|

|

EPSOM AND EWELL WELLS - Chapter 4

EPSOM AND EWELL WELLS - Chapter 4Flourishing spa (1660-1690)

Dr Bruce E Osborne

Developments, visitors, reputation, demise of Nonsuch, Appendix: News from Epsom.

The 1660s saw Epsom embarking on a period of prosperity as a significant health resort combining the pursuit of health with the pursuit of leisure. There are hints of stagnation as the 1690s approached, soon to be rectified with the onset of the new century.

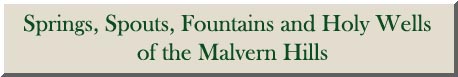

4:1 Schellinks drawing of Epsom Well, 1662./ Samuel Pepys.

In 1662 we have the earliest known illustration of Epsom Wells. The detail includes a small building located on an otherwise undeveloped common with scrub interspersed by people congregating around the well. In the bushes are those whose imbibing of the waters was giving rise to the renowned purging effect. What is apparent is that the facilities were severely limited. William Schellinks, the artist who drew this early picture of Epsom Well, described the location in his travel journal.[1] He was one of three artists commissioned by Laurence van de Hem, son of a prosperous Dutch merchant, to record the scenery of Europe.

Schellinks visited the well on four separate days. In the account which follows, the present author's comments are in square [ ] brackets.

"On the 5 June [1662] at 9 o'clock in the morning we walked with Mr Pelt from Kingston to Epsom, being 5 miles. We got there midday, and went to stay at one Robin Bird, and were there well accommodated. Epsom is a very famous and very pleasant place, much visited because of the water, which lies in a valley not far from there, which is much drunk for health reasons, because of its purgative powers, and which is being sent in stoneware jars throughout the land. [these would likely be similar to the German "Kruke, irdener Krug", made of clay and often impressed with the provenance of the contents, to date no recorded example has been identified from Epsom although the Science Museum has one from Godstone in Surrey for Iron Pear Tree Water, circa 1750/60 [2]] It is a well, and with a wall around raised as a well head, and there is ground paved with bricks. In the middle it has an opening in the ground for the water flow, and the well water, reckoned from there, stands ten spans high and eight spans from the brick floor. [a span is generally reckoned to be 9 inches, this makes the depth of water from the floor 6 feet and the height of the wall surrounding the well 18 inches] This well stands at the back in a small house, in which there are some small rooms, and many people come in there to drink and to shelter from the sun. For this well a yearly rent of twelve pound sterling is paid, which is given to the poor. Those who come to drink the water give to the person who draws it as much as they wish. Now in 1662 an old man and woman have it on hire. [this point is confirmed by Samuel Pepys in 1667]

The practice of drinking the water is from early in the morning until 8, 9, or 10 o'clock. It is drunk on an empty stomach from stoneware mugs holding about one pint. Some drink ten, twelve, even fifteen or sixteen pints in one journey, but everyone as much as he can take. And one must then go for a walk; it works extraordinary well, with various funny results - probatum est. Gentlemen and ladies have here separate meeting places, putting down sentinels in the shrub in every direction. It has happened that the well was drunk empty three times in one morning; in hot and dry summers, when the water does not get any feed from above, but has to work up from the lower parts of the ground, it has more strength, and the people who observe this come then in such crowds that the village which is fairly large and can spread at least 300 beds, is still too small, and the people are forced to look for lodgings in the neighbourhood. [Pepys went to Ashtead the following year] Some stay there on doctor's orders for several weeks continuously into the middle of the summer, drinking daily from this water, and many people take some hot meal broth or ale after drinking the water. I have added hereto my drawing of the described place." [see front illustration]

Schellinks goes on to recount an experience that night. A disturbance in the house was thought to be thieves and the alarm was raised. It transpired that it was a wayward pig that had strayed into the kitchen only to be redirected by the maid. The travelling companions spent the rest of the night in the same bed for security.

"On the 6 June in the morning we went to the water well, and each drank three or four pints of water, as much as the day before, and went for a walk, and at 11 o'clock we returned to Kingston, where we arrived at 2 o'clock....

....to Kingston, and at 5 o'clock I went on foot with Mr Thierry once more to Epsom; on the way we bought a fat goose for 16 pence and had it roasted at our lodgings, where we stayed again, which was not at all bad.

The 11th June at 7 o'clock in the morning we went again to the well and found there again much company, on foot and on horseback, gentlemen, ladies, men and girls, Dutch, French, etc. [this confirms an international tourist trade] We drank six large pints of the water and then went for a walk, but the whole result was but one stool. To follow the fashion we went to our lodging to take there some bread and meat broth. In the afternoon we went to explore the countryside all around, which was very pleasant.

On the 12 June in the morning we went again to the well and found again a lot of people. After having broken our fast with the water we went to wash it down with a cup of warm ale and so went from Epsom to the wonderful place of Lord Berkeley, which is extraordinary pleasant, the house as well as the garden. [Durdans which features extensively in the early history of Epsom] The place has a very excellent avenue with many large trees, and a very beautiful gatehouse. Amongst other rooms we saw a very beautiful one full of paintings, and others richly furnished, also a fine chapel and a large hall etc. The garden is very pleasant because of natural hills and dales, adorned with fountains, sculptures, cypress trees, a maze, wildernesses, grottoes, bowers, avenues or walks, summerhouses, a bowling green etc., all in Italian style." [3]

Durdans was a substantial house at this time and of considerable local importance. In the 1650s it was the home of Sir Robert Coke, Lord Chief Justice who had married a Berkeley. George, the ninth Earl Berkeley inherited the house in 1652 and it became a mecca for high society. It was rebuilt using the materials from Nonsuch Palace shortly after Schellinks visit in 1662, only to be burnt down and again rebuilt in time for Celia Fiennes in the 1690s. Little record remains of this earlier house, it was the later one that was seen by Celia Fiennes and recorded in her first account of Epsom.[4] Epsom was a town of some prestige by this time. In 1662 George, Earl Berkeley, entertained Charles II at Epsom with his brother and Samuel Pepys.[5] John Evelyn the diarist, met the King and Queen, the Duke and Duchess of York, Prince Rupert and various noblemen on this occasion.[6] Charles II incidentally came again to Epsom in 1664.

The Berkeleys were the keepers of Nonsuch Palace endorsing the constant associations between Epsom and Nonsuch. From Schellinks' description of Durdans, it is worthy of note that the Renaissance Italian influence, which was so important in the conceptualisation of Nonsuch Palace, was also adopted at Durdans; perhaps the creators of Durdans sought to replicate the ambience of the celebration of mythology and water noted at Nonsuch.

The arrival of Samuel Pepys on July 25th 1663 was not without problems. Pepys noted that the town was full and had to lodge in Ashtead, an experience that came in for some criticism due to the quality of the accommodation. Visiting Ashtead gave him an opportunity to visit his cousin whose house was not as grand as he recalled as a child. Ashtead was only one mile from the Old Wells, about two from Epsom town. Pepys noted the surprising number of people in Epsom, including some people of quality, with little else to do but drink the water. Epsom town centre facilities, like those at the wells, were clearly limited at this time.[7]

The year 1663 saw the ballad Merry Newes from Epsom Wells launched which gave interesting insights into social life at Epsom.[8] The plot is about a lawyer who has a fling with a goldsmiths wife, while the lawyers wife is collecting the Epsom water. A calamity ensues and the lawyer, after making a speech leaves town. The drinking of Epsom Water appears synonymous with licentious behaviour. The following is an extract from the full text.

4.2 When the back is turned, early cartoon.

"The lawyers wife, with famous hands

the chamber door doth make fast.

It grieved her sore to face the whore

had got away her breakfast.

She opes the casement, and she calls

all people to the slaughter.

How most unluckily it falls

his wife should watch his water.

To save his life he takes his wife

and out of town he trudges

the lawyers fact, is censured by

almost a thousand judges.

They flout and sneer, they jest and jear

the town is full of laughter

But many of them that were there

had paddled in such water.

Away he goes, filled full of woes

to think what will come after

He that loves life, let him keep his wife

from drinking Epsom Water."

