The following investigation was prompted by research into the springs and wells linked with the Purlieu Brook, near the Wyche Cutting on the Malvern Hills.

As early as Elizabethan times there was believed rich mineral wealth to be had in the

Malvern Hills. The first mining charter was apparently granted by Elizabeth I. At the time the Crown sought to maintain a monopoly on mineral exploitation and in granting a charter, Elizabeth undertook to ensure that only those with the royal approval could extract minerals. "The Queen promised to disturb all persons doing anything contrary to the privilege". This included the "overthrowing of engines and buildings". The recipients of the charter however had a cost to pay in the form of one tenth of gold, silver and quick silver found native, and of ores containing over 8lb. of fine gold or silver in the cwt. In addition the Queen was to have a right of purchase before others, on the remaining gold or silver, paying market price less eight pence an ounce for gold and less one penny an ounce for silver. (1)

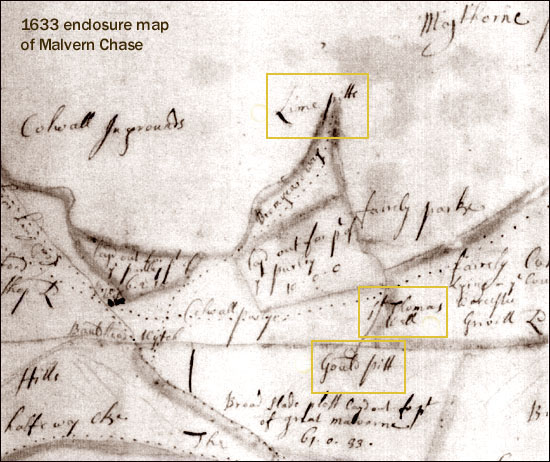

The 1633 enclosure map of Malvern Chase shows a spring rising at 'The Gould Pitt' (now known as The Gold Mine, 350m north of the Wyche Cutting), and its stream running west past St Thomas's Well, where the Royal Malvern brewery and bottling works was later built, and down the Purlieu. The above is the earliest documentary evidence of gold mining in the Malverns that this author has so far come across.

Map above - the 1633 enclosure map showing the Lime Pitts at the lower end of the Purlieu, St Thomas's Well, where later the West Malvern Spa would be built and the Gould Pitt; the map is orientated with west at the top, north to the right.

Between 1711 and 1721, a William Williams of Bristol and a Doctor Dudley spent 600 pounds initially working from a level or horizontal passage of 240 feet and then sinking a deep shaft of 220 feet to find metallic ores in the Malvern Hills. A detailed account of this adventure appears in Chambers J "A General History of Malvern" (1817) Ch.VIII. In the account it refers to local people calling the scales of mica "gold dust", also the bronze lustre of micareous substance  within the rocks being called "cat gold" in the Malvern hills. To read this account in full, click on Chambers Mineralogy left.

within the rocks being called "cat gold" in the Malvern hills. To read this account in full, click on Chambers Mineralogy left.

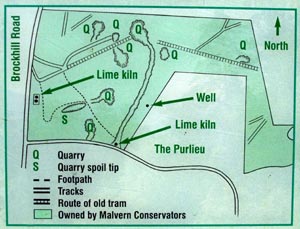

Daniel Defoe between 1724-7 had noted a gold mine a little north of the Wyche cutting, by then abandoned. He commented 'they talk much of Mines of Gold and Silver, which are certainly to be found here....' He observed that if there was such wealth it was likely 'it lies too deep for this idle generation to find'. Were these early prospectors deceived by the glittering mica in the rocks? The belief of gold in the

Malvern Hills was supposedly disproved in the 19th century; albeit the rumour of gold being found in small quantities perpetuates.

Charles Hastings M. D. in his Natural History of Worcestershire (1834), on page 89, refers to the Gold Mine as follows:

It is indeed, but a few years ago, so complete was the ignorance of persons upon these subjects, that a shaft was sunk to raise gold from the hills of Malvern, and the individuals concerned lost a large property in speculation.

The spot where these mining transactions were carried out is still called "the gold mine" by the country people; but whether in reality the proprietors of this scheme thought that gold could be found there, or were merely in search of copper or tin ore, traces of which it is said they discovered, certain it is that after carrying out their operations for some years to no good purpose, the scheme was abandoned. Geology not being well understood in those days, it is probable that the splendid lustre of micaceous rock which abounds at this point, misled them as to its metallic composition

During the 20th century technology advanced and it was possible to take a more scientific approach to the possibility of gold in the Malvern Hills. In the mid 1930s, two researchers Brammall A. and Dowie D L. at Imperial College, London carried out a detailed evaluation of a wide range of Malvern rocks and determined that gold did after all exist in the hills. They concluded that the higher occurrences were in the red granites and red granite pegmatities and derivatives of these rocks. The published paper can be read by clicking Website below. Later research for an unpublished PhD thesis by D W Bullard of University of Nottingham in 1975 was unable to verify the results of Brammall and Dowie. None of the 37 Malvern granites that Bullard analysed contained detectable quantities of gold. This suggests that the gold is elusive to say the least. (2)

