource. Prior to 1985, public access was by means of unchallenged trespass. A unique piece of legislation, The Dartmoor Commons Act 1985, formalised the right to roam as well as making provision for the management of the right of common. Under the Act a Dartmoor Commoners Council was created to manage use of the commons for livestock. In addition the Park Authority secured powers to manage visitor impact on the moor. This pioneering legislation has resulted in a formalising of the commons as both a public amenity and as an agricultural resource.[10] This triumph was not easily won however. Negotiations for legislation commenced in the early 1970s with a Bill first presented to parliament in 1978. Seen as a possible model for national commons legislation, an issue upon which Government was and continues to be loath to act, the Bill fell in the House of Commons (ironical pun) in 1980.[11] Such legislation is indicative of how commons can provide a valuable and secure land holding with public access, an issue which will be discussed in the context of the Sussex Downs.

Landscape assessment is now recognised as an important monitor of change to the visual environment within the National Parks. The Countryside Commission comment on the relevance of landscape to visitors "One view that is currently emerging is that there may be a need to consider the public as "consumers" of landscape, introducing the idea of market segmentation in recognition that different groups of people have different tastes and preferences".[12]

The Countryside Commission has commissioned a major landscape change evaluation for all National Parks with the objective of preparing statistical and mapped information on the extent, distribution and change over time of a wide range of land cover features. Landscape monitoring is now therefore ongoing on Dartmoor as a result of the Monitoring Landscape Change in National Parks project which completed its latest audit in 1991.

Comparisons with mid 1970s and 1980s data has given a temporal measure of change. It identifies losses or gains in such features as hedges, walls, woodland, scrub, grass moor etc. From the audit it is possible to establish loss of, for example, hedges or a gain in fences. In Dartmoor this amounted to 118.5km. and 32.4km. respectively. The data enables comparisons between Parks and within Parks to be made. It therefore provides a measure by which conservation effectiveness and agricultural change can be measured and compared with elsewhere.[13]

In view of the high value of such data, the SDCB are initiating such an assessment programme in conjunction with the Countryside Commission.[14] First drafts suggest that this is a qualitative assessment rather than quantitative, replicating much of the opening chapters of this thesis.[15] This could well provide a continuation of the work of Stamp, published in 1942 which looked at the history of land utilisation in Sussex in considerable depth.[16]

Crime There has been some evidence of theft of artifacts from Dartmoor, particularly stone troughs and items suitable for garden ornamentation. This particularly detracts from the environmental enhancement initiative. Crime has also extended into animal rustling and again this threatens the traditional grazing.[17]

Policies for enjoyment are categorised in the Second Review Plan under the following general headings: recreational strategy, traffic and site management, general access on foot, horseback and pathway, special pursuits and events, and tourism. Much of the second review plan is replicated in the Local Plan, simply because the same considerations apply. The general emphasis with regard to tourism is to locate new enterprise outside the Park core zone. The exceptions are enterprises which enhance the intrinsic qualities of the Park. There are several provisions which are cited as particularly important in the Local Plan. One of these is the rejection of any proposal which is likely to generate damaging recreation, included in this is noise and generally disturbing activities. This planning policy, known as TM9, clearly moves the National Park away from any notion of a public open space suited to almost any outdoor activity. In addition it limits the activities of riding schools or cycle hire companies who may well create substantial impact on the landscape if allowed to expand to meet demand. Camping and caravanning is also seen as best sited outside the Park perimeter.

In line with Government policy, public enjoyment of the Park is conditional upon the natural beauty remaining unimpaired for future generations. This is implemented through policies to disperse car parking, route planning for traffic, location of attractions away from the NP core zone, opening up further public access (an example being the re use of old railway tracks for recreation), the planning of mass events to minimise impact and the avoidance of inappropriate developments such as golf courses.

Traffic Planning Following a detailed traffic survey, a management strategy is being drawn up by the County Highways Dept and the NPA.[18]

Tourism and recreation It is generally accepted that the relationships between conservation, recreation and the local economy are particularly strong. The landscape and conservation aspects of Dartmoor provide a basic resource for the tourism industry. The three key tactical elements that are pursued in order to responsibly use this resource are:

1) the development of commercial tourist interests outside the National Park area,

2) the development of a central booking agency for accommodation for the greater region, and

3) the development of visitor interpretation facilities at Princetown.