Also in year 1663, Richard Evelyn, brother of the diarist, became lord of the manor.[9] Also about this time, according to the Epsom Commons Association, a roughly circular area around the Old Well was cleared and rights of common were curtailed. This encroachment of the manorial commons enabled the crowds to be accommodated, and being a purging well, meant that the area surrounding the spring was not contaminated by the inevitable pollution. The area was 40 rods in radius, about 450 yards in diameter and can be identified on nineteenth century maps. The earliest map showing this is the 1866 25 inch OS map.[10] It does not appear on the first edition OS map of 1810-17. This enclosure was later to determine the incongruous area of mid-twentieth century urban housing now surrounding The Wells. The avoidance of one pollution subsequently precipitated another!

The fact that Epsom provided an easily accessible resort from London is apparent in 1665 when Richard Evelyn, JP. and lord of the manor, was obliged to close the wells due to possible spread of infection from the Great Plague.[11] The instruction, issued by the Surrey Quarter Sessions, directed that the wells be locked and no person permitted to drink the waters. This may also have been the consideration behind the clearing of the circular area around the well mentioned in the previous paragraph. The legal instruction noted that there had been a substantial influx of visitors to the town from London on the pretext of drinking the waters, no doubt to escape the ravishes of the plague.[12] By modern day standards Epsom was a small settlement in spite of its visitor numbers and it is difficult to appreciate the intimacy that must have existed compared with the impersonal indifference that features in modern day urban society.

By 1667 Samuel Pepys was back in Epsom. He left London at five in the morning to journey to the wells to drink the mineral water at the appropriate time, as well as to fill containers to take home. At the well he learnt from the woman attendant that the well was rented from the lord of the manor for £12 a year, thereby confirming the earlier information recorded by Schellinks.[13] Pepys wrote in his diary in July, "To Epsum by eight o'clock, to the well; where much company, and I drank the water: they did not, but I did drink four pints. And to the towne to the King's Head; and hear my Lord Buckurst and Nelly (Nell Gwynne) are lodged at the next house, and Sir Charles Sedley with them: and keep a merry house."[14]

4.3 Charles II with Nell Gwyn. Melville 1923.

4.3 Charles II with Nell Gwyn. Melville 1923.

Lewis Melville (1923) provides interesting background to this amorous rendezvous. Nell Gwyn was without doubt a woman with qualities that attracted men, apart from a reputation of running up huge bills on account. Charles Sackville, Lord Buckhurst, afterwards sixth Earl of Dorset and first Earl of Middlesex was for a while the acknowledged lover of Ms.Gwyn. On May Day in 1667 Pepys had seen Nell in her lodgings in Drury Lane, London. Buckhurst about this time started his amorous adventure with the lady, taking her to Epsom to remove her from the theatrical circles within which she circulated. Pepys expressed concern that Nell was leaving the theatre where she gave great pleasure to audiences with her charm. By August Nell was back in London at the Kings House where she played Cydaria in "The Indian Emperor”. This appears to have been the closing stages of the Buckhurst love affair and it is interesting to note that Buckhurst was sent to France by the King on a fool’s errand the following Christmas and made Earl of Middlesex. By January 1668 Charles II was liaising with Nell Gwyn and it appears that an amorous affair had been in the offing some weeks previous. This would explain the position of Buckhurst. The King thereafter commandeered Nell’s attentions at the expense of Lady Castlemaine who he "compensated” in 1670 by making her Baroness Nonsuch, Countess of Southampton and Duchess of Cleveland, and at the same time giving her Nonsuch Palace. The King’s affair with Nell was to have longevity, when he died in 1685 she sincerely mourned his demise.[15]

As Samuel Pepys no doubt found out, drinking 4 pints of mineralised water was a daunting prospect. In the Bohemian spas a custom arose of eating a wafer while taking the waters. This custom remains to this day and the "Kolonada Luxus" continues to be produced locally. Bath became noted for its Bath Oliver biscuits as a result of the efforts of Dr Oliver to make the waters more palatable. Such a practice likely took place in Epsom in order to render the waters more palatable. A wafer iron in the Guildford Museum lends credence to this belief.

In the same year as Pepys' later visit, 1667, two convictions for running a disorderly house and another for keeping an unlicensed common tippling house were recorded.[16] Things were without doubt lively in Epsom but it was not only at the spa that one could be relieved of ones money. A popular misconception is that it was customary for travellers between London and Epsom to be waylaid. The people of Tooting had a reputation for what became almost extortion in an effort to foist their goods and services on the trippers. Such a practice gave rise to the expression "tooting" or "touting".[17] The truth is that to tout was first recorded about 1700 and was to peer at or look out for, this particularly applied to watching a horse for betting purposes. The maligned people of Tooting were in fact named after the ancient peoples of "tota”. Although this plausible legend is false, it is suggestive of the character of the times and the practice of touting has application in many modern tourism resorts as well as likely taking place on the roads to Epsom. Touting and Tooting were perhaps just an unfortunate coincidence of vocabulary.

As the seventeenth century progressed, the year of 1668 saw a number of minor occurrences that give an insight into the activities at the spa. Many doctors advised a visit to Epsom, and the Court of Charles II and other fashionable people visited the town.[18] In Pepys' domestic papers are letters from John Owen requesting 12 days leave to visit the Epsom Wells in June followed by a further request in August.[19] The Court Rolls record that the wall erected by Richard Evelyn around a well near the main Well had been broken down and this was prejudicial to those taking the waters. This suggests more than one well and that the one mentioned was under the control of the manor.[20]

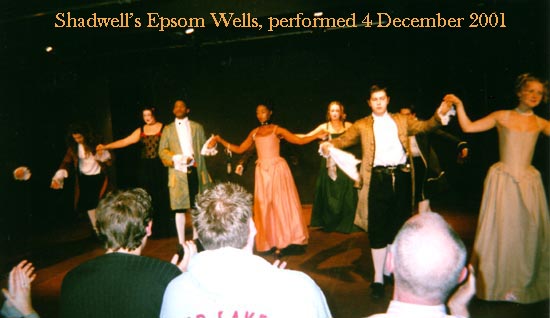

In 1670, Nonsuch Palace was given by Charles II to Barbara Villiers, who rapidly demolished it. The ruins of Nonsuch were subsequently used to construct the buildings in the town. Thereafter there was no royal palace in the locality of Epsom.[21] Shadwell's comedy, Epsom Wells, began a long run at the Duke's Theatre in 1673, having been written the year before. Epsom was portrayed as a place of licentious behaviour and scandalous goings on.[22] This suggests that Epsom society had moved "downmarket" perhaps following the demise of Nonsuch Palace and abandonment by the aristocracy. Brighton followed a similar sequence in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Initially it attracted the aristocracy of the Regency period and the Royal Pavilion was built. Later Royalty went elsewhere and the town became a centre for entertainment and pleasure, much of it of a dubious nature.[23]

4.4 Shadwell's 17th century Epsom Wells, performed in 2001 by the Ralph Richardson Memorial Studios, Wood Green, directed by John Tarlton.

Another unfortunate event in 1670 was the demise of Richard Evelyn, lord of the manor, who died early in March from calculus, a concretion found in the body. John Evelyn, the diarist, records that his brother's body was opened and a stone not much bigger than a nutmeg was removed from his bladder. In addition his liver and kidneys were faulty, accounting for the intolerable pain that Richard experienced before death. The suggestion is that he died of over consumption of Epsom Waters, having drunk them when in good health, thereby no doubt reducing Lady Elizabeth Evelyn's enthusiasm for the waters.[24] John Evelyn came to Epsom for the funeral.[25] Following her husband's death, Lady Evelyn took over the manorial responsibilities. Elizabeth Evelyn, as lady of the manor, held courts from 1670 to 1691.[26] In the same year, 1670, as a result of a dispute with tenants, she caused the spring to be stopped up, but a new well was discovered at Slyfield, 4 to 5 miles away in Stoke D'Abernon, in 1671. Soon after, the original well at "Ebsham" was reopened with houses to accommodate the reception of strangers.[27] In 1675 the Court Baron recorded that a building solely for the purpose of taking the waters was to be erected on the common annexed to the public wells.[28]

