|

|

The Holy Well

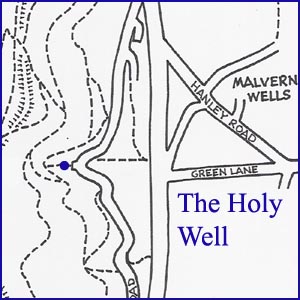

NGR 77087 42257

Site Number: C72

By Bruce Osborne and Cora Weaver (C) 2012

Area 5. Malvern Wells Area Springs and Wells

Malvern Hills, England

Description: a basin and flowing spout inside an ornamental building.

The drooping patient, scarce alive;

Where, as he gathers strength to toil,

Not e'en thy heights his spirits foil.

(Robert Bloomfield 1766-1823)

Early Visitors to the Holy Well

Three of the earliest references to Holy Well are found in the 1612 burial records of Great Malvern. Another reference appears in the Defford parish records, which record the death in 1613 of 'A poore man being a cripple who came from

The diarist John Evelyn recorded in 1654 how he "...deviated to the Holy Wells, trickling out of a vally thro' a steepe declivity towards the foot of the greate Mauvern Hill; they are said to heale many infirmities, as king's evil, leoprosie, sore eyes, etc." A similar reference to Holy Wells occurs in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1666.[4] Unfortunately the precise location is not identified in either case and so we are left to conclude that there may have been more than one Holy Well, possibly including St Werstan's Holy Well near the Malvern town centre.

As early as 1740 the famous Doctor Thomas Short wrote of Holy Well, which he described as free from steele and lathers well.[5]

Later in 1797, L. Andrews published his map of the Mineral Waters of England 'in accordance with the Act'. On this the Holy Well is the only Malvern source identified suggesting that it was the most important local well at the time.[6]

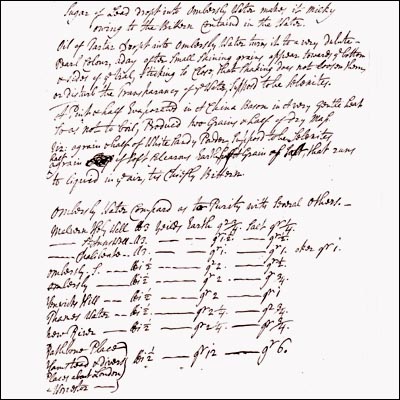

Dr John Wall was a 17th century Worcester physician who was familiar with Pyrmont waters and became a major influence in the development of Holy Well as a health resort. In 1743 he, together with apothecary William Davies, analysed the Holy Well water. In 1757 he published his much quoted analysis of the waters, in which the water was misleadingly observed to contain 'nothing at all'. Its mineral content was so low that it was pronounced pure. Holy Well water was unlike most healing waters, which rely on their mineral content for their healing properties, and this stimulated one wag to write the couplet:

Malvern water, says Dr John Wall,

Is fam'd for containing just nothing at all.[7]

Illustrated is a comparison, written in his own hand, between the waters of Holy Well and local waters, and others further afield.

Dr Wall retired to

Sacred to the memory of John Wall M.D. late of

Whose Body resteth Here

After a Life of Labour for the good of Others.

Nature gave him Talents

a Benevolent Heart directed y Application of them to the Study and practice of A Profession the most beneficial to Mankind, and By an uncommon Genius for Historie Painting; (An Amusement worthy his enlarged Mind) He has produced many lasting Evidences of the Noble simplicity of his Sentiments, and the Extensiveness of his Abilities Husbands, Fathers, Friends and Neighbours, saw in Him a Living Pattern of Their Duties; and ever must remember, the various Excellences of that Heart, the Less of which, They now lament

He Died June 27 1776 Aged 67.

At the time Dr Wall carried out his analysis, the only facilities at the Holy Well were an open spring and a ruined bath, so perhaps it was fortuitous that Edward Popham of The Lodge, near

Improvements to the facilities at the well

In August 1754 Dr Wall published his Experiments and Observations on the Malvern Waters and "The profits of the work to be appropriated...to make the springs commodious".[8]

This gave the Holy Well the medical endorsement it needed for success, and any profit from the sales of his publication was to be used to improve the facilities. The following month an article in Berrows Worcester Journal lamented the fact that, despite being renowned for curing obstinate diseases, the Holy Well wasn't very well used because there was no suitable accommodation for invalids. The article said that a subscription was about be set up to raise some money to solve the problem, but a suitable design was necessary so that the facilities would be available to both the poor and the rich. An undated and unsigned memo in Hereford Record Office describes the difficulty of access to Holy Well and a subscription to set up for two roads and to erect a building with baths, lotion rooms &c., by which the existing reservoir could be filled in. At that time there was no proper road to the well so invalids had to scramble up the steep hill sides. There was no proper bath, no accommodation - not even a cover over the well, which was open to the elements.