This approach supports an underlying marketing philosophy which is based on the conservation of the core product which is then made available to those wishing to use it. It is not modified to exploit the visitor needs. This neutral stance is developed in greater detail in Chapter 10 in the context of the Sussex Downs.

In accordance with 1) above, visitor recreation is encompassed in the regional approach, extending beyond the bounds of the National Park. This manifests itself through the Dartmoor Area Tourism Initiative.

An important differentiation is made in all Dartmoor National Park's published texts in that Tourism is treated as different from recreation. Interpreting this differentiation, tourism is seen as a commercially exploited economic process whereas recreation is seen as visitor hosting as well as leisure time activity of local residents. This differentiation I suggest is partly attributable to the segregating of Tourist Board/economic activity input from the NPA and is thus an organisational problem rather than a valid separation for planning considerations. The regional initiative overcomes this problem. The relationship between tourism and recreation on the Sussex Downs has been discussed in Chapter 4 and it is proposed that the two are inseparable for the purposes of this study.

Community Development and Tourism is steered by the Devon County Structure Plan which now rolls forward to 2001. Underpinning this is the NPA Local plan. Recently there has been a strengthening of the policy on development control in the National Park by the adoption of the presumption against development, except where this is necessary for economic, social or enhancement considerations. Further powers are divested in the planning authorities as a result of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and the Planning and Compensation Act 1991. In particular the Authorities ability to deal with infringement of planning policies is enhanced. A recent change in procedure now means that planning proposals are initially submitted to the NPA rather than District Councils. This has been a welcome revision to the previously adopted procedures.

Visitor numbers are difficult to define. Total day visits are estimated at 8.73 millions for 1989 although not encompassing the broad definition of tourists as determined for this thesis. There has been a steady increase in numbers using visitor Information Centres since 1985. In 1991, 261,477 were recorded. Sales of publications and other income is now seen as an ever increasing and important aspect of the Information Centre's role and funding provision. Similarly activities such as organised guided walks present low level economic opportunities for visitor hosting.

Walking is by far the most popular visitor activity with picnicking and sedentary pursuits taking an increasingly less significant second and third place respectively. Nearly eighty percent of visitors had been before. Buckfast Abbey is the most popular attraction with 551,413 visitors in 1989.

Visitor research has been developed to a high degree in the Dartmoor National Park. A major visitor survey was carried out in 1991 by the NPA. This comprised peak hour visitor counts at 80 selected sites across the National Park with the distribution of self completion questionnaires to each vehicle. 15,500 vehicles were counted and 6,000 questionnaires returned. Supporting this exercise was a traffic counter survey to give an estimate of overall visitor numbers. The survey was deliberately styled to give comparative data with earlier surveys done in 1975 and 1985.[19]

The questionnaire and methodology produced valuable, quality data with high cost efficiency. This type of approach to the securing of behavioural and demographic data of visitors provided useful guidance in the preparation and implementation of the Sussex Downs Visitor Survey for this thesis.

Visitor data research is being extended in 1994 with an initiative to implement a coordinated survey through all National Parks. This is a cordon and site interview research exercise.[20] The Sussex Downs could well benefit from participating in such nationwide surveys in the future although initial results from Parks participating suggest that definitions of tourism and methodology would not pick up the high proportion of local use seen as important on the Downland.[21]

Finance for the year 1991/2 amounted to a gross outgoing of UK pounds 2,649,208 (100%), included in this was:

Conservation 928,329 35%

Planning 262,048 10%

Information services 442,757 17%

Recreation 370,067 14%

Management & Admin. 417,620 16%

Offsetting this outgoing was an income of UK pounds 1,795,208 leaving a County Council net contribution of UK pounds 854,000.(32%)

By 1994/5 it is expected that expenditure will rise to UK pounds 3,122,120 (100%) which will include:

Planning 271,910 9% -

Information services 358,050 11% -

Recreation 499,900 16% +

Management & admin. 409,530 13% -

The symbols indicate whether the forward projection anticipates an increase or decrease in total expenditure by heading as a percentage of grand total expenditure compared with the 1991/2 actuals. It can be seen that percentage expenditure on conservation and recreation will increase. Other areas will decrease.

The figures projected for income are not compatible with the 1991/2 actuals and have not therefore been directly compared.

