|

|

EPSOM AND EWELL WELLS - Chapter 7

EPSOM AND EWELL WELLS - Chapter 7The Zenith of Epsom spa (1712-1750)

Dr Bruce E Osborne

The Zenith of Epsom spa (1712-1750): new treatments, artificial salts, closing the Old Wells, Livingstone's death, amusements, evidence of longevity of spa.

Dr Bruce E Osborne

The Zenith of Epsom spa (1712-1750): new treatments, artificial salts, closing the Old Wells, Livingstone's death, amusements, evidence of longevity of spa.

7.1. Map of Epsom c.1768 as published by John Rocque, at the end of the spa era showing the Old Wells isolated on the common.

The years 1712 to 1750 were the zenith followed by the proverbial sunset, when prosperity was followed by Epsom's demise as a spa. Livingstone's death in 1727 was a turning point for Epsom and it could be argued that this was partially attributable to the reliance that Epsom placed on the New Wells as the principal spa facility.

The town had all the entertainment diversions of a typical spa of the day. John Macky, in 1714, observed that "Gentlemen and Ladies insensibly to lose their company in the pretty labyrinths of Box-wood and divert themselves unperceived....and it may justly be called The Palace of Venus".[1] The Box Wood (Box Hill near Dorking) was considered to be the best in the Kingdom during the 18th century.[2] John Macky also noted that the Old Wells were neglected but still in use.[3] This suggests that the Old Wells were either intermittently closed or just run down and possibly unsupervised. The following year, 1715, John Livingstone having secured the lease on the Old Well eventually locked them, probably to avoid undesirable comparisons and competition with his New Wells.

As recorded by Exwood, this closing of the Old Wells also coincided with a German visitor being advised that not one dram of salt was produced from Epsom Wells.[4] This suggests that either all the Epsom mineralised water was required for local use and could not be made available for the manufacture of artificial salts, or that manufacturing elsewhere had stolen the market. This observation gives a valuable insight as to why manufactured salts were considered a cheat. They did not have a genuine Epsom provenance. Without doubt there was ample supply being made artificially elsewhere by this time, perhaps by Grew at his new factory at Acton or more likely by the Moults using source water from Shooters Hill or from sea water.

Dudley Ryder, an aspiring practitioner of law, later to be Attorney-General, portrays Epsom town in a good light when visiting in 1715. In his diary he recorded on June 13 that he had been extremely sick during the night as a result of a meat pie eaten for supper. At 4 am he arose to go to Epsom via his brothers. On arriving, he left the horses at the Inn at Epsom between 9 and 10 am. After breakfast he looked around the town, visiting the bowling green and the long room, observing that some visitors spent all day at the dice tables. They so little valued the heap of guineas that he was tempted to enter the play, feeling confident that their lack of concern over losing would be to his advantage. In the afternoon he saw plays and music at the bowling green. Whilst at Epsom, Dudley Ryder dined with Lady Harrison and her four daughters. The daughter Celia he found particularly agreeable. Lady Harrison was Celia Fiennes' sister Mary. Ryder returned to London later, fearing a possible attempted robbery on the way.[5]

In the year 1720, a margin note on Ogilby's map of Epsom indicated that Livingstone managed the weekly Friday market in Epsom together with two annual fairs.[6] These were leased from the manor, as secured in 1684 by Lady Evelyn. The margin note on Ogilby's map is suggestive of early advertising.[7] Epsom was well established as a tourist venue of the day as is implied by Prince George of Denmark who frequented Epsom as the consort of Queen Anne, while she held her court at Windsor.[8]

7.2. The New Tavern and Assembly Rooms, later Waterloo House in the High Street was erected in 1692.[9] Facilities included the New Tavern itself, coffeehouse, longroom, cockpit, stables, storehouse and brew house together with ground of about two acres including a bowling green.[10]

About this time Daniel Defoe published anonymously his account of Epsom but the dating is unreliable. Defoe recorded Epsom in his letter 2, published in 1724. The dating of Defoe's work is the subject of intense speculation, much of his data being an amalgam of personal experience and other authors' work. For example, he or a namesake was a witness to the will of Celia Fiennes and it is not impossible that he was familiar with her journals, although Rogers disputes any connection.[11] The date of 1722 for Defoe's description is taken from Rogers but Clark suggests a date of 1717 or earlier, perhaps coinciding with Celia Fiennes' second visit and Toland's earlier description.[12]