The provision of games and entertainment facilities was important to any developing spa resort at the time. Bowling was popular on outdoor greens and Epsom made provision for the game. William Head of the Kings Head purchased an acre of land adjacent to the bowling green in 1671. This indicates that the lower bowling green, later noted by Celia Fiennes, was in existence by this date. In 1678, William Glover, the bowling green owner, had died leaving a bowling alley on 2 acres known as Phillips Close. It abutted the Kings Head on the east and the High Street on the north and west. It was therefore on the south side of the present High Street opposite the Clock Tower. The green proved successful and attracted substantial custom from the 1680s.[29] A survey of 1688 reveals a further bowling green at Epsom. George Richbell, a yeoman, owned a meadow close to a bowling green. The location was near Summersgate Lane, now Wheeler's Lane, and Clay Hill now West Hill. It was not particularly successful and is not mentioned by contemporary writers. Last record of it was in 1727 when it was described as a former bowling green.[30] The second green was taken over in 1688 by Ashenhurst, who also had an interest in the other. Having secured a monopoly, he closed the second green.[31]

Indications are that an infrastructure to accommodate and entertain visitors was being developed by the 1670s in Epsom. The New Inn was mentioned in the Court Baron of 1672. Another of similar name subsequently became the White Horse in Dorking Road and not to be confused with the later Waterloo House in the High Street. Waterloo House was known as the New Tavern and likely had a longroom and bowling green before 1699.[32] Pepys took dinner at the Kings Head in 1667. Other establishments before 1700 included the Golden Ball and the Crown.[33] As communications improved, in 1684 the London Gazette announced that the post would go between London and Epsom during the season for drinking the waters.[34] This was the first daily post outside London and could well have resulted in the earlier visits of Celia Fiennes to Epsom.

Sixteen seventy nine saw the publication of a novel "News from Epsom or the Revengeful Lady" by Poor Robin. Illustrative of the moral value systems and attitudes of the time, it is a story of sexual conquest and betrayal, followed by revenge. It is reproduced as an appendix to this chapter. Home (1901) describes it as "so revolting that it seems inconceivable that it should have ever been published"[35] Home's comment provides an interesting look into changing attitudes to issues of sexuality.

In a contemporary Treatise on Mineral Waters (1684), Epsom waters were recommended as a purge in preparation for a major programme of taking the waters at a spa, indicating that other spas such as Islington were prospering and competing for Epsom's patronage. Summer was considered the best time to take the waters and a dog day was especially appropriate. Dog Days were considered the hottest in the year and were believed to have been the result of Sirius rising with the sun and adding to its heat (about 3 July to 11 August).[36]

As a rebuff to the competition, in 1684 a broadsheet was published entitled: An Exclamation from Tunbridge and Epsom against The Newfound Wells at Islington. This warned readers to beware of interlopers, counterfeit waters and Quack Doctors and was issued to thwart spa entrepreneurs elsewhere.[37] This was a portend of things to come. The same year saw Lady Evelyn securing the right to hold a Friday market and two fairs a year each of three days. Later Livingstone the apothecary was to lease the concession.[38] Epsom was part of the spa circuit by this time. Sir John Raresby brought his family to Epsom in 1686 and 1688 having in earlier years resorted to Scarborough and Buxton.[39]

By now there was a trade in Epsom waters that extended into the surrounding towns and villages. An account book survives for a Chertsey household for the years 1668 and 1669. These are assumed to be that of Edward Nicolas. In it, under "Charges General", are recorded references to the fetching of water from Epsom during the winter period.[40]

1688

24 Dec. for fetching Epsome watter - £0-2-6

27 Dec. for Epsom Water - £0-1-0

29 Dec. for fetching epsome water - £0-2-0

1689

10 Feb. Epsome water that Souch fetch - £0-1-0

28 Feb. Goodman Souch for Epsom Water - £0-1-0

The chronicles of Celia Fiennes' journeys have great significance for Epsom historians. This intrepid lady, who rode side saddle through England at the passage of the seventeenth to the eighteenth century, recorded Epsom in a state of transition. Unlike the other spas that she visited she made two detailed accounts of her visits. The first, sometime in the 1690s, chronicled Epsom as an undeveloped spa with minimal facilities. The second visit, probably about 1712, saw Epsom as a developed spa with new facilities, which completely changed the atmosphere of the town for her.[41]

In Celia Fiennes' early tours which took place in the 1690s, she compared Epsom with Barnet and complained that the spring was not a "quick" spring (i.e. of running water) like Tunbridge and Hampstead Spaw. At Barnet visitors went down to the water which was full of leaves and dirt. She disliked Barnet and, by implication, Epsom. Further comment was made of the "Sulpher Spaw Epsome" a little later when she compared it with a spring at Canterbury. She commented on the walled-in well liking "no spring that rises not quick and runs off apace". Further remark comes when she compared Epsom with the springs on Blackheath. Like Epsom, she thought the springs were very quick purgers due to alum.[42]

4.4 In South Street nos. 73-75 are considered to be brick fronted buildings dating from c.1675. The later Stuart shop front extension survives today.

Later Celia Fiennes expanded her description of Epsom with a narration that also emanated from the 1690s. She described Epsom Well as having waters from alum [43] with no basin or pavement and a dark interior. The spring was often drunk dry and water from elsewhere used to replenish the supply. The efficacy of the water was reduced however unless visitors could consume the waters before they were replenished. There was brick paving around the well to walk in wet weather, where sweetmeats and tea could be consumed. Celia disliked the whole arrangement, likening it to a dungeon, and would not choose to drink there. Near the house which contained the well there was a walk of trees which she considered not particularly pleasant. She noted that most people drank the water at home and that there were lodging and walking facilities in the town.

Accurately dating Celia Fiennes' early comments is difficult. In her account of Barnet and Epsom she referred to the "Earle of Maulberoug". This account is certainly dated before 14 December 1702 when the Dukedom of Marlborough was created.[44]

Further confirmation that these accounts predate 1702 comes from the fact that Lord Berkeley's House, Durdans, is mentioned. It was built with materials from Nonsuch Palace. Berkeley died in 1698 and his son sold the house to Charles Turner in 1702.[45] The narration must predate this, but post date 1684 when Sir Robert Howard built Ashtead House, which she also mentioned.[46] Furthermore, Celia failed to mention the Assembly Rooms which were mortgaged in 1699, suggesting a date prior to this.[47] We are left with a date probably in the early 1690s.

It is apparent that Celia, who had a great interest in mineral springs and wells, disliked Epsom Wells at the time. It was the source that later became known as the Old Wells which she visited. Epsom, like the other spas, was poised to launch into a new era of investment and prosperity. The Wells on the common were still offering only basic facilities and the town remained congested in the season with accommodation stretched. Some amusements were catered for but these remained relatively unsophisticated. The social scene had developed and alongside this the scandals and frolics of the visitors provided ample opportunity for literary amplification. As competition between the spas intensified so did the demand for improved tourist amenities. The proximity to London rendered the town a venue for weekend trips and day excursions. Epsom was ideally positioned for further intensification of commerce to provide an enhanced resort for relaxation, amusement and medicinal healing as the eighteenth century approached. Yet it was already one of the great watering places of the south alongside Bath and Tunbridge when Celia Fiennes recorded her first observations. With the onset of the 1690s much was to quickly change....

Appendix:

"News from Epsom

OR THE

Revengeful Lady

shewing how a Young Lady there was beguiled by a London Gallant & who when he had done boasted of a conquest For which unworthy deed she Wittily reveng'd and made a Capon of a Cockny

A Novell by Poor Robin - Kt Vindicta[48]

Printed 1679

The Revengeful Lady Or The Tell-Tale, EUNUCH’D

There was a Gentleman in this Town of a compleat Wit, and pleasant behaviour, a Person very fortunate in the Love of Women, and in all respects very Oblieging towards them, save that he wanted the government of the Tongue; for no sooner could he receive a Closet-kindness from his Mistress, but he would instantly boast of his success, and that with such Circumstances as added most to the glory of the Conqueror, without any regard to the Reputation of the Vanquished; which dissolute kind of carriage, as it could not but be taken very unkindly from the Ladies, so at last it proved very unfortunate to himself.