To remedy the situation, Two years later "several Noblemen and Gentlemen of this County met ... and subscribed considerable Sums, in order to make the SPRINGS at Malvern more commodious and extensively beneficial - This good Example, we hope, will be follow'd by the Gentlemen of the neighbouring Counties of Gloucester and Hereford; for, as the Sources of these Excellent WATERS are contiguous to the Confines of each, they must, when put in Order, be of particular Service to Them, as well as of general Advantage to the Publick".[9]

To prepare Holy Well for the anticipated rush of invalids, trees had to be planted for shade on the bare hills, zig-zag walks laid out offering beautiful views from the summit, and seats and shelters provided for resting; the Holy Well had to be protected from flooding in the event of heavy rain, and a new access road had to be built between the well and Wells House, a lodging house that was being built nearby.[10] The main promoters were Thomas Berkeley of Spetchley, John Dandridge J.P of Balden's Green[11], Mr Hornyold, lord of the manor of Hanley Castle, Reginald Lygon of Madresfield, and Dr Wall. The Holy Well at Malvern became an 18th century notable spa.

Dr Wall's conclusion, after analysis, that 'the efficacy of this water seems chiefly to arise from its great purity' proved to be a magnet to wealthy invalids.[14] Indeed, in 1747 following his cure of the gout - an ailment ascribed to over-drinking and over-eating - Edward Popham of Tewkesbury erected the first bath house at the Holy Well. Shortly after this time a small hut became available for poor visitors.[15]

The Rev. J Barrett of Colwall, in 1803, notes that the Holy Well was eminently salubrious and of great repute with the ancients. Invalids came from different parts of the Kingdom to experience the waters. Eye complaints, cancers and old ulcers were all within the curing capability of the Holy Well. In addition cutaneous disorders, glandular obstructions and nephritic complaints were successfully resolved. Application was by drinking, lotion and the application of wet sheets.[16] This is an indication that hydrotherapy existed at Holy Well long before Dr Wilson marketed it so successfully in the 1840s. In 1803 a decent building existed for bathing and it was recognised that purity was an essential element in the water curative powers.[17] Southall in the 1820s describes the facilities as consisting of a bath and apartments for different uses of the water. An 1888 article `Principle Drives Around Malvern' notes that Messrs. Burrow were the lessees of the Holy Well Baths.[18]

A further attempt at evaluating the waters of the Holy Well water was published by Saunders in 1805. He noted that when the water was first drawn, it appeared quite clear and pellucid (transparent) and did not become turbid (muddy) on standing. Furthermore it possessed an agreeable pungency when at the table. He noted that the water could be used with utmost freedom, both as an external dressing for sores and as a common drink. Of particular interest are Saunders' 1805 observations that "common people resort to this spring for cutaneous complaints or other sores, who are in the habit of dipping their linen in the water, dressing with it quite wet, and renewing this application as often as it dries".[19] This is the principal of hydrotherapy which was supposedly introduced from Grafenberg by Dr Wilson in the 1840s. Saunders therefore confirms the use of hydrotherapeutic treatment before the generally recognised introduction date by some 35 years or more!

A Guide to all the Watering and Sea-Bathing Places for 1813 says this of the application of Holy Well water - "In cancerous complaints, old ulcers, glandular obstructions, and other complaints for which Malvern water has been prescribed, drinking, lotion, and bathing, according to circumstances, must be used. Early rising, exercise on foot or horseback, with temperance, must be combined with the water; and if the former are regularly pursued and observed, the effects of the latter will be a consequence rather than a cause". Here again is an example of an ancient cure - hydropathy - before it had been labelled, packaged and marketed. Of the facilities offered there the publication continues "The source of the Holy Well is secured by a convenient erection, containing a bath and other accommodations...." and of the patients, "There is a constant succession from Cheltenham, and many other parts of the kingdom, during the summer season".[20]