Various textual evidence within Defoe's work gives clues to the provenance. Clark noted that Defoe discussed Durdans, the fine park of the late Lord Berkeley. The point that Clark made relates to Defoe commenting on the closing of the Park for walking "for a known reason" otherwise unstated. This was likely because of the intrigue between Lord Grey of Wark and Lady Henrietta Berkeley, which led to a state trial in 1684. Aubrey's text mentioned this amorous affair, citing the Grove at Durdans as the venue for the adventures.[13] Both Aubrey and Defoe referred to "shipwrecked" female disposition and it is likely that Defoe relied on Aubrey or a common source for information and phrasing. Unlike Aubrey, the Defoe account was oblique and did not name Lord Grey or his Lady's sister for reasons that we can speculate on, but are likely linked with Defoe's sensitive political positioning and his abortive trial in the King's Bench in 1715.[14] Defoe had worded his account to accommodate Lord Berkeley's death in 1698 and then used the vague phrase "some years before" to record the reinstatement of walking in the park. Defoe thus updated the earlier information, for publication anonymously in 1724. Reference to the South Sea Bubble and information from conversations with Londoners visiting Epsom further rendered the account current.[15] Defoe noted that the trees around the town were well grown. Parkhurst planted the trees c.1702-9 suggesting up to date knowledge in 1724. What is apparent is that Defoe used data from a variety of sources and dates gathered over time and sought to update specific key points as he went to press.

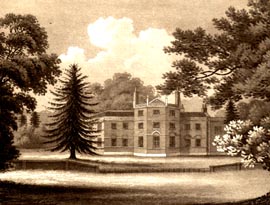

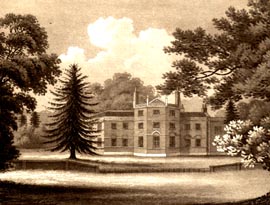

7.3. Durdans circa 1825 from Pownall.

7.3. Durdans circa 1825 from Pownall.

Defoe saw Epsom as a place of pleasure. For a shilling or half a crown one could became a citizen of Epsom for the summer and then drink the waters. Many had the waters brought to their apartments in the morning. Otherwise the day was spent in leisure, available to suit all tastes. The bowling green became the centre of activity in the evening; only one green was mentioned. The character of ladies was often devastated at Epsom, unlike Tunbridge, such havoc being caused through "tattle and slander" . For those seeking a country debauch, Box Hill was a popular excursion venue. Many visitors were business people from London and commuting was a regular practice. The gentry went to Tunbridge, the merchants to Epsom. Defoe saw Epsom as a summer retreat and found it no place for pleasure in the winter.[16] The impression that Defoe's work gives is of a competent updated account of the town as it was in the early eighteenth century. A number of points suggest that current social and political points are accommodated to make it relevant to the 1720s but it is in the echoes of the past that we are able to identify earlier scripts. Importantly he made no criticism of the waters. However, Defoe's second edition of 1738 discusses the spa in the past tense rather than current, which indicates the demise and its approximate date.[17] Defoe did suggest that Epsom and its environs were the place to debauch, a theme that was to recur continually. It was noted in 1722 that common (loose) women were less likely to be met with at Bath than at Epsom. The suggestion was that this may be attributable to the relatively easily covered distance from London.[18]

Whilst the 1720s were a period of lively prosperity, the people of Epsom had little idea of what would follow Livingstone's death in the year 1727. For example the Old Wells had remained closed until his death. The Old Well was then revived and the rooms improved by Parkhurst the younger, as lord of the manor.[19] Livingstone's estate was left divided between his two daughters.[20] During his lifetime he had given land for almshouses for 12 poor widows in East Street. These were the "Cane's Charity, Livingstone's Almshouses".[21] Livingstone's death appears to have heralded the demise of Epsom as a tourist spa town. The fashionables were no doubt setting their sights elsewhere for reasons to be debated.