Throughout this evaluation of the key tourism and recreation issues within the National Park is the desire to locate certain activities beyond the boundaries of the Park. This policy is fundamental not only to the subsequent landscape conservation and visitor management endeavors of the NPA but also to the economic and social development of surrounding districts. The advantages are numerous, but in particular locating in this manner enables the core area to be sustained and nurtured as a conserved landscape, with a visitor management that minimises adverse tourism impact. The outer zone is then able to develop economically and socially to accommodate the visitor potential to advantage. To achieve this however an organisational structure was required.

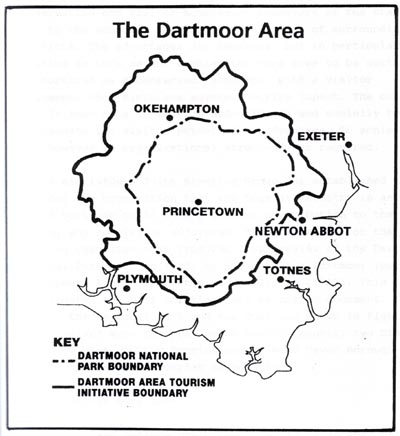

In the mid 1980s a Joint Steering Group was established to consider the proposition that the tourist industry in and around Dartmoor could make a greater contribution to the local economy and to visitor enjoyment. The initiative for the steering committee came from the first review of the Dartmoor National Park Plan in 1983. By April 1986 a Dartmoor Tourism Development Action Programme was published (TDAP). This consolidated the DATI thinking into an action document. The area of the National Park and the TDAP are shown in Figure

8:1. Involved were the NPA, Devon County Council, two District Councils, West Country Tourist Board, West Devon Borough Council and Dartmoor Tourist Association.

The objectives were to:-

i) identify and enhance basic resources ie landscape, heritage and culture,

ii) to identify and develop opportunities for tourism to add to the local economy, and

iii) to minimise adverse effects on local communities.

The basic resource was seen as Dartmoor National Park. A coordinated action plan was then prepared which summarised a range of activities under several headings: environment, recreation opportunities, interpretation, accommodation, value for money, information and marketing. The strategy being followed was the segregation to the perimeter zone of development not sympathetic to the intrinsic qualities of the National Park. Responsibility for the projects was allocated to member organisations.

The success of this initial scheme, tempered with experience gained in its implementation, led to a second TDAP initiative replacing the former in 1991.

This new initiative was wider in its range of participatory members and in its activity programme. At its core are the organisations represented on the earlier TDAP. In addition the 1991 TDAP included commercial interests, particularly the Duchy of Cornwall as well as The Rural Development Commission, Countryside Commission and local industry and other bodies. Specific projects also involve the Area Museums Council, South West Arts, English Heritage and the SW Council for Sports and Recreation.

One key element in the new TDAP was the coordinating and consolidating of funding for the overall projects. It is expected that the three year programme will cost out at about UK pounds 450,000. A steering committee, made up of representatives of funding bodies manages the allocation and expenditure of the financial resources. For practical purposes, this is divided into a project group and a marketing group. The Tourism Development Action Programme team becomes the operational agency for carrying out certain of the tasks, usually in conjunction with DATI steering committee members own workforces. The team comprises four employees based at The Duchy Buildings, Princetown. Additional funding is sought for particular projects from outside agencies such as the EC, the operational structure being adjustable to accommodate variations in the programme.

The thrust of the initiative is similar to the earlier TDAP but is reinforced by such refinements as a published interpretation policy. Key areas to which attention is focussed include interpretation, appropriate marketing, public transport, farm diversification, sustainable tourism, management of tourism impact and a monitoring facility.

In the 1993/4 detailed programme, precise allocations of monies enables the operatives to focus their attention accordingly. In addition a variety of unfunded activities are considered important including liaison with other field workers like farmers. The Area Tourism Initiative is additional to the member agencies own internal activities and therefore inter agency liaison is essential at all levels.

The advantages of the DATI overall can be summarised as follows:

1) Release of funds to achieve a coordinated effort where overlapping responsibilities exist.

2) The depopulation of tourists from the core area which is then more easily protected and conserved.

3) The concentration of economic activity in the perimeter belt where it is particularly needed as part of a rural development policy.

4) A mechanism for agreeing common objectives between agencies over a region approximately twice the size of the National Park.

5) The pooling of information resources and planning skills amongst all member participants.

6) An improved visitor experience in the conserved core are.