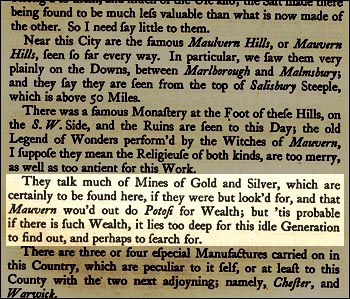

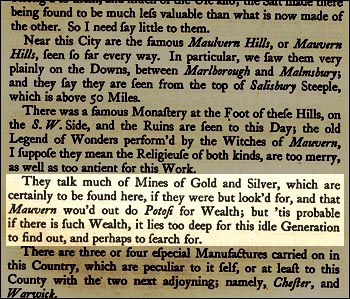

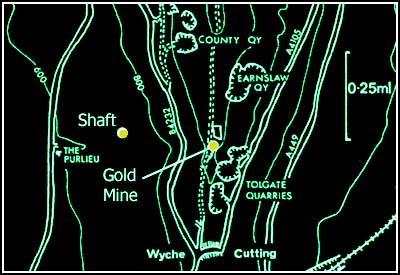

Now the story has a 21st century twist. In our exploration of the springs and wells for Celebrated Springs of the Malvern Hills we noted what is generally described as a "well" shaft in the woods on the northern side of the Purlieu. The sequencing picture above shows the shaft near the Limekilns. The logic for digging a well at this point does not stand up to scrutiny because there is much more easily obtainable water nearby. Comparison with other similar sites elsewhere suggests that the shaft is possibly an old mine, with the once buried covering now rotted and collapsed.  The working quarry face for the limestone is nearby and the shaft may well have been rediscovered as the face moved west. It was then covered in timber and other materials of more recent origin and buried beneath the spoil that the quarry workers threw behind them as the face advanced. The Malvern Hills Conservators map showing the "Well" is reproduced right.

The working quarry face for the limestone is nearby and the shaft may well have been rediscovered as the face moved west. It was then covered in timber and other materials of more recent origin and buried beneath the spoil that the quarry workers threw behind them as the face advanced. The Malvern Hills Conservators map showing the "Well" is reproduced right.

The proximity to the legendary gold workings prompts the hypothesis that this may be a shaft down to the 18th century gold mine. This idea is supported by gold mining practice of that time. Following an assay to determine whether a mine might be profitable, it was practice to first dig a shaft, into which were installed pumps, ladders and a lifting gear. From the lower part of the shaft, a horizontal drift or level might be dug and at a suitable spot a further shaft sunk from the level to reach deeper deposits. In order to ensure air circulation a second surface shaft was dug down to the drift or level, at the furthest point from the first surface shaft, to provide ventilation. If the two surface shafts were of different height the air circulated freely, as would be the case of the Malvern gold mine. If not a fire would be lit at the foot of one shaft to provide an updraft. (3) It would appear therefore that what is described as a "well" is possibly a shaft linked to the original gold mine. Alternatively it may have been dug to access limestone beds inaccessible from the surface workings, or linked with an aborted reservoir scheme of the early 20th century. Perhaps an archaeological exploration might be launched to resolve this mystery?

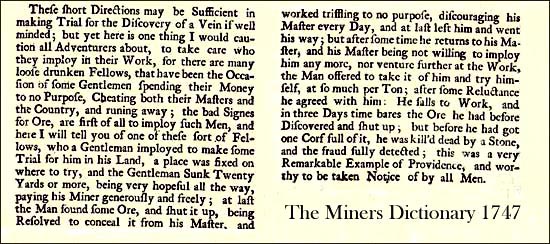

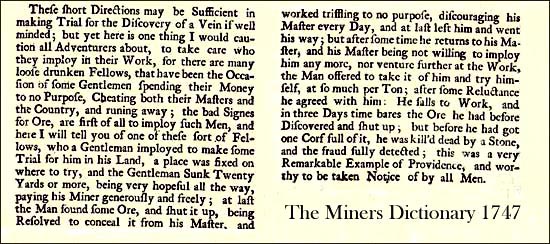

However even if the 'well' links to mine workings, would an exploratory expedition expect to find gold ore in the Malvern Hills mine? If we are to believe authors like Hastings above, the answer would be no. The proprietors of the mine apparently found nothing of good purpose. However the following text panel cites a warning to adventurers about those they employ. In the example the employed miner concealed from the mine proprietor the discovery of gold, only to later mine it under his own initiative. In this instance fate took revenge and the cheat was killed by a falling stone. Was this the case in Malvern? Perhaps gold was discovered and the strike kept secret, for whatever purpose. This example was taken from a 1747 book published only twenty six years after the Malvern venture. (4)