Evidence indicates that the spa continued for some years after Livingstone's death although Defoe wrote historically about the spa in 1738. The social emphasis appears to change and taking the waters was only one of the attractions. Horse racing and sexual liaisons were overtaking the more traditional appeal. Salmon wrote in 1728 that the mineral waters of Ebesham (Epsom) had resulted in the town being visited by tourists as well as becoming a retirement locality. He noted a new course on the Downs nearer to the wells than the one near Carshalton.[22] This is a reference to the new racing circuit superseding the "straight" to Banstead Downs. The Abbe Prevost, in 1734, recorded that of all the places in the world, those in which pleasures were most lavishly multiplied and continue with least interruption included Epsom. It was also noted that young men visited Epsom to take a course, as it were, in profligacy. Having trained at the regular watering places, Bath became the final stage of the apprenticeship before London.[23]

7.4. Sally Mapp the bonesetter by Hogarth. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

In 1736, Mrs Mapp, the notorious "female bone setter" plied her calling at Epsom and gave a fillip to the taking of the waters.[24] Sally Wallin, also known as "Crazy Sally" enjoyed great repute in setting broken bones and joints. She was the daughter of a bone setter as well as being a bone setter herself. Her sister enjoyed repute in the theatre until marrying the Duke of Bolton.[25] Sally, when seeking to leave to marry a Mr Mapp found the inhabitants of Epsom trying to prevent her departure. The London Magazine considered that she received near 20 guineas a day for expediently setting limbs. Epsom local authorities offered her 100 guineas to remain in the town for one year.[26] On one occasion an impostor was sent to her for treatment, by surgeons who envied her abilities. She quickly broke the impostor's limbs, redirecting him to those who sent him.[27]

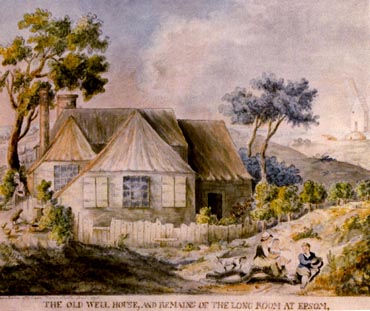

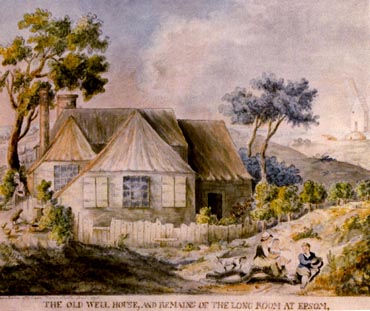

In spite of Sally Mapp, by 1738 the buildings and facilities at the Old Wells had decayed leaving a single dwelling occupied by a countryman and his wife who carried water around the neighbourhood in bottles.[28] Addison attributed this comment to The Ambulator of 1782, detailed later. The dwelling is the cottage illustrated in 1796 and described as "The Old Well House and Remains of the Long Room at Epsom, Surrey". The building is identified as the surviving corner of the Assembly Rooms and can be seen in the distance on Pownall's 1825 picture - see below.[29]

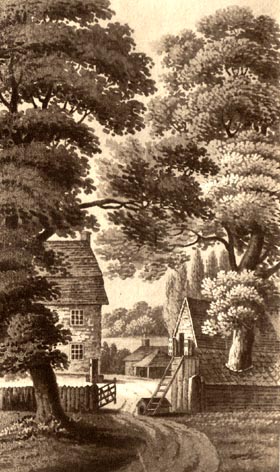

7.5. Pownall's 1825 picture of Epsom Old Wells showing the pump and beyond, to the right, the building containing the long light (Assembly) room that Celia Fiennes observed.

7.5. Pownall's 1825 picture of Epsom Old Wells showing the pump and beyond, to the right, the building containing the long light (Assembly) room that Celia Fiennes observed.

In the early 1750s, probably 1751, Dr John Burton made a perambulation of Surrey and Sussex that he recorded for posterity. "Lower down, on the edge of the plain, we saw Epsom, a well-built and populous village, formerly highly celebrated for its medicinal springs, which are said to be both astringent and purgative. Perhaps they are both; at any rate, the leading physicians here prescribe them as both. But now the medical fame has waned, and those who sojourn here are not invalid water-drinkers, but valiant wine-bibbers and gamblers, followers of all sorts of sport and pleasure." Here we have confirmation that Epsom as a spa is finished. Instead tourism is based on less reputable pursuits. Malden (1916), who translated Dr Burton's account from the original Greek and Latin, adds an interesting footnote, which can now be evaluated in an enlightened manner. "The Medicinal Well at Epsom was closed in 1706 to 1727 by a Dr. Levingstone [sic], who obtained a lease on it, and who opened a harmless well and Assembly Rooms of his own nearer the town. Though the well was reopened, Epsom never regained its medicinal fame. It continued as described by Dr. Burton; but Epsom salts could be made elsewhere." Apart from the error in the dates, such interpretation of Epsom's demise will be shown to need substantial revision.[30]