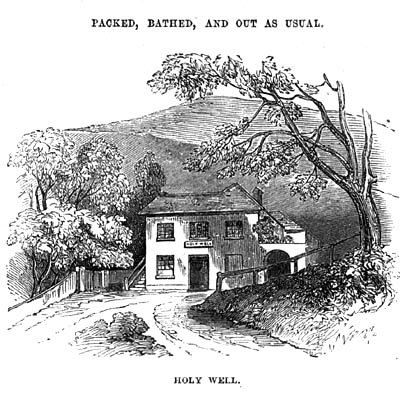

The Holy Well Fount and Building

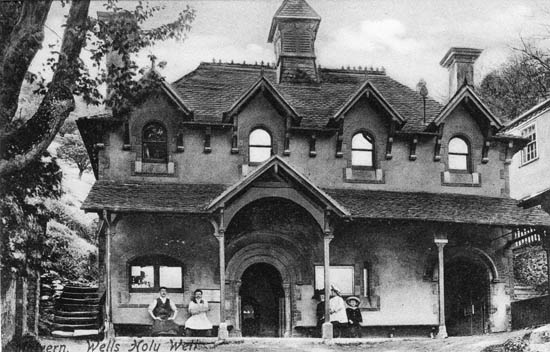

The first reliable illustration of the Holy Well building dates from 1757 and is reproduced in Weaver C (2015) The Holy Well at Malvern Wells. An illustration by Lane dated 1845 shows a modified version of this original building. It was again extensively modified mid 19th century by adding a first floor extension on the right hand side, four gables, modified doors and windows, a veranda and a turret on the roof. This adaption of the earlier building heralded the take over of bottling at the time by Schweppes. In 1843 Lord of the Manor Thomas Charles Hornyold bought back the well and for 400 pounds restyled the well house with baths at the back of the well room c.1846. It was refashioned in the distinctive cottage orni style, which is contrived by adding decorative features to country cottages to make them more rustic and picturesque. John Parkes, former proprietor of the Holy Well, suggested that the style was chosen by architects who visited

At the beginning of the 19th century William Steers was the proprietor of both the Rock-house and the Wells House near the Holy Well and it was noted that Mary Steers "at a great personal expense, preserved to Malvern people the use of the Holy Well".[22] Further details reveal that "Some time in the "forties" of the last century the landlady of the Rock House, near the spring, undertook a very expensive course of litigation against a neighbour who was arranging to make the flow of water private property for himself, but he was defeated, and an injunction was provided that always the public should have free access to the water; to the great credit of Miss Stears".[23]

Just a few years later the public once again almost lost their access to the water. In 1875 Mr S.Ballard constructed a tank in the

The Holy Well site was once part of the Hornyold estate. In 1919 it was sold as

By the 1970s the Holy Well had become so dilapidated that once again its survival was dependent upon a private benefactor. By then the Holy Well building was listed as Grade II and of Architectural Interest. In 1974 the owner, Mr John Parkes, undertook extensive restoration and renovation costing approximately 15,000 pounds in conjunction with the Civic Trust - see below. This included 120 pounds for laying on mains water - 80 years earlier Cuff's had applied unsuccessfully for mains water for bottle-washing - and spent 60 pounds to 'Excavate for and determine

the route of water line from well to fountain room'.[25] During restoration the upper windows were extended downwards, the porch at the front having been removed earlier in the 1930s. Even more recently the Humms have renovated the building and converted it to residential accommodation.

the route of water line from well to fountain room'.[25] During restoration the upper windows were extended downwards, the porch at the front having been removed earlier in the 1930s. Even more recently the Humms have renovated the building and converted it to residential accommodation.

Bottling at the Holy Well

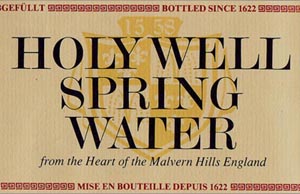

The Holy Well water is said to have been bottled and exported since at least 1622, when a song records how it was widely distributed from Berwick to

A Thousand Bottles there

Were filled weekly,

And many Costrils rare

For stomachs sickly;

Some of them into

Some of them to

Others to Berwick went,

O Praise the Lord!

There are few known 18th-century references to bottling, but in the early 19th century servants and carriers frequently bottled and exported the water. Henry Biggs of Castlemorton remembered that it was about 1808 when he worked for eight months for Mrs Barry of

Source water bottling as a business is only viable at a reliable source. Such a source must have adequate volume, be free from harmful contamination and have an acceptable mineralisation. As technology and science has advanced over the years, the requirements for bottled source waters have similarly become more stringent. Originally the Holy Well source was a streamlet from a pond at the head of the valley. This pond is illustrated in picture 4. The accumulated water appears to have come from a combination of groundwater and near surface seepage as well as a geological fault running east/west which provides a common aquifer with Moorals Well on the western side of the hills. At some point in the mid 19th century the pond was contained, and the supply taken underground to the Holy Well house.