The question arises therefore is there winnable gold in the

Malvern Hills? The British Geological Survey's MineralsUK, Mineral Reconnaissance Programme report 144 (1997) page 40, identifies alluvial gold in the Malvern Hills suggesting a water eroded higher deposit. A concrete structure in the Purlieu stream near the shaft on the Conservators map above could be interpreted as a settling tank. The Purlieu stream coursed through the structure and alluvial gravel was collected on the floor of the stucture for later separation. There is also the real possibility that the Purlieu stream is fed by a drainage adit from the gold mine as well as St Thomas's Well, or maybe they are now both one and the same?

During the days of the gold rushes, both in the

United States and in

Australia, the last thing you did was tell anyone when you struck gold. Not only did it attract speculative prospectors, it also attracted thieves, rogues and vagabonds all out to cash in on easy pickings, not to mention the opium dens and bordellos. Also in the case of Malvern, the lord of the manor or the Crown may demand the mineral rights dues.  Over the last 300 years, was

West Malvern on the verge of becoming a gold rush town? Only the dispelling of the belief or perhaps a wall of silence, concerning possible gold deposits prompted future economic activity to be focussed on other commercial enterprises such as Malvern Waters and the Water Cure and of course general stone quarrying.

Over the last 300 years, was

West Malvern on the verge of becoming a gold rush town? Only the dispelling of the belief or perhaps a wall of silence, concerning possible gold deposits prompted future economic activity to be focussed on other commercial enterprises such as Malvern Waters and the Water Cure and of course general stone quarrying.

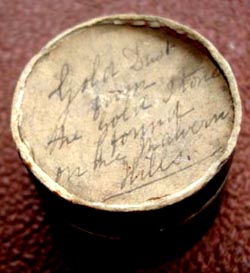

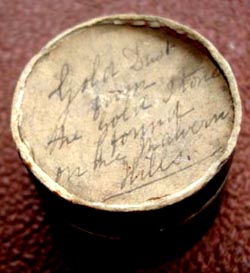

There has understandably been a lack of hard evidence over the centuries about the existence of Malvern gold; that is up until now. Pursuing investigations further we have now actually acquired samples of supposedly natural Malvern gold dating from the 19th century. These samples are being investigated further together with recent rock samples gathered from the vicinity of the Gold Mine spoil heaps. This new evidence will be vital

in establishing the credibility of the legend of gold in them thar 'ills.

Click Website below for details of "The distribution of gold and silver in the crystaline rocks of the Malvern Hills" (1934) Brammall A., Dowie D L., Imperial College, London.

GOLD MINE - NEW EVIDENCE

GOLD MINE - NEW EVIDENCE

within the rocks being called "cat gold" in the Malvern hills. To read this account in full, click on Chambers Mineralogy left.

within the rocks being called "cat gold" in the Malvern hills. To read this account in full, click on Chambers Mineralogy left.

The working quarry face for the limestone is nearby and the shaft may well have been rediscovered as the face moved west. It was then covered in timber and other materials of more recent origin and buried beneath the spoil that the quarry workers threw behind them as the face advanced. The Malvern Hills Conservators map showing the "Well" is reproduced right.

The working quarry face for the limestone is nearby and the shaft may well have been rediscovered as the face moved west. It was then covered in timber and other materials of more recent origin and buried beneath the spoil that the quarry workers threw behind them as the face advanced. The Malvern Hills Conservators map showing the "Well" is reproduced right.

Over the last 300 years, was

Over the last 300 years, was

A definitive work that is the culmination of 20 years researching the springs and wells of the Malvern Hills, published by Phillimore. This is the ideal explorers guide enabling the reader to discover the location and often the astounding and long forgotten history of over 130 celebrated springs and wells sites around the Malvern Hills. The book is hard back with dust cover, large quarto size with lavish illustrations and extended text. Celebrated Springs contains about 200 illustrations and well researched text over a similar number of pages, together with seven area maps to guide the explorer to the locations around the Malvern Hills. It also includes details on the long history of bottling water in the Malvern Hills.

A definitive work that is the culmination of 20 years researching the springs and wells of the Malvern Hills, published by Phillimore. This is the ideal explorers guide enabling the reader to discover the location and often the astounding and long forgotten history of over 130 celebrated springs and wells sites around the Malvern Hills. The book is hard back with dust cover, large quarto size with lavish illustrations and extended text. Celebrated Springs contains about 200 illustrations and well researched text over a similar number of pages, together with seven area maps to guide the explorer to the locations around the Malvern Hills. It also includes details on the long history of bottling water in the Malvern Hills.