7.6. The Assembly Rooms at the Old Wells later used as a cottage. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

7.6. The Assembly Rooms at the Old Wells later used as a cottage. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

Further evidence of the demise of Epsom however comes in 1745. Barbeau recorded the comments of the Abbe Le Blanc whilst returning from Bath in 1745 who considered that Epsom, Tunbridge and Scarborough were out of fashion. If one went to drink the waters without being ill, one should at least choose those where one was sure to find the best company.[31]

By the mid 18th century Epsom was rapidly becoming a fashionable residential and retirement town. The spa was extinct and new residences such as Pitt House had their own hot and cold bathing facilities.[32] Inevitably the people of Epsom were to bemoan the changes that were taking place, especially the loss of the spa whilst other resorts elsewhere enjoyed expanding prosperity. What the public wanted was a scapegoat as is so often the case when events go adversely. In the next chapter the scapegoat is discussed.

Click on website below to return to Index and Introduction.

The years 1712 to 1750 were the zenith followed by the proverbial sunset, when prosperity was followed by Epsom's demise as a spa. Livingstone's death in 1727 was a turning point for Epsom and it could be argued that this was partially attributable to the reliance that Epsom placed on the New Wells as the principal spa facility.

The town had all the entertainment diversions of a typical spa of the day. John Macky, in 1714, observed that "Gentlemen and Ladies insensibly to lose their company in the pretty labyrinths of Box-wood and divert themselves unperceived....and it may justly be called The Palace of Venus".[1] The Box Wood (Box Hill near Dorking) was considered to be the best in the Kingdom during the 18th century.[2] John Macky also noted that the Old Wells were neglected but still in use.[3] This suggests that the Old Wells were either intermittently closed or just run down and possibly unsupervised. The following year, 1715, John Livingstone having secured the lease on the Old Well eventually locked them, probably to avoid undesirable comparisons and competition with his New Wells.

As recorded by Exwood, this closing of the Old Wells also coincided with a German visitor being advised that not one dram of salt was produced from Epsom Wells.[4] This suggests that either all the Epsom mineralised water was required for local use and could not be made available for the manufacture of artificial salts, or that manufacturing elsewhere had stolen the market. This observation gives a valuable insight as to why manufactured salts were considered a cheat. They did not have a genuine Epsom provenance. Without doubt there was ample supply being made artificially elsewhere by this time, perhaps by Grew at his new factory at Acton or more likely by the Moults using source water from Shooters Hill or from sea water.

Dudley Ryder, an aspiring practitioner of law, later to be Attorney-General, portrays Epsom town in a good light when visiting in 1715. In his diary he recorded on June 13 that he had been extremely sick during the night as a result of a meat pie eaten for supper. At 4 am he arose to go to Epsom via his brothers. On arriving, he left the horses at the Inn at Epsom between 9 and 10 am. After breakfast he looked around the town, visiting the bowling green and the long room, observing that some visitors spent all day at the dice tables. They so little valued the heap of guineas that he was tempted to enter the play, feeling confident that their lack of concern over losing would be to his advantage. In the afternoon he saw plays and music at the bowling green. Whilst at Epsom, Dudley Ryder dined with Lady Harrison and her four daughters. The daughter Celia he found particularly agreeable. Lady Harrison was Celia Fiennes' sister Mary. Ryder returned to London later, fearing a possible attempted robbery on the way.[5]

In the year 1720, a margin note on Ogilby's map of Epsom indicated that Livingstone managed the weekly Friday market in Epsom together with two annual fairs.[6] These were leased from the manor, as secured in 1684 by Lady Evelyn. The margin note on Ogilby's map is suggestive of early advertising.[7] Epsom was well established as a tourist venue of the day as is implied by Prince George of Denmark who frequented Epsom as the consort of Queen Anne, while she held her court at Windsor.[8]

7.2. The New Tavern and Assembly Rooms, later Waterloo House in the High Street was erected in 1692.[9] Facilities included the New Tavern itself, coffeehouse, longroom, cockpit, stables, storehouse and brew house together with ground of about two acres including a bowling green.[10]