Although purity was previously ascribed to the waters, the new techniques of chemistry achieved by 1822 started to cast doubt on the original assumptions and it was appreciated that Holy Well water did contain minerals. The Malvern Guide of 1822 enters into a long debate assessing the active ingredients of the waters but the results are inconclusive due to the crude state of scientific knowledge at the time.[26] Much of this debate had previously been published by Chambers in 1817, including the Philip's analysis.

Later Granville published an analysis of Holy Well water, comparing it with other English waters. Chemistry was not a developed science in those days and it is only later that reliable chemical evaluations became available. The integrity of the Holy Well was challenged by Dr Granville in the 1840s when he voiced the opinion that it was a contained streamlet rather than a spring.[27] It was possibly this, coupled with the further development of hydrotherapy, resulted in the emphasis moving away from Malvern Wells to Great Malvern.

That the Holy Well is a reliable source is confirmed by the following quotation dated 1906. "But if the word Holy in connection with the Well has lost all its supernatural meaning, the marvellous purity of the water remains, and - what is very important in days of water scares - it still issues from the Hill in undiminished quantity and no drought, however lengthened, makes any appreciable difference in the flow".[28]

The Holy Well water has supposedly been bottled since 1622 according to Smith, although Hembry gives a date of 1760 (p.366), but bottling ceased in the 1990s. Schweppes started exploiting Holy Well water for bottling in 1850s. They launched Malvern Soda Water at the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was initially produced at the Lea and Perrins bottling works in Malvern but production was transferred to the Holy Well in 1856. (see 121 Bottling Works Spring) This was the start of 160 years of bottling Malvern Waters under this brand. This great logevity came to an end with the closure of the Colwall plant in 2010. Schweppes had sub-leased the rights for Holy Well water from W & J Burrow of Malvern. This arrangement continued until the early 1890s when Schweppes built their Colwall bottling plant and used the Glenwood Spring water supplied by Ballards.

Burrows bottled Malvern Waters both from here and

Cuff's business started in Manchester in 1801, later moving south, for in 1895 Messrs John & Henry Cuff took a long lease on the Holy Well spring and the end of the 19th centry.[29] Being the sole lessees they made extensive alterations and improvements and new machinery was installed by mineral water engineers Messrs Hayward Tyler & Co. of London. The water emerged from the source near the works at approximately 3 gallons per minute, and flowed directly into the factory. No pipes or conduits were used so there was no contact with iron or lead piping and the machinery used was coated with tin to avoid contamination.[30] Cuffs continued bottling at their mineral water factory here until the 1950s, using the building in front of and to the right of the Holy Well building. Codds and Hamilton bottles act as residual reminders of this enterprise.

In 1904 Ingram and Royal published their eleventh edition of "Natural Mineral Waters: their properties and uses" in which they point out that the most active and trustworthy Malvern Waters are those from higher altitudes. Springing from the "Syenitic" rocks at an altitude of 756 feet, such waters are distinguishable because they bear the Alpha label. Lea and Perrins (better known for their Worcester Sauce) were soda water manufacturers as early as 1851. Burrows then merged with them and produced the `Alpha Brand' natural water from St Ann's Well, selling this product well into the 20th century.[31]

Like St Ann's Well, Holy Well is of low mineral content, clear and pleasant to taste. A quantitative analysis carried out by Mr Alfred Mander at the Belle Vue Pharmacy in 1895 [32] provides confirmation of the purity. By the 1880s the water was still being perceived as of high purity although recognised as containing low quantities of minerals.[33]

Originally the Holy Well was one of the most famous of Malvern's sources but times changed and a 19th century article on Malvern's waters describes it as being `almost as famous as St Ann's'.[34] Today the water can be sampled in the historic Holy Well building from the spout that incorporates the original cruciform channel design purported to have dated from the original 17th century installation, albeit replaced from black limestone to white marble..

The Decline and Recovery of the Holy Well

In 1919 Blackmore Park Estate was put up for sale.

It may have been through lack of investment and sales during the Second World War, but in 1946 there was a complaint that the Holy Well was in a neglected state and there was no water for the public. Ten years a later a visitor from Hove, who had come to recapture some of the Holy Well's old charm, disappointedly complained that the beautiful view had been blotted out by trees and the building was dilapidated and filled with old packing cases. In 1957 the owner offered to sell the Holy Well, with all its land, buildings and water rights, to the Malvern Hills Conservators for 10,000 pounds. The MHC really only wanted the land, and offered 1,000 pounds. Their offer was rejected. Throughout the 1960s the Holy Well deteriorated and was described as being in poor condition and very tatty and by 1970 the Holy Well and the adjacent cottages - Rock House and Bath Cottage - became completely derelict.

