Recognition of the Earliest English Renaissance Grotto,

Dr Bruce E Osborne

What and where was the first English Classical Grotto? The influence for building garden grottos came from Italy as part of the 15/16th century Renaissance movement. Capturing the ethos of the ancient Greeks and Romans, Italian garden designers adopted the grotto as an expression of culture and art inherited from a millennium and a half years previous. The idea of the garden grotto as a mystic cave spread throughout Europe and by the 17th century English estates of the wealthy aristocracy incorporated grottoes in the landscaping of their gardens. Stately homes such as Wilton and Chatsworth were supposedly amongst the first to succumb to this trend. Their grottoes were revered by visitors as each competed to create more elaborate and awe inspiring structures using natural material such as semi-precious stones and rocks, shells, statues and water features. Still going strong in Victorian times in Europe, the grotto continued to be a point of interest for the discerning tourist. But who was the real pioneer of the grotto in England?

Modern day scholarship recognises the endeavours of Henry VIII as a major influence in the introduction of classical themes in his building of Nonsuch Palace in the first half of the 16th century. Based at Ewell in Surrey, Nonsuch was, as the name implies, a royal palace like no other, pioneering the use of the latest Italianate Renaissance themes in the building of a creation unlike any other in England. Modern day scholarship however appears to have overlooked the possibility that Henry was similarly a pioneer of the grotto in England.

. The mystery of the exact nature of the Grove of Diana is debated, as is the possible location. The idea that the Grove of Diana was the pioneering renaissance grotto however has not been considered until now (2014). The Grove of Diana has been recorded by archaeologists and historians as an integral part of the Nonsuch estate. Long lost as a surviving feature (as is the palace itself), the grove was one of a number of garden features including a wilderness, banqueting hall and maze. The development of Nonsuch is considered in detail in EPSOM AND EWELL WELLS - Chapter 2, Nonsuch - a Renaissance Balnea by Dr Bruce E Osborne. (2010) This can be accessed on-line at www,EpsomWells.com

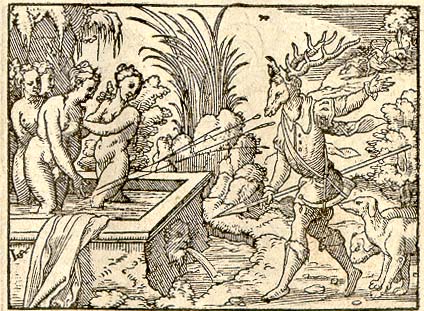

An early description of the Grove of Diana comes from the Rector of Cheam, A Watson c. 1582-92. when Elizabeth I had just come to the throne. Accompanied by flute music, Watson had walked from a woodland menagerie of stone animals to the Grove. He describes a statue of Diana, the mythological goddess of hunting, lurking in the shadows. Here is Actaeon, turned into a stag, shortly before being devoured by his own dogs as retribution for peeping at the bathing goddess. The statue stood on a fountain fed by spring water. Surrounding rocks formed a grotto with flowers in a spray. The garden celebrated Queen Elizabeth with Diana the Virgin Goddess being what some considered was an appropriate metaphor.

Actaeon at the Bath of Diana 1569 - Univ. Glasgow Special Collections

The confirmation that the Grove included what was then a ground breaking grotto and as such the first in England, comes from the Garden and Grove the Italian Renaissance Garden in the English Imagination 1600 - 1750 (1996) John Dixon Hunt. In this is cited the record of German tourist Baron Waldstein's visit to Nonsuch in 1600. Whether the grotto described was completed by Henry VIII or subsequently by the Earl of Arundel after the monarch's death is not apparent. What is clear from the account, reproduced as follows, is that The Grotto of Diana was well established by 1600 and thus one of the earliest if not the first in England.