About this time Daniel Defoe published anonymously his account of Epsom but the dating is unreliable. Defoe recorded Epsom in his letter 2, published in 1724. The dating of Defoe's work is the subject of intense speculation, much of his data being an amalgam of personal experience and other authors' work. For example, he or a namesake was a witness to the will of Celia Fiennes and it is not impossible that he was familiar with her journals, although Rogers disputes any connection.[11] The date of 1722 for Defoe's description is taken from Rogers but Clark suggests a date of 1717 or earlier, perhaps coinciding with Celia Fiennes' second visit and Toland's earlier description.[12]

Various textual evidence within Defoe's work gives clues to the provenance. Clark noted that Defoe discussed Durdans, the fine park of the late Lord Berkeley. The point that Clark made relates to Defoe commenting on the closing of the Park for walking "for a known reason" otherwise unstated. This was likely because of the intrigue between Lord Grey of Wark and Lady Henrietta Berkeley, which led to a state trial in 1684. Aubrey's text mentioned this amorous affair, citing the Grove at Durdans as the venue for the adventures.[13] Both Aubrey and Defoe referred to "shipwrecked" female disposition and it is likely that Defoe relied on Aubrey or a common source for information and phrasing. Unlike Aubrey, the Defoe account was oblique and did not name Lord Grey or his Lady's sister for reasons that we can speculate on, but are likely linked with Defoe's sensitive political positioning and his abortive trial in the King's Bench in 1715.[14] Defoe had worded his account to accommodate Lord Berkeley's death in 1698 and then used the vague phrase "some years before" to record the reinstatement of walking in the park. Defoe thus updated the earlier information, for publication anonymously in 1724. Reference to the South Sea Bubble and information from conversations with Londoners visiting Epsom further rendered the account current.[15] Defoe noted that the trees around the town were well grown. Parkhurst planted the trees c.1702-9 suggesting up to date knowledge in 1724. What is apparent is that Defoe used data from a variety of sources and dates gathered over time and sought to update specific key points as he went to press.

7.3. Durdans circa 1825 from Pownall.

7.3. Durdans circa 1825 from Pownall. Defoe saw Epsom as a place of pleasure. For a shilling or half a crown one could became a citizen of Epsom for the summer and then drink the waters. Many had the waters brought to their apartments in the morning. Otherwise the day was spent in leisure, available to suit all tastes. The bowling green became the centre of activity in the evening; only one green was mentioned. The character of ladies was often devastated at Epsom, unlike Tunbridge, such havoc being caused through "tattle and slander" . For those seeking a country debauch, Box Hill was a popular excursion venue. Many visitors were business people from London and commuting was a regular practice. The gentry went to Tunbridge, the merchants to Epsom. Defoe saw Epsom as a summer retreat and found it no place for pleasure in the winter.[16] The impression that Defoe's work gives is of a competent updated account of the town as it was in the early eighteenth century. A number of points suggest that current social and political points are accommodated to make it relevant to the 1720s but it is in the echoes of the past that we are able to identify earlier scripts. Importantly he made no criticism of the waters. However, Defoe's second edition of 1738 discusses the spa in the past tense rather than current, which indicates the demise and its approximate date.[17] Defoe did suggest that Epsom and its environs were the place to debauch, a theme that was to recur continually. It was noted in 1722 that common (loose) women were less likely to be met with at Bath than at Epsom. The suggestion was that this may be attributable to the relatively easily covered distance from London.[18]

Whilst the 1720s were a period of lively prosperity, the people of Epsom had little idea of what would follow Livingstone's death in the year 1727. For example the Old Wells had remained closed until his death. The Old Well was then revived and the rooms improved by Parkhurst the younger, as lord of the manor.[19] Livingstone's estate was left divided between his two daughters.[20] During his lifetime he had given land for almshouses for 12 poor widows in East Street. These were the "Cane's Charity, Livingstone's Almshouses".[21] Livingstone's death appears to have heralded the demise of Epsom as a tourist spa town. The fashionables were no doubt setting their sights elsewhere for reasons to be debated.