Going this Summer to Epsom, whether for the delightsomness of the Ayr, the benefit of the Waters, or the pleasure he took in the Company, I know not, nor is it material; but being there he became acquainted with a young Lady, beautiful in her Person, and pleasant in her Conversation. This Spark of London, had scarce been twice in her company, but from the success he had always met with, he concluded her his own, and accordingly suiting his addresses to his confidence, he apply'd himself to her in a more familiar way then became the slenderness of his acquaintance, or the nature of his pretence: which attempt so far incens'd her, that if ever he should offer the like incivility again, she protested he should never see her more.

He somewhat surprised with the unusual, (and therefore unexpected) coyness, had a months mind at one time to have called her proud slut, and to have Antidated her thereat by leaving her immediately; But upon better consideration on, finding so much beauty in her scorn, and Majesty in her anger, he thought it more pollicy to disemble his present resentment, then to frustrate his future hopes, and therefore in excuse of himself, he began to swear very liberally, That he offered that rudeness only to try her modestly, he confessed he had sometimes made use of those Town-fooleries for the Diversion of such as lik'd the humour, but for his part he neither hop'd nor believed that a person of her Circumstances could be pleas'd with such a kind of Daliance; alluring her withal (as far as Damm'd would do it) that in complyance with those strict rules of Chastity she profest to walk by, he would never for the future speak or any act any thing but what might correspond with the must unblemish'd Vertue Which protestations of his somewhat cleared up her clowdy Brow: and tho' she could hardly be friends with him that Afternoon, yet she told him upon his better behaviour for the future, that he might still hope not to be turned out of her service, Hereupon our gallant began to proceed with more Caution in his designs and to bear a greater respect to her that formerly, behaving himself so modestly in his expressions, and so obligingly in his actions, that he gained a more than ordinary effect from his Dearest, and he had at last so far won upon her by the artificial disguise of chastity, that she would many times trust herself alone with him in her chamber, at hours so unseasonable, as might have created a suspicion of any Womans vertue but hers. This when our vigilant youngster had perceived, he thought it in vain to dally any longer, resolving to take the Fort by Treachery, if he could not do it by Treaty, and in order thereto concluded upon the following Adventure.

Prevailing with her one day to take a walk in the Park, and coming to a shady bank (no matter for the purring Streams, and Warbling Choristers,) they sat down in a place very agreeable to the innocence of her design, and but too convenient for the immodesty of his: I could tell you a great deal of prittle prattle they had, but that one cross Reader or other will be so inquisitive to ask how I came to hear it. But Discourse they had, that's certain and 'tis a hundred to one but that t'was one Love Story or other; for at last it came to this: The young Gentleman gathering a blade of Grass, and applying himself to the Lady, ask'd Her if she could break it with Her hands: There's no question to be made, but reply'd Yes: But without many it's and and's, it came to a wager (which the most judicicus affirm to be a Bottle of Claret,) that he would tye her Thumbs so fast with it, that neither by the strength of her Arms or her wit, she should be able to break or untye it: This concluded on, he palm'd a Green Ribbon upon her, made so artificially like a blade of Grass, that it could very hardly be distinguished, and with this ty'd her Thumbs so firmly, that to her great admiration she was forced to confess the Wager lost: but he like a fair Gamester to give her a revenge, offered another botele, that if she would suffer him to put her arms over her head, she could not kiss her Elbow. Loosers you know play commonly without fear or wit, for she had no sooner consented, but she found not only the wager lost, but something else she valued I can't tell how much more, in a great deal of danger; for the Adventurer taking her at this advantage, began to use a forced dalliance, and to apply himself to her in a pritty familiar way that he had, which I shall leave every man to guess at, by what he would have done had he been in his place.

As to the Ladies I know they be warranting the sadness she was in, and at the same time both pittying her and envying her Condition. Therefore to disappoint neither one nor the other, the story says they cried out Murder, but withal that she Dyed only in the phrase of modern Poets; for she quickly came to herself again, being only a little over-heated, like a Colt newly back'd, by endeavouring to throw her Rider and complaining of a flushing she had in her face, she was forced to desire her Gallant (unkind as he was) to Unlace her Gown, and to give her the benefit of the air, bitterly upbraiding him all the while with the baseness of the action: what have you done quoth she, inhumane Ravisher ingrateful wretch that you are to first to bind me, and then to rob me of my greatest Treasures. He not caring to make much ado about nothing prethee be quiet (says he) and I'le repay thee with interest, look you do then: replied the tender-hearted soul, and so giving him her hand, they walked very lovingly home again perticipate of her loosings.

Hereto all was well, and like enough to continue so, if this bubling Coxcomb could but have held his tongue but he had the vanity of some other (indeed most) Gallants whose humour is so far from concealing any successful amour, that they will boast of kindness they never received, rather than not gain the reputation of being debauc'd: so he, big with the conceit of what he had done, found an opportunity (or indeed made one) of telling the whole adventure the same evening to an old Crony of his that had been a constant admirer of his continued success. This Gentleman, it seems had been the ancient servant of the Ladies I mean had attempted to debauch her for a long time, and therefore upon the relation of the whole matter, the person being named, and the action described at large, it is but rational to suppose him a little concern'd, not only that he should be disappointed in his hopes, but out-done at his own weapon: and to manifest that he was so, though he seemingly Laugh'd at the pleasantness of the adventure, yet he resolved, upon the first opportunity, to discover the abuse if it were a Lye, or if truth, to put in for the later-match of her affection.

The day following, meeting with her either by search or accident, though she never cared for his company or address, he prevailed with her by some importunity to hear this unwelcome story, which she did with great impatience and amazement, and though at first she was highly surpriz'd, yet having a womans wit, and being a little helped by the impertinance of the Relator, she gained time to recover her senses well enough to persuade him the story was false, resolving at the same time to cry quits with Mr Tell Tale when time should serve, but for the present not to seem to take notice of the Discovery.

And for a day or two after pretending a greater fondness to her Gallant for the sake of what had past, it was now her turn to desire him to take a walk to the same place they were at the other day, in which he readily consented, and I defie the crossest Reader in Christendom to suppose otherwise. Being come to a place she chose as most convenient for the design in hand, she desired him to sit down, and after a little amorous impertinance thus began to insinuate with him: Love, says she, shall I tye thy hands as thee did mine the other day, but you are so strong I'le do it with my Garter instead of your Grass, this was easily consented to: Ah you Rogue, continued she, I'le tye your Legs too, 'twill be no hindrance, Sirrah; Ha this was but a modest request; Now my Dear, says she, put your hands over your head as I did; that done, she takes and opportunity to tye them fast to the stump of a Bush; the Fellow all this while pleased with the Conceptions he had of the amorous Stratagem, lay stock still, absolutely imagining her design to be much like his, in what resemblance the diversity of the Sex was capable of;

But, silly Ass, he found himself damnably deceived, for by the austerity of her countenance, he found anger a passion more predominant in her than Love, especially when she began to threaten him in a more unpleasant dialect then perhaps became either her Sex or quality; for though in civility we may call it chiding, in plain terms 'twas no better nor worse then downright scolding; The names she had dissembled over but even now, she again repeated, but in such a tone as quickly gave him to know the difference; Now Sirrah, says she, you Rogue you, I'le teach you to Kiss and tell; could you not be content to debauch me, but you must Scandalize me to rob me not only of my vertue, but likewise of my good name; I'le make an Example for all such Villains as you are.

More she said to this purpose as near as I can guess, (for to tell you the truth I did not hear her) and to make her words good she drew out a very sharp Pen-knife, now, says she, what would you think Mister Cockny if I should make a Capon of you? And hang me if I don't shew that Londoner such a trick he shall remember the Country all days of his life; with that she gave him such a touch of love, in the part that your Almanack-makers call Scorpio, and your Anatomists Scrotum that it is verily said by sober personages, that he never had a mind to Wench after: so rising up from the poor Eunuch the Ironical Baggage did so taunt at him that some writers affirm it went to the very heart of him: alas Sir, says she, how you bleed! What are you wounded? I fear you have been fighting for my sake, I have a pair of Blood-stones here, pray take 'em and hang 'em about your Neck, while I run and send you a Chyrurgion, which it seems she did in kindness to herself, not to him;

The Chyrurgion making a speedy cure of his Wound, the Lady at the same time, in some measure, salved up the wounds of her reputation, for she hath sealed up the mouth of the Actor so close, that 'tis generally believed he will speak no more of this matter; so that so the story be very true, in the general as I have related it, yet as to the particular persons concerned, I desire you would not urge me to the discovery of them, for I protest I know not who they are."