7) Added visitor facilities and variety of experience in the peripheral zone.

8) A coordinated policy to redistribute visitors to where they can best be appropriately accommodated.

9) A single agency dealing with visitor related projects ranging from bus route planning to volunteer working parties.

10) A more balanced input at higher level than achieved by the NPA, for example the TDAP includes the Tourist Boards and some commercial interests.

11) Transport and traffic movement can be coordinated over a wider area.

12) In addition, the NPA can pursue a neutral marketing stance towards tourism. This is developed further in Chapter 10.

There are however dangers in this approach also.

1) The image of the core zone is very much a matter of personal perception. It comprises a complex mixture of tangible and intangible factors as has been discussed earlier. By preserving the core zone by a neutral marketing stance and by "conservation" measures, the landscape is moulded to conform with the idealised vision. Such an idealised vision however is a product of individual value systems, experience and perception. The result is that those who have the power, determine how the landscape should be moulded. This means that it can become an artificial construct fashioned by middle class values. No longer is it a working landscape in the traditional sense, instead it is the realisation of a fantasy land. Some would argue that the route through this particular problem would be to let nature take its course, unhindered by human intervention. This however ignores the fact that for thousands of years people have relentlessly modified the landscape to suit their needs. Human intervention is necessary to perpetuate anything like the existing or any idealised notion of how it should be.

2) The second area where the neutral marketing approach runs into difficulties is in the human geography. Any aim to promote a vision of how a landscape may look and function has to accommodate the inhabitants and agriculture, the backbone of the local economy. This is not a process of selection where certain people are privileged but others not. Dartmoor has to accommodate the needs of the existing communities and this means low price starter homes, council housing, modern health centres, sewage works, garages, street lighting and all of the accoutrements of modern living. The inhabitants cannot be realistically expected to be "actors on a rural stage" [22] and undergo rural deprivation or economic hardship in the interests of pursuing a notion of an idealised landscape that cannot function as a living landscape.

In spite of these reservations, the inner and outer zone strategy and marketing philosophy is proving to be an effective approach on Dartmoor. With the involvement of so many different agencies a further danger is that the organisation becomes top heavy with controlling bureaucracy. The essence of its success however lies in the premise that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Communication and networking are essential skills for the four employees carrying out the work programme. In addition the top down approach of the TDAP is necessarily balanced by the field workers of the individual member organisations making major contributions to the strategies and planning of appropriate work programmes. In this way the interests of those "on the ground" are represented and coordinated into the overall thinking. The application of such thinking to the Sussex Downs will be shown to be of particlar importance.

Illustrations:

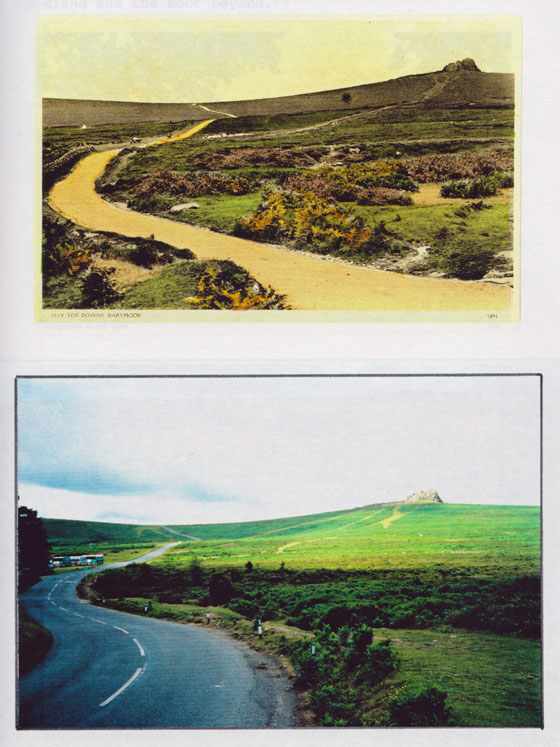

1) Hay Tor in the 1920s and today - one of Dartmoor's most famous honey pots - only the vehicles give a clue to the 70 years age difference between these two postcards.