"Baron Waldstein's visit in 1600 will serve to survey its (Nonsuch Palace) marvels. In the palace he found 'so many miracles of perfected art and of works that rival those of ancient Rome', specifically in the hall 'a collection of sculptures representing stories from Ovid'. Once outside in the 'gardens, the groves', Waldstein found that there were '3 distinct parts [presumably in addition to the Privy Gardens]: the Grove. The Woodland, and the Wilderness'. This variety was further augmented with a great deal of fine statuary and fountains, records of which happily survive in the Lumley Inventory of 1590. (When the gardens were in ruin in the 17th century John Evelyn proposed that the statues should be preserved and displayed after the Italian fashion in a special gallery.) Among the statues Waldstein singles out 'the Labours of Hercules and a number of other subjects from the poets'; but his great enthusiasm is reserved for the Grove of Diana:

By going along the various paths between the growing shrubs, with trees shading us from the summer heat, we entered the famous Grove of Diana, where Nature is imitated with so much skill that you would dare to swear that the original Grove of the real Diana herself was hardly more delightful or of greater beauty. This Grove is approached by a gentle slope leading down from the garden by a path half hidden in the shade of the trees. Before you approach the actual Fountain of Diana you will pass a stone building....

He reads the inscriptions on the wall of this small temple and eventually arrives at the Fountain of Diana itself (the Diana of the Privy Garden had prepared the visitors for the narrative of this woodland grove). The fountain, to judge from other German visitors, seems to have been in the form of a 'grotto or cavern' - surely in the manner of those at Pratolino (i) - in which 'was portrayed with great art and life-like execution the story of how the three goddesses took their bath naked and sprayed Actaeon with water, causing antlers to grow upon his head, and of how his own hounds tore him to pieces'. (ii) The story derives, of course, from Ovid's Metamorphosis, Book III, and despite the lack of hydraulic equipment to start the figures into motion as happened at Pratolino, the visitors all seem to have responded to the groups of statues and their theatrical setting as if they actually saw the scene enacted before their eyes. To underline the narrative, lines of verse were attached to the group, and Waldestein transcribes them in his diary.

Waldestein's account of his visit to England in 1600 leaves no doubt that at the very start of the period with which the book deals Italianate gardening had begun to make its mark."

Sources:

Garden and Grove the Italian Renaissance Garden in the English Imagination 1600 - 1750 (1996) John Dixon Hunt.

Nonsuch: Pearl of the Realm (1992) Lalage Lister, London Borough of Sutton pubs.

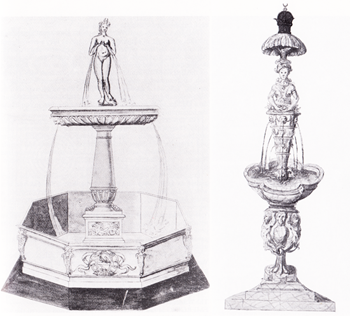

Point requiring further clarification: The exact nature of the Diana fountain is suggested in Lister's book detailed above. Two pictures of fountains are reproduced from the Lumley archives. The first is identified as the Venus Fountain from the Privy Garden, where she has flowing breasts. The second is identified as the Diana Fountain from the Grove where she sits over a spouting urn.

The flowing breasts however are more akin to the Diana of the Villa D'Este as illustrated in Chapter 2. Also other writers identify Diana not Venus in the Privy Garden. Furthermore the Diana Fountain does not replicate the hunter theme associated with the goddess of hunting mentioned by Watson. This throws into question the labelling of these fountains and it may be that confusion has arisen in the past on this point. The two fountains in question are reproduced above.

Footnotes:

i. In 1580 The Villa Medici of Pratolino had a garden with an elaborate network of fountains fed from springs of the nearby mountains - using an intricate system of cisterns and pipes. There were numerous artificial grottoes and moving statues, and mechanical figures activated by water, sometimes accompanied with music (water organs).

ii. The portrayal of Actaeon and the nymphs in the grotto confirms their known presence at Nonsuch and that they were enhancements of the grotto.

Further Reading:

Shell Houses and Grottoes, (2001) Hazel Jackson, Shire.

Heavenly Caves - Reflections on the Garden Grotto (1982) Naomi Miller, George Allen and Unwin.

Dr Bruce E Osborne (2014)

EPSOM AND EWELL WELLS - Addendum to Chapter 2

EPSOM AND EWELL WELLS - Addendum to Chapter 2