Dr Bruce E Osborne

Developments, visitors, reputation, demise of Nonsuch, Appendix: News from Epsom.

The 1660s saw Epsom embarking on a period of prosperity as a significant health resort combining the pursuit of health with the pursuit of leisure. There are hints of stagnation as the 1690s approached, soon to be rectified with the onset of the new century.

4:1 Schellinks drawing of Epsom Well, 1662./ Samuel Pepys.

In 1662 we have the earliest known illustration of Epsom Wells. The detail includes a small building located on an otherwise undeveloped common with scrub interspersed by people congregating around the well. In the bushes are those whose imbibing of the waters was giving rise to the renowned purging effect. What is apparent is that the facilities were severely limited. William Schellinks, the artist who drew this early picture of Epsom Well, described the location in his travel journal.[1] He was one of three artists commissioned by Laurence van de Hem, son of a prosperous Dutch merchant, to record the scenery of Europe.

Schellinks visited the well on four separate days. In the account which follows, the present author's comments are in square [ ] brackets.

"On the 5 June [1662] at 9 o'clock in the morning we walked with Mr Pelt from Kingston to Epsom, being 5 miles. We got there midday, and went to stay at one Robin Bird, and were there well accommodated. Epsom is a very famous and very pleasant place, much visited because of the water, which lies in a valley not far from there, which is much drunk for health reasons, because of its purgative powers, and which is being sent in stoneware jars throughout the land. [these would likely be similar to the German "Kruke, irdener Krug", made of clay and often impressed with the provenance of the contents, to date no recorded example has been identified from Epsom although the Science Museum has one from Godstone in Surrey for Iron Pear Tree Water, circa 1750/60 [2]] It is a well, and with a wall around raised as a well head, and there is ground paved with bricks. In the middle it has an opening in the ground for the water flow, and the well water, reckoned from there, stands ten spans high and eight spans from the brick floor. [a span is generally reckoned to be 9 inches, this makes the depth of water from the floor 6 feet and the height of the wall surrounding the well 18 inches] This well stands at the back in a small house, in which there are some small rooms, and many people come in there to drink and to shelter from the sun. For this well a yearly rent of twelve pound sterling is paid, which is given to the poor. Those who come to drink the water give to the person who draws it as much as they wish. Now in 1662 an old man and woman have it on hire. [this point is confirmed by Samuel Pepys in 1667]

The practice of drinking the water is from early in the morning until 8, 9, or 10 o'clock. It is drunk on an empty stomach from stoneware mugs holding about one pint. Some drink ten, twelve, even fifteen or sixteen pints in one journey, but everyone as much as he can take. And one must then go for a walk; it works extraordinary well, with various funny results - probatum est. Gentlemen and ladies have here separate meeting places, putting down sentinels in the shrub in every direction. It has happened that the well was drunk empty three times in one morning; in hot and dry summers, when the water does not get any feed from above, but has to work up from the lower parts of the ground, it has more strength, and the people who observe this come then in such crowds that the village which is fairly large and can spread at least 300 beds, is still too small, and the people are forced to look for lodgings in the neighbourhood. [Pepys went to Ashtead the following year] Some stay there on doctor's orders for several weeks continuously into the middle of the summer, drinking daily from this water, and many people take some hot meal broth or ale after drinking the water. I have added hereto my drawing of the described place." [see front illustration]

Schellinks goes on to recount an experience that night. A disturbance in the house was thought to be thieves and the alarm was raised. It transpired that it was a wayward pig that had strayed into the kitchen only to be redirected by the maid. The travelling companions spent the rest of the night in the same bed for security.

"On the 6 June in the morning we went to the water well, and each drank three or four pints of water, as much as the day before, and went for a walk, and at 11 o'clock we returned to Kingston, where we arrived at 2 o'clock....

....to Kingston, and at 5 o'clock I went on foot with Mr Thierry once more to Epsom; on the way we bought a fat goose for 16 pence and had it roasted at our lodgings, where we stayed again, which was not at all bad.

The 11th June at 7 o'clock in the morning we went again to the well and found there again much company, on foot and on horseback, gentlemen, ladies, men and girls, Dutch, French, etc. [this confirms an international tourist trade] We drank six large pints of the water and then went for a walk, but the whole result was but one stool. To follow the fashion we went to our lodging to take there some bread and meat broth. In the afternoon we went to explore the countryside all around, which was very pleasant.

On the 12 June in the morning we went again to the well and found again a lot of people. After having broken our fast with the water we went to wash it down with a cup of warm ale and so went from Epsom to the wonderful place of Lord Berkeley, which is extraordinary pleasant, the house as well as the garden. [Durdans which features extensively in the early history of Epsom] The place has a very excellent avenue with many large trees, and a very beautiful gatehouse. Amongst other rooms we saw a very beautiful one full of paintings, and others richly furnished, also a fine chapel and a large hall etc. The garden is very pleasant because of natural hills and dales, adorned with fountains, sculptures, cypress trees, a maze, wildernesses, grottoes, bowers, avenues or walks, summerhouses, a bowling green etc., all in Italian style." [3]

Durdans was a substantial house at this time and of considerable local importance. In the 1650s it was the home of Sir Robert Coke, Lord Chief Justice who had married a Berkeley. George, the ninth Earl Berkeley inherited the house in 1652 and it became a mecca for high society. It was rebuilt using the materials from Nonsuch Palace shortly after Schellinks visit in 1662, only to be burnt down and again rebuilt in time for Celia Fiennes in the 1690s. Little record remains of this earlier house, it was the later one that was seen by Celia Fiennes and recorded in her first account of Epsom.[4] Epsom was a town of some prestige by this time. In 1662 George, Earl Berkeley, entertained Charles II at Epsom with his brother and Samuel Pepys.[5] John Evelyn the diarist, met the King and Queen, the Duke and Duchess of York, Prince Rupert and various noblemen on this occasion.[6] Charles II incidentally came again to Epsom in 1664.

The Berkeleys were the keepers of Nonsuch Palace endorsing the constant associations between Epsom and Nonsuch. From Schellinks' description of Durdans, it is worthy of note that the Renaissance Italian influence, which was so important in the conceptualisation of Nonsuch Palace, was also adopted at Durdans; perhaps the creators of Durdans sought to replicate the ambience of the celebration of mythology and water noted at Nonsuch.

The arrival of Samuel Pepys on July 25th 1663 was not without problems. Pepys noted that the town was full and had to lodge in Ashtead, an experience that came in for some criticism due to the quality of the accommodation. Visiting Ashtead gave him an opportunity to visit his cousin whose house was not as grand as he recalled as a child. Ashtead was only one mile from the Old Wells, about two from Epsom town. Pepys noted the surprising number of people in Epsom, including some people of quality, with little else to do but drink the water. Epsom town centre facilities, like those at the wells, were clearly limited at this time.[7]

The year 1663 saw the ballad Merry Newes from Epsom Wells launched which gave interesting insights into social life at Epsom.[8] The plot is about a lawyer who has a fling with a goldsmiths wife, while the lawyers wife is collecting the Epsom water. A calamity ensues and the lawyer, after making a speech leaves town. The drinking of Epsom Water appears synonymous with licentious behaviour. The following is an extract from the full text.

4.2 When the back is turned, early cartoon.

"The lawyers wife, with famous hands

the chamber door doth make fast.

It grieved her sore to face the whore

had got away her breakfast.

She opes the casement, and she calls

all people to the slaughter.

How most unluckily it falls

his wife should watch his water.

To save his life he takes his wife

and out of town he trudges

the lawyers fact, is censured by

almost a thousand judges.

They flout and sneer, they jest and jear

the town is full of laughter

But many of them that were there

had paddled in such water.

Away he goes, filled full of woes

to think what will come after

He that loves life, let him keep his wife

from drinking Epsom Water."