Although the Holy Well building was listed as Grade II and of Architectural Interest, it was so dilapidated that its survival depended upon a private benefactor. Fortunately, in May 1972 John Parkes of Penylan,

When John Parkes retired, the Holy Well was bought by Marion and Mike Humm. At the beginning of the 21st century they delightfully, tastefully and sensitively renovated and modernised the upper rooms for tourist accommodation. Further restoration took place in the new millennium with the aid of Heritage Lottery/matched funding, and in December 2009 a visitor centre opened that gives a fascinating account of the surprising water heritage of the

When John Parkes retired, the Holy Well was bought by Marion and Mike Humm. At the beginning of the 21st century they delightfully, tastefully and sensitively renovated and modernised the upper rooms for tourist accommodation. Further restoration took place in the new millennium with the aid of Heritage Lottery/matched funding, and in December 2009 a visitor centre opened that gives a fascinating account of the surprising water heritage of the

In the year 2001, hydrogeologists John Findlay and Anna Jeary of Zenisth International, carried out a review of the existing water source and made recommendations for the future. The report was arranged by Dr Bruce Osborne and was part of the matched funding for the Heritage Lottery Funding bid being orchestrated at the time. This report advocated a number of measures to overcome the unreliability of the water supply. There then followed a period of renovation of the infrastructure with the result that a new venture in 2009 was the advent of a bottling enterprise, once again returning to the tradition of Holy Well water being available far and wide.[35] The present day bottling plant includes a water heritage centre on the ground floor in conjunction with the sacred spring which is freely available to visitors.

In 2012 The Humm family, who bottle at the Holy Well decided to add Malvern to their label branding. Since the closure of Schweppes Malvern Water bottling works at Colwall, the name Malvern has not appeared on bottled water and so this was an opportunity to reinstate a tradition that dated from 1851 when Schweppes bottled for the Great Exhibition.

1. Picture of early building from Lane R J. 1855 A Month at Malvern, p.66.

2. The modern day bottling plant.

3. Mrs and Mr Cuff, bottlers of Holy Well water

4. The pond at the valley head - mid 19th century painting. This is the site of the spring and was subsequently contained underground.

5. Dr Wall's comparison with other waters, in his own hand.

6. Tourist visitors to the Holy Well. The 56 seater Malvernian coach arrives at Holy Well on the celebrated annual conducted tour of the springs and wells in 1999. (courtesy Lynda Thatcher) Afterwards the road was banned to coaches.

7. The Holy Well building 2011

8. The van prepares to deliver Holy Well waters 2012.

9. Holy Well building about 1900.

10. 1980s label.

11. Bottles displaying the Malvern name in 2012.

12. Modern day bottling at Holy Well.

[1] Berrows Worcester Journal, 7 Oct 1756 [2] Malvern Gazette, 22nd July 1904.

[3] W. Wickham, Malvern Field Club 1904 'Springs and Wells in the locality of Malvern' in Kelly's Directory of Malvern and Neighbourhood, 1950.

[4] Osborne B. Weaver C. Aquae Britannia (1996) Cora Weaver, Malvern. p.211.

[5] Short T. History of the Principal Mineral Waters, 2nd ed. (1740) BL 34d16, p.88.

[6] Andrews Map, 1797 author, ex libris.

[7] Smith, 1964 p.175.

[8] Chambers 1817 p.281.

[9] Berrows Worcester Journal, 7 Oct 1756.

[10]HRO G2/670.

[11]Barnards Green.

[12] Reference - Worcestershire Summer Assizes 1838, in the Exchequer of Pleas, Steers v. Carwardine.

[13]The Malvern Gazette, 10 June 1904

[14] Smith 1964 p.175.

[15] Hembry p.251.

[16] Barrett 1803 p.31-35.

[17] Barrett 1803 p.34-36.

[18] Malvern Advertiser, 8 Sept 1888.

[19] Saunders 1805 p.100-107.

[20] A Guide to all the Watering and Sea-Bathing Places. 1813. p.296/7.

[21] Kelly's Directory of Malvern and Neighbourhood, 1950.

[22] Malvern Advertiser 18 May 1895.