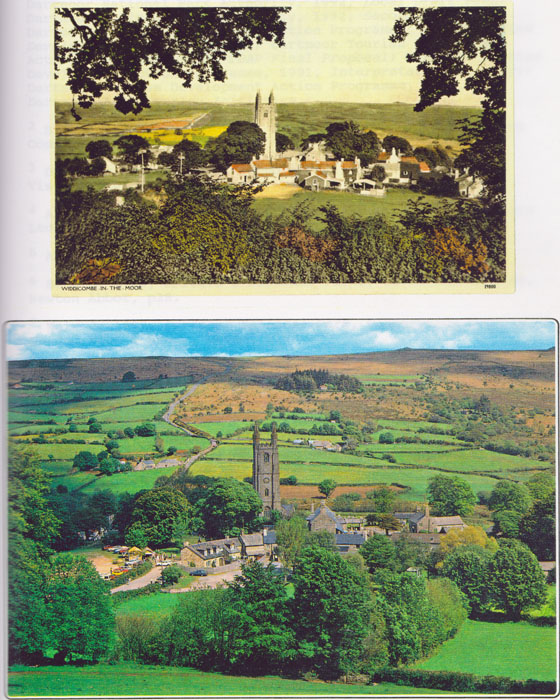

2) Widdecombe 1920s-1990s - more than a quarter of a million people visit this village of just 60 permanent inhabitants every year, in spite of this it has changed little over 70 years.[23] Taylor in Hoskins identifies the complete medieval landscape preserved, with village and church surrounded by farmland and the moor beyond.[24]

[1] Dartmoor National Park Authority, Parke, Bovey Tracey and Dartmoor TDAP staff, Princetown, 1993, personal communications; Dartmoor Area Tourism Initiative, 1992, Proposed Work Programme and Budget, 1993/4; Dartmoor National Park Authority, 1992, The work of the Authority, 1991/2; Dartmoor National Park Authority, 1992, Local Draft Plan; Dartmoor National Park Authority, 1992, Second Review; Dartmoor Tourism Development Action Programme, 1986, Tourism Develpment Action Programme; Dartmoor Tourism Development Action Programme, 1991,TDAP Final Proposal; Dartmoor Tourism Development Action Programme, 1991, Interpretation Strategy; Dartmoor Tourism Development Action Programme, 1991, The Dartmoor Area Tourism Initiative.

[2] Blunden J & Curry N. 1990, A Peoples Charter, Countryside Commission. p100.

[3] Dartmoor National Park Authority, 1993, "Well Worth a Visit", The Dartmoor Visitor, p1.

[4] Abrahams H M. 1959, Britain's National Parks, Country Life Ltd. London, p12.

[5] Abrahams H M. 1959, p10,52,126-130.

[6] Bell M. 1975, Britain's National Parks, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, p28.

[7] Weir J. 1987, Dartmoor National Park, Countryside Commission Guide, Webb & Bower, Devon, p109.

[8] Council For National Parks, 1995, Environment Bill, Briefing for Peers, typescript, January.

[9] HMSO,1985, The Dartmoor Commons Act.

[10] Sage D. 1993, "Who Owns the Moor?" The Dartmoor Visitor, National Park Authority publication, p2.

[11] Blacksell M. Gilg A. 1981, The Countryside: Planning and Change, George, Allen and Unwin, London, p211-213.

[12] Landscape Research Group, 1988, A Review of Recent Practice and Research in Landscape Assessment, Countryside Commission, CCD 25.

[13] Silsoe College, 1991,Landscape Change in National Parks, Countryside Commission, CCP 359.

[14] Tiplady P, 1993, Personal Communication with SDCB Officers.

[15] Landscape Design Associates, 1994, ALandscape Assessment of the Sussex Downs AONB, consultation draft, Oct.

[16] Stamp L D. Briault E W H. & Henderson H C K. 1942, The Land of Britain, Sussex (East and West), Parts 83/84, Geographical Publications Ltd, London.

[17] Kennedy M. 1992, "Things that go Baa in the Night", Guardian, 7 Dec.

[18] Friends of National Parks, 1993, "Dartmoor Initiative", National Parks Today, ed. 35, Spring.

[19] Dartmoor National Park Authority, 1991, Dartmoor National Park Visitor Survey.

[20] Hart C. 1993, Letter to the Author, Devon County Council, 8 Feb.

[21] Grey J. 1995, "Visitor Survey Summary",correspondence with author, Sussex Downs Conservation Board, 6 Feb.

[22] Short B. 1994, personal communication.

[23] Countryside Commission, 1993, The Dartmoor Initiative, Countryside, No6.