Also in year 1663, Richard Evelyn, brother of the diarist, became lord of the manor.[9] Also about this time, according to the Epsom Commons Association, a roughly circular area around the Old Well was cleared and rights of common were curtailed. This encroachment of the manorial commons enabled the crowds to be accommodated, and being a purging well, meant that the area surrounding the spring was not contaminated by the inevitable pollution. The area was 40 rods in radius, about 450 yards in diameter and can be identified on nineteenth century maps. The earliest map showing this is the 1866 25 inch OS map.[10] It does not appear on the first edition OS map of 1810-17. This enclosure was later to determine the incongruous area of mid-twentieth century urban housing now surrounding The Wells. The avoidance of one pollution subsequently precipitated another!

The fact that Epsom provided an easily accessible resort from London is apparent in 1665 when Richard Evelyn, JP. and lord of the manor, was obliged to close the wells due to possible spread of infection from the Great Plague.[11] The instruction, issued by the Surrey Quarter Sessions, directed that the wells be locked and no person permitted to drink the waters. This may also have been the consideration behind the clearing of the circular area around the well mentioned in the previous paragraph. The legal instruction noted that there had been a substantial influx of visitors to the town from London on the pretext of drinking the waters, no doubt to escape the ravishes of the plague.[12] By modern day standards Epsom was a small settlement in spite of its visitor numbers and it is difficult to appreciate the intimacy that must have existed compared with the impersonal indifference that features in modern day urban society.

By 1667 Samuel Pepys was back in Epsom. He left London at five in the morning to journey to the wells to drink the mineral water at the appropriate time, as well as to fill containers to take home. At the well he learnt from the woman attendant that the well was rented from the lord of the manor for £12 a year, thereby confirming the earlier information recorded by Schellinks.[13] Pepys wrote in his diary in July, "To Epsum by eight o'clock, to the well; where much company, and I drank the water: they did not, but I did drink four pints. And to the towne to the King's Head; and hear my Lord Buckurst and Nelly (Nell Gwynne) are lodged at the next house, and Sir Charles Sedley with them: and keep a merry house."[14]

4.3 Charles II with Nell Gwyn. Melville 1923.

4.3 Charles II with Nell Gwyn. Melville 1923. Lewis Melville (1923) provides interesting background to this amorous rendezvous. Nell Gwyn was without doubt a woman with qualities that attracted men, apart from a reputation of running up huge bills on account. Charles Sackville, Lord Buckhurst, afterwards sixth Earl of Dorset and first Earl of Middlesex was for a while the acknowledged lover of Ms.Gwyn. On May Day in 1667 Pepys had seen Nell in her lodgings in Drury Lane, London. Buckhurst about this time started his amorous adventure with the lady, taking her to Epsom to remove her from the theatrical circles within which she circulated. Pepys expressed concern that Nell was leaving the theatre where she gave great pleasure to audiences with her charm. By August Nell was back in London at the Kings House where she played Cydaria in "The Indian Emperor”. This appears to have been the closing stages of the Buckhurst love affair and it is interesting to note that Buckhurst was sent to France by the King on a fool’s errand the following Christmas and made Earl of Middlesex. By January 1668 Charles II was liaising with Nell Gwyn and it appears that an amorous affair had been in the offing some weeks previous. This would explain the position of Buckhurst. The King thereafter commandeered Nell’s attentions at the expense of Lady Castlemaine who he "compensated” in 1670 by making her Baroness Nonsuch, Countess of Southampton and Duchess of Cleveland, and at the same time giving her Nonsuch Palace. The King’s affair with Nell was to have longevity, when he died in 1685 she sincerely mourned his demise.[15]

As Samuel Pepys no doubt found out, drinking 4 pints of mineralised water was a daunting prospect. In the Bohemian spas a custom arose of eating a wafer while taking the waters. This custom remains to this day and the "Kolonada Luxus" continues to be produced locally. Bath became noted for its Bath Oliver biscuits as a result of the efforts of Dr Oliver to make the waters more palatable. Such a practice likely took place in Epsom in order to render the waters more palatable. A wafer iron in the Guildford Museum lends credence to this belief.

In the same year as Pepys' later visit, 1667, two convictions for running a disorderly house and another for keeping an unlicensed common tippling house were recorded.[16] Things were without doubt lively in Epsom but it was not only at the spa that one could be relieved of ones money. A popular misconception is that it was customary for travellers between London and Epsom to be waylaid. The people of Tooting had a reputation for what became almost extortion in an effort to foist their goods and services on the trippers. Such a practice gave rise to the expression "tooting" or "touting".[17] The truth is that to tout was first recorded about 1700 and was to peer at or look out for, this particularly applied to watching a horse for betting purposes. The maligned people of Tooting were in fact named after the ancient peoples of "tota”. Although this plausible legend is false, it is suggestive of the character of the times and the practice of touting has application in many modern tourism resorts as well as likely taking place on the roads to Epsom. Touting and Tooting were perhaps just an unfortunate coincidence of vocabulary.

As the seventeenth century progressed, the year of 1668 saw a number of minor occurrences that give an insight into the activities at the spa. Many doctors advised a visit to Epsom, and the Court of Charles II and other fashionable people visited the town.[18] In Pepys' domestic papers are letters from John Owen requesting 12 days leave to visit the Epsom Wells in June followed by a further request in August.[19] The Court Rolls record that the wall erected by Richard Evelyn around a well near the main Well had been broken down and this was prejudicial to those taking the waters. This suggests more than one well and that the one mentioned was under the control of the manor.[20]

In 1670, Nonsuch Palace was given by Charles II to Barbara Villiers, who rapidly demolished it. The ruins of Nonsuch were subsequently used to construct the buildings in the town. Thereafter there was no royal palace in the locality of Epsom.[21] Shadwell's comedy, Epsom Wells, began a long run at the Duke's Theatre in 1673, having been written the year before. Epsom was portrayed as a place of licentious behaviour and scandalous goings on.[22] This suggests that Epsom society had moved "downmarket" perhaps following the demise of Nonsuch Palace and abandonment by the aristocracy. Brighton followed a similar sequence in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Initially it attracted the aristocracy of the Regency period and the Royal Pavilion was built. Later Royalty went elsewhere and the town became a centre for entertainment and pleasure, much of it of a dubious nature.[23]

4.4 Shadwell's 17th century Epsom Wells, performed in 2001 by the Ralph Richardson Memorial Studios, Wood Green, directed by John Tarlton.

Another unfortunate event in 1670 was the demise of Richard Evelyn, lord of the manor, who died early in March from calculus, a concretion found in the body. John Evelyn, the diarist, records that his brother's body was opened and a stone not much bigger than a nutmeg was removed from his bladder. In addition his liver and kidneys were faulty, accounting for the intolerable pain that Richard experienced before death. The suggestion is that he died of over consumption of Epsom Waters, having drunk them when in good health, thereby no doubt reducing Lady Elizabeth Evelyn's enthusiasm for the waters.[24] John Evelyn came to Epsom for the funeral.[25] Following her husband's death, Lady Evelyn took over the manorial responsibilities. Elizabeth Evelyn, as lady of the manor, held courts from 1670 to 1691.[26] In the same year, 1670, as a result of a dispute with tenants, she caused the spring to be stopped up, but a new well was discovered at Slyfield, 4 to 5 miles away in Stoke D'Abernon, in 1671. Soon after, the original well at "Ebsham" was reopened with houses to accommodate the reception of strangers.[27] In 1675 the Court Baron recorded that a building solely for the purpose of taking the waters was to be erected on the common annexed to the public wells.[28]

The provision of games and entertainment facilities was important to any developing spa resort at the time. Bowling was popular on outdoor greens and Epsom made provision for the game. William Head of the Kings Head purchased an acre of land adjacent to the bowling green in 1671. This indicates that the lower bowling green, later noted by Celia Fiennes, was in existence by this date. In 1678, William Glover, the bowling green owner, had died leaving a bowling alley on 2 acres known as Phillips Close. It abutted the Kings Head on the east and the High Street on the north and west. It was therefore on the south side of the present High Street opposite the Clock Tower. The green proved successful and attracted substantial custom from the 1680s.[29] A survey of 1688 reveals a further bowling green at Epsom. George Richbell, a yeoman, owned a meadow close to a bowling green. The location was near Summersgate Lane, now Wheeler's Lane, and Clay Hill now West Hill. It was not particularly successful and is not mentioned by contemporary writers. Last record of it was in 1727 when it was described as a former bowling green.[30] The second green was taken over in 1688 by Ashenhurst, who also had an interest in the other. Having secured a monopoly, he closed the second green.[31]

Indications are that an infrastructure to accommodate and entertain visitors was being developed by the 1670s in Epsom. The New Inn was mentioned in the Court Baron of 1672. Another of similar name subsequently became the White Horse in Dorking Road and not to be confused with the later Waterloo House in the High Street. Waterloo House was known as the New Tavern and likely had a longroom and bowling green before 1699.[32] Pepys took dinner at the Kings Head in 1667. Other establishments before 1700 included the Golden Ball and the Crown.[33] As communications improved, in 1684 the London Gazette announced that the post would go between London and Epsom during the season for drinking the waters.[34] This was the first daily post outside London and could well have resulted in the earlier visits of Celia Fiennes to Epsom.