Evidence indicates that the spa continued for some years after Livingstone's death although Defoe wrote historically about the spa in 1738. The social emphasis appears to change and taking the waters was only one of the attractions. Horse racing and sexual liaisons were overtaking the more traditional appeal. Salmon wrote in 1728 that the mineral waters of Ebesham (Epsom) had resulted in the town being visited by tourists as well as becoming a retirement locality. He noted a new course on the Downs nearer to the wells than the one near Carshalton.[22] This is a reference to the new racing circuit superseding the "straight" to Banstead Downs. The Abbe Prevost, in 1734, recorded that of all the places in the world, those in which pleasures were most lavishly multiplied and continue with least interruption included Epsom. It was also noted that young men visited Epsom to take a course, as it were, in profligacy. Having trained at the regular watering places, Bath became the final stage of the apprenticeship before London.[23]

7.4. Sally Mapp the bonesetter by Hogarth. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

In 1736, Mrs Mapp, the notorious "female bone setter" plied her calling at Epsom and gave a fillip to the taking of the waters.[24] Sally Wallin, also known as "Crazy Sally" enjoyed great repute in setting broken bones and joints. She was the daughter of a bone setter as well as being a bone setter herself. Her sister enjoyed repute in the theatre until marrying the Duke of Bolton.[25] Sally, when seeking to leave to marry a Mr Mapp found the inhabitants of Epsom trying to prevent her departure. The London Magazine considered that she received near 20 guineas a day for expediently setting limbs. Epsom local authorities offered her 100 guineas to remain in the town for one year.[26] On one occasion an impostor was sent to her for treatment, by surgeons who envied her abilities. She quickly broke the impostor's limbs, redirecting him to those who sent him.[27]

In spite of Sally Mapp, by 1738 the buildings and facilities at the Old Wells had decayed leaving a single dwelling occupied by a countryman and his wife who carried water around the neighbourhood in bottles.[28] Addison attributed this comment to The Ambulator of 1782, detailed later. The dwelling is the cottage illustrated in 1796 and described as "The Old Well House and Remains of the Long Room at Epsom, Surrey". The building is identified as the surviving corner of the Assembly Rooms and can be seen in the distance on Pownall's 1825 picture - see below.[29]

7.5. Pownall's 1825 picture of Epsom Old Wells showing the pump and beyond, to the right, the building containing the long light (Assembly) room that Celia Fiennes observed.

7.5. Pownall's 1825 picture of Epsom Old Wells showing the pump and beyond, to the right, the building containing the long light (Assembly) room that Celia Fiennes observed. In the early 1750s, probably 1751, Dr John Burton made a perambulation of Surrey and Sussex that he recorded for posterity. "Lower down, on the edge of the plain, we saw Epsom, a well-built and populous village, formerly highly celebrated for its medicinal springs, which are said to be both astringent and purgative. Perhaps they are both; at any rate, the leading physicians here prescribe them as both. But now the medical fame has waned, and those who sojourn here are not invalid water-drinkers, but valiant wine-bibbers and gamblers, followers of all sorts of sport and pleasure." Here we have confirmation that Epsom as a spa is finished. Instead tourism is based on less reputable pursuits. Malden (1916), who translated Dr Burton's account from the original Greek and Latin, adds an interesting footnote, which can now be evaluated in an enlightened manner. "The Medicinal Well at Epsom was closed in 1706 to 1727 by a Dr. Levingstone [sic], who obtained a lease on it, and who opened a harmless well and Assembly Rooms of his own nearer the town. Though the well was reopened, Epsom never regained its medicinal fame. It continued as described by Dr. Burton; but Epsom salts could be made elsewhere." Apart from the error in the dates, such interpretation of Epsom's demise will be shown to need substantial revision.[30]

7.6. The Assembly Rooms at the Old Wells later used as a cottage. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum)

7.6. The Assembly Rooms at the Old Wells later used as a cottage. (courtesy Bourne Hall Museum) Further evidence of the demise of Epsom however comes in 1745. Barbeau recorded the comments of the Abbe Le Blanc whilst returning from Bath in 1745 who considered that Epsom, Tunbridge and Scarborough were out of fashion. If one went to drink the waters without being ill, one should at least choose those where one was sure to find the best company.[31]

By the mid 18th century Epsom was rapidly becoming a fashionable residential and retirement town. The spa was extinct and new residences such as Pitt House had their own hot and cold bathing facilities.[32] Inevitably the people of Epsom were to bemoan the changes that were taking place, especially the loss of the spa whilst other resorts elsewhere enjoyed expanding prosperity. What the public wanted was a scapegoat as is so often the case when events go adversely. In the next chapter the scapegoat is discussed.

Click on website below to return to Index and Introduction.

Website: Click Here

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

1) TOPOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

England

3) INFORMATION CATEGORY:

Springs and Wells General InterestHistory & Heritage