[23] Malvern Gazette 11 Nov 1904.

[24] Malvern Gazette 11 Nov 1904.

[25] HWRO ref.471.02 BA 8821/25.

[26] Malvern Guide 1822 p.13-24.

[27] Granville 1841 p.268.

[28] Malvern Gazette 26 May 1906.

[26] Kelly's Directory of Malvern and Neighbourhood, 1950.

[29] Malvern Advertiser, 15 July 1899.

[30] Malvern Gazette, 26 May 1905.

[31] Kelly s Directory 1942.

[32] Malvern Guardian January 1895 p.15.

[33] May. c.1880, p.140/1.

[34] Malvern Advertiser 2 July 1881.

[35] Zenith International Ltd. (2001) Holy Well, Malvern.

Website: Click Here

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Celebrated Springs of

THE MALVERN HILLS

A definitive work that is the culmination of 20 years researching the springs and wells of the Malvern Hills, published by Phillimore. This is the ideal explorers guide enabling the reader to discover the location and often the astounding and long forgotten history of over 130 celebrated springs and wells sites around the Malvern Hills. The book is hard back with dust cover, large quarto size with lavish illustrations and extended text. Celebrated Springs contains about 200 illustrations and well researched text over a similar number of pages, together with seven area maps to guide the explorer to the locations around the Malvern Hills. It also includes details on the long history of bottling water in the Malvern Hills.

A definitive work that is the culmination of 20 years researching the springs and wells of the Malvern Hills, published by Phillimore. This is the ideal explorers guide enabling the reader to discover the location and often the astounding and long forgotten history of over 130 celebrated springs and wells sites around the Malvern Hills. The book is hard back with dust cover, large quarto size with lavish illustrations and extended text. Celebrated Springs contains about 200 illustrations and well researched text over a similar number of pages, together with seven area maps to guide the explorer to the locations around the Malvern Hills. It also includes details on the long history of bottling water in the Malvern Hills.

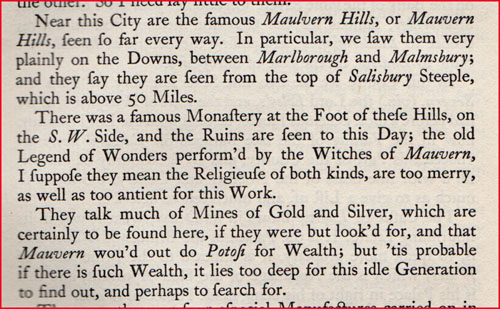

FOOTNOTE: As mentioned earlier, records detailing the Holy Well go back to the 17th century although the spring is likely to have been important during medieval times. In the eighteenth century Daniel Defoe, in his book "Tour thro the Whole of Great Britain (1724-7), mentioned the Witches of the Malvern Hills (see text below left). This could be seen as a reference to the Holy Well for healing before formal medical practice recognised the benefits of the water. Informal healing was carried out by wise women of the local populace using a variety of folk practices and magic. Sometimes these practices were perceived as evil, particularly when they were directed at mental illness and psychological conditions. These women became labelled witches and capable of both good and bad. The tradition of witchcraft likely perpetuated from medieval times at Holy Well. The following appeared on Facebook in July 2020:

"In England the Witch Act was repealed in 1736 stopping all legal persecutions for sorcery and witchcraft. In spite of this, persecution of supposed witches continued. In 1783 a particularly ugly woman was nearly drowned in the vicinity of Worcester upon the supposition of practicing witchcraft. William Lygon, a County Justice who lived at Madresfield Court Malvern, intervened in the ducking of the accused. He was later made the first Earl Beauchamp. Even today there are fears of witchcraft in the Malvern Hills. There is a tradition of leaving flowers, holy symbols and prayers at the Holy Well as symbolic offerings of thanks for the healing waters of the Holy Well. There are also rumours of sinister dark practices at the public fountain. Evidence of such practices have left the owners removing much of the evidence leaving the annual well decorating the only formal opportunity for such display."

1) TOPOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:

Malvern Hills - arguably Britain's original National Park

2) LANDSCAPE:

Uplands3) INFORMATION CATEGORY:

A Spring, Spout, Fountain or Holy Well Site4) MALVERN SPRING OR WELL SITE DETAILS:

Site with Malvern Water5 SPLASHES - Prime 'Must See' Site

Water Bottling - Past or Present

Water Bottling - Past or Present5) GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION:

Access By RoadAccess On Foot

Free Public Access

Free Parking Nearby

Accessible All Year

Popular Water Collection Point