Sixteen seventy nine saw the publication of a novel "News from Epsom or the Revengeful Lady" by Poor Robin. Illustrative of the moral value systems and attitudes of the time, it is a story of sexual conquest and betrayal, followed by revenge. It is reproduced as an appendix to this chapter. Home (1901) describes it as "so revolting that it seems inconceivable that it should have ever been published"[35] Home's comment provides an interesting look into changing attitudes to issues of sexuality.

In a contemporary Treatise on Mineral Waters (1684), Epsom waters were recommended as a purge in preparation for a major programme of taking the waters at a spa, indicating that other spas such as Islington were prospering and competing for Epsom's patronage. Summer was considered the best time to take the waters and a dog day was especially appropriate. Dog Days were considered the hottest in the year and were believed to have been the result of Sirius rising with the sun and adding to its heat (about 3 July to 11 August).[36]

As a rebuff to the competition, in 1684 a broadsheet was published entitled: An Exclamation from Tunbridge and Epsom against The Newfound Wells at Islington. This warned readers to beware of interlopers, counterfeit waters and Quack Doctors and was issued to thwart spa entrepreneurs elsewhere.[37] This was a portend of things to come. The same year saw Lady Evelyn securing the right to hold a Friday market and two fairs a year each of three days. Later Livingstone the apothecary was to lease the concession.[38] Epsom was part of the spa circuit by this time. Sir John Raresby brought his family to Epsom in 1686 and 1688 having in earlier years resorted to Scarborough and Buxton.[39]

By now there was a trade in Epsom waters that extended into the surrounding towns and villages. An account book survives for a Chertsey household for the years 1668 and 1669. These are assumed to be that of Edward Nicolas. In it, under "Charges General", are recorded references to the fetching of water from Epsom during the winter period.[40]

1688

24 Dec. for fetching Epsome watter - £0-2-6

27 Dec. for Epsom Water - £0-1-0

29 Dec. for fetching epsome water - £0-2-0

1689

10 Feb. Epsome water that Souch fetch - £0-1-0

28 Feb. Goodman Souch for Epsom Water - £0-1-0

The chronicles of Celia Fiennes' journeys have great significance for Epsom historians. This intrepid lady, who rode side saddle through England at the passage of the seventeenth to the eighteenth century, recorded Epsom in a state of transition. Unlike the other spas that she visited she made two detailed accounts of her visits. The first, sometime in the 1690s, chronicled Epsom as an undeveloped spa with minimal facilities. The second visit, probably about 1712, saw Epsom as a developed spa with new facilities, which completely changed the atmosphere of the town for her.[41]

In Celia Fiennes' early tours which took place in the 1690s, she compared Epsom with Barnet and complained that the spring was not a "quick" spring (i.e. of running water) like Tunbridge and Hampstead Spaw. At Barnet visitors went down to the water which was full of leaves and dirt. She disliked Barnet and, by implication, Epsom. Further comment was made of the "Sulpher Spaw Epsome" a little later when she compared it with a spring at Canterbury. She commented on the walled-in well liking "no spring that rises not quick and runs off apace". Further remark comes when she compared Epsom with the springs on Blackheath. Like Epsom, she thought the springs were very quick purgers due to alum.[42]

4.4 In South Street nos. 73-75 are considered to be brick fronted buildings dating from c.1675. The later Stuart shop front extension survives today.

Later Celia Fiennes expanded her description of Epsom with a narration that also emanated from the 1690s. She described Epsom Well as having waters from alum [43] with no basin or pavement and a dark interior. The spring was often drunk dry and water from elsewhere used to replenish the supply. The efficacy of the water was reduced however unless visitors could consume the waters before they were replenished. There was brick paving around the well to walk in wet weather, where sweetmeats and tea could be consumed. Celia disliked the whole arrangement, likening it to a dungeon, and would not choose to drink there. Near the house which contained the well there was a walk of trees which she considered not particularly pleasant. She noted that most people drank the water at home and that there were lodging and walking facilities in the town.

Accurately dating Celia Fiennes' early comments is difficult. In her account of Barnet and Epsom she referred to the "Earle of Maulberoug". This account is certainly dated before 14 December 1702 when the Dukedom of Marlborough was created.[44]

Further confirmation that these accounts predate 1702 comes from the fact that Lord Berkeley's House, Durdans, is mentioned. It was built with materials from Nonsuch Palace. Berkeley died in 1698 and his son sold the house to Charles Turner in 1702.[45] The narration must predate this, but post date 1684 when Sir Robert Howard built Ashtead House, which she also mentioned.[46] Furthermore, Celia failed to mention the Assembly Rooms which were mortgaged in 1699, suggesting a date prior to this.[47] We are left with a date probably in the early 1690s.

It is apparent that Celia, who had a great interest in mineral springs and wells, disliked Epsom Wells at the time. It was the source that later became known as the Old Wells which she visited. Epsom, like the other spas, was poised to launch into a new era of investment and prosperity. The Wells on the common were still offering only basic facilities and the town remained congested in the season with accommodation stretched. Some amusements were catered for but these remained relatively unsophisticated. The social scene had developed and alongside this the scandals and frolics of the visitors provided ample opportunity for literary amplification. As competition between the spas intensified so did the demand for improved tourist amenities. The proximity to London rendered the town a venue for weekend trips and day excursions. Epsom was ideally positioned for further intensification of commerce to provide an enhanced resort for relaxation, amusement and medicinal healing as the eighteenth century approached. Yet it was already one of the great watering places of the south alongside Bath and Tunbridge when Celia Fiennes recorded her first observations. With the onset of the 1690s much was to quickly change....

Appendix:

"News from Epsom

OR THE

Revengeful Lady

shewing how a Young Lady there was beguiled by a London Gallant & who when he had done boasted of a conquest For which unworthy deed she Wittily reveng'd and made a Capon of a Cockny

A Novell by Poor Robin - Kt Vindicta[48]

Printed 1679

The Revengeful Lady Or The Tell-Tale, EUNUCH’D

There was a Gentleman in this Town of a compleat Wit, and pleasant behaviour, a Person very fortunate in the Love of Women, and in all respects very Oblieging towards them, save that he wanted the government of the Tongue; for no sooner could he receive a Closet-kindness from his Mistress, but he would instantly boast of his success, and that with such Circumstances as added most to the glory of the Conqueror, without any regard to the Reputation of the Vanquished; which dissolute kind of carriage, as it could not but be taken very unkindly from the Ladies, so at last it proved very unfortunate to himself.

Going this Summer to Epsom, whether for the delightsomness of the Ayr, the benefit of the Waters, or the pleasure he took in the Company, I know not, nor is it material; but being there he became acquainted with a young Lady, beautiful in her Person, and pleasant in her Conversation. This Spark of London, had scarce been twice in her company, but from the success he had always met with, he concluded her his own, and accordingly suiting his addresses to his confidence, he apply'd himself to her in a more familiar way then became the slenderness of his acquaintance, or the nature of his pretence: which attempt so far incens'd her, that if ever he should offer the like incivility again, she protested he should never see her more.

He somewhat surprised with the unusual, (and therefore unexpected) coyness, had a months mind at one time to have called her proud slut, and to have Antidated her thereat by leaving her immediately; But upon better consideration on, finding so much beauty in her scorn, and Majesty in her anger, he thought it more pollicy to disemble his present resentment, then to frustrate his future hopes, and therefore in excuse of himself, he began to swear very liberally, That he offered that rudeness only to try her modestly, he confessed he had sometimes made use of those Town-fooleries for the Diversion of such as lik'd the humour, but for his part he neither hop'd nor believed that a person of her Circumstances could be pleas'd with such a kind of Daliance; alluring her withal (as far as Damm'd would do it) that in complyance with those strict rules of Chastity she profest to walk by, he would never for the future speak or any act any thing but what might correspond with the must unblemish'd Vertue Which protestations of his somewhat cleared up her clowdy Brow: and tho' she could hardly be friends with him that Afternoon, yet she told him upon his better behaviour for the future, that he might still hope not to be turned out of her service, Hereupon our gallant began to proceed with more Caution in his designs and to bear a greater respect to her that formerly, behaving himself so modestly in his expressions, and so obligingly in his actions, that he gained a more than ordinary effect from his Dearest, and he had at last so far won upon her by the artificial disguise of chastity, that she would many times trust herself alone with him in her chamber, at hours so unseasonable, as might have created a suspicion of any Womans vertue but hers. This when our vigilant youngster had perceived, he thought it in vain to dally any longer, resolving to take the Fort by Treachery, if he could not do it by Treaty, and in order thereto concluded upon the following Adventure.

Prevailing with her one day to take a walk in the Park, and coming to a shady bank (no matter for the purring Streams, and Warbling Choristers,) they sat down in a place very agreeable to the innocence of her design, and but too convenient for the immodesty of his: I could tell you a great deal of prittle prattle they had, but that one cross Reader or other will be so inquisitive to ask how I came to hear it. But Discourse they had, that's certain and 'tis a hundred to one but that t'was one Love Story or other; for at last it came to this: The young Gentleman gathering a blade of Grass, and applying himself to the Lady, ask'd Her if she could break it with Her hands: There's no question to be made, but reply'd Yes: But without many it's and and's, it came to a wager (which the most judicicus affirm to be a Bottle of Claret,) that he would tye her Thumbs so fast with it, that neither by the strength of her Arms or her wit, she should be able to break or untye it: This concluded on, he palm'd a Green Ribbon upon her, made so artificially like a blade of Grass, that it could very hardly be distinguished, and with this ty'd her Thumbs so firmly, that to her great admiration she was forced to confess the Wager lost: but he like a fair Gamester to give her a revenge, offered another botele, that if she would suffer him to put her arms over her head, she could not kiss her Elbow. Loosers you know play commonly without fear or wit, for she had no sooner consented, but she found not only the wager lost, but something else she valued I can't tell how much more, in a great deal of danger; for the Adventurer taking her at this advantage, began to use a forced dalliance, and to apply himself to her in a pritty familiar way that he had, which I shall leave every man to guess at, by what he would have done had he been in his place.

As to the Ladies I know they be warranting the sadness she was in, and at the same time both pittying her and envying her Condition. Therefore to disappoint neither one nor the other, the story says they cried out Murder, but withal that she Dyed only in the phrase of modern Poets; for she quickly came to herself again, being only a little over-heated, like a Colt newly back'd, by endeavouring to throw her Rider and complaining of a flushing she had in her face, she was forced to desire her Gallant (unkind as he was) to Unlace her Gown, and to give her the benefit of the air, bitterly upbraiding him all the while with the baseness of the action: what have you done quoth she, inhumane Ravisher ingrateful wretch that you are to first to bind me, and then to rob me of my greatest Treasures. He not caring to make much ado about nothing prethee be quiet (says he) and I'le repay thee with interest, look you do then: replied the tender-hearted soul, and so giving him her hand, they walked very lovingly home again perticipate of her loosings.

Hereto all was well, and like enough to continue so, if this bubling Coxcomb could but have held his tongue but he had the vanity of some other (indeed most) Gallants whose humour is so far from concealing any successful amour, that they will boast of kindness they never received, rather than not gain the reputation of being debauc'd: so he, big with the conceit of what he had done, found an opportunity (or indeed made one) of telling the whole adventure the same evening to an old Crony of his that had been a constant admirer of his continued success. This Gentleman, it seems had been the ancient servant of the Ladies I mean had attempted to debauch her for a long time, and therefore upon the relation of the whole matter, the person being named, and the action described at large, it is but rational to suppose him a little concern'd, not only that he should be disappointed in his hopes, but out-done at his own weapon: and to manifest that he was so, though he seemingly Laugh'd at the pleasantness of the adventure, yet he resolved, upon the first opportunity, to discover the abuse if it were a Lye, or if truth, to put in for the later-match of her affection.

The day following, meeting with her either by search or accident, though she never cared for his company or address, he prevailed with her by some importunity to hear this unwelcome story, which she did with great impatience and amazement, and though at first she was highly surpriz'd, yet having a womans wit, and being a little helped by the impertinance of the Relator, she gained time to recover her senses well enough to persuade him the story was false, resolving at the same time to cry quits with Mr Tell Tale when time should serve, but for the present not to seem to take notice of the Discovery.

And for a day or two after pretending a greater fondness to her Gallant for the sake of what had past, it was now her turn to desire him to take a walk to the same place they were at the other day, in which he readily consented, and I defie the crossest Reader in Christendom to suppose otherwise. Being come to a place she chose as most convenient for the design in hand, she desired him to sit down, and after a little amorous impertinance thus began to insinuate with him: Love, says she, shall I tye thy hands as thee did mine the other day, but you are so strong I'le do it with my Garter instead of your Grass, this was easily consented to: Ah you Rogue, continued she, I'le tye your Legs too, 'twill be no hindrance, Sirrah; Ha this was but a modest request; Now my Dear, says she, put your hands over your head as I did; that done, she takes and opportunity to tye them fast to the stump of a Bush; the Fellow all this while pleased with the Conceptions he had of the amorous Stratagem, lay stock still, absolutely imagining her design to be much like his, in what resemblance the diversity of the Sex was capable of;

But, silly Ass, he found himself damnably deceived, for by the austerity of her countenance, he found anger a passion more predominant in her than Love, especially when she began to threaten him in a more unpleasant dialect then perhaps became either her Sex or quality; for though in civility we may call it chiding, in plain terms 'twas no better nor worse then downright scolding; The names she had dissembled over but even now, she again repeated, but in such a tone as quickly gave him to know the difference; Now Sirrah, says she, you Rogue you, I'le teach you to Kiss and tell; could you not be content to debauch me, but you must Scandalize me to rob me not only of my vertue, but likewise of my good name; I'le make an Example for all such Villains as you are.

More she said to this purpose as near as I can guess, (for to tell you the truth I did not hear her) and to make her words good she drew out a very sharp Pen-knife, now, says she, what would you think Mister Cockny if I should make a Capon of you? And hang me if I don't shew that Londoner such a trick he shall remember the Country all days of his life; with that she gave him such a touch of love, in the part that your Almanack-makers call Scorpio, and your Anatomists Scrotum that it is verily said by sober personages, that he never had a mind to Wench after: so rising up from the poor Eunuch the Ironical Baggage did so taunt at him that some writers affirm it went to the very heart of him: alas Sir, says she, how you bleed! What are you wounded? I fear you have been fighting for my sake, I have a pair of Blood-stones here, pray take 'em and hang 'em about your Neck, while I run and send you a Chyrurgion, which it seems she did in kindness to herself, not to him;

The Chyrurgion making a speedy cure of his Wound, the Lady at the same time, in some measure, salved up the wounds of her reputation, for she hath sealed up the mouth of the Actor so close, that 'tis generally believed he will speak no more of this matter; so that so the story be very true, in the general as I have related it, yet as to the particular persons concerned, I desire you would not urge me to the discovery of them, for I protest I know not who they are."

Click on website below to return to Index and Introduction.

Website: Click Here

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

1) TOPOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

England

3) INFORMATION CATEGORY:

Springs and Wells General InterestHistory